In search of boxer's hidden instinct, from within his inner sanctum

- Published

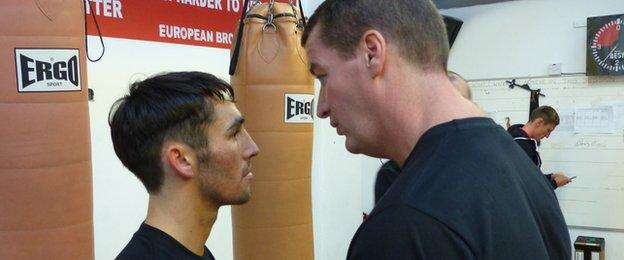

Jamie Conlan after his win over Junior Granados

Watch prize fighting and the feats or flaws you witness might seem exclusively physical at root. But at the elite level of boxing, where athletic excellence and intense dedication are a given - or at least should be, internal factors are often what differentiate the combatants. On Saturday in Dublin, Paul Gibson went in search of a fighter's hidden instinct.

In about eight hours' time, Jamie Conlan will be in the midst of a savage physical confrontation.

Right now, he is sitting in the lobby of a Dublin hotel answering the same question from every passer-by who pauses to wish him luck. Camp went perfectly and he's feeling great is his standard reply. What else is there to say?

"I look about and see people going to work or about their daily life and it's funny to think that they have no idea what I'm about to put myself through," says Conlan, a super-flyweight from Belfast with 13 professional wins to his name.

This is one of many little insights Conlan allows me as his fight approaches. Outwardly at least, he appears calm, without a hint of the nervous energy I expected to encounter in a boxer this close to the climax of two months' intense preparation. Conlan is headlining a televised show in his first fight with a new trainer after nine months' inactivity.

"I've prepared so well that my mind is clear," says Conlan. "I'm ready and I know I'm going to win." He smiles sheepishly before adding: "But every now and again, even as I am thinking like that, a little 'what if' appears." Such honesty seems like a sign that Conlan is mentally positioned on the right side between confidence and complacency.

"I'm ready and I know I'm going to win. But every now and again, a little 'what if' appears."

Unsure whether to press Conlan about what lies ahead, we dance between different topics, only occasionally drifting back to boxing. At times I wonder if he is thinking about the fight at all.

"It comes and goes," says Conlan. Apparently, it is still early to be fully focused on the serious business of hitting and being hit.

Three hours later we are in a taxi together, making the short journey along the canal to Dublin's National Stadium. As we arrive, heavyweight Sean Turner - who goes by the nickname Big Sexy - marches past us on his way to the ring. The changing area is a hive of activity, with undercard fighters hitting pads, wrapping hands, shadow boxing and plotting with trainers.

It's a jovial atmosphere but as news of comfortable home wins filters through from the arena, Conlan remarks he may be the only guy who will be given a real fight tonight. Nobody who heard those words had any idea how prophetic they would prove to be.

As others prepare, fight, win, shower and leave, the mood gradually changes in Conlan's camp. As Conlan sits and listens to instructions from his trainer Danny Vaughan and his hands are wrapped by Danny's father George, he gives me a pre-arranged nod to indicate the butterflies in his stomach have awoken from their slumber.

Referee Mickey Vann calls in to give the standard instructions before the gloves arrive and are suitably roughed up before Conlan tries them on. Conlan works the pads with Danny but something seems wrong.

The wrapping of a fighter's hands is one of boxing's most sacred rituals and a privilege to witness

His father, John, high performance director of the famed Irish amateurs, offers a chair and a quiet word and it looks like a private prayer is being whispered to the wall. Jamie's stomach isn't right, a mistimed final meal or the irritable effects of stress and nerves the most likely culprits.

An official indicates 10 minutes until show time and suddenly Conlan's dressing room feels like a movie set. Two weeks ago, at his training camp in Marbella, Conlan revealed that this is the part of boxing that he hates the most and knows he'll miss the most - a most illuminating contradiction.

There are no histrionics. No punching walls or exaggerated yelps of encouragement. Vaughan, like John Conlan before him, is a calming presence. Jamie never has and never will fight angry.

There are words and nods from the other pros still milling about but, one by one, they slip away to the cauldron next door. Each departure accentuates the loneliness of Conlan's situation.

We all rise for the ring walk. Every other Irishman on the bill has won. Another millibar of pressure added. The curtain parts, allowing a flood of noise and light to wash over us. Jamie, at the front, bears the brunt. Suddenly, The Irish Rover strikes up to signal his imminent arrival.

I take my seat at ringside along with the great and good of Irish boxing. It is time to see the effects of the new regime: the impact of morning sprints under a Spanish sun, the green tea and poached egg diet, the saunas and steam rooms and plunge pools, the nine weeks away from family and friends.

Conlan receives his final instructions from trainer Danny Vaughan - before wading into battle

The fight needs many more words than I have to do it justice. The first three rounds are cagey before Junior Granados, a toughie from Mexico, serves notice of his power by buzzing Conlan in the fourth. Jamie wins the next two before a truly torrid seventh for the Irishman, in which a sickening body shot leaves him and the crowd gasping for breath.

Down on his hands and knees, Conlan bites hard into his gum shield and beats the canvas floor in a mixture of agony, frustration and defiance. He rises at nine and bobs and weaves for dear life as Granados unloads with everything - 63 unanswered punches according to some sources.

Throughout the fusillade, Vann remains poised to step in. But he never does. Conlan later tells me he was praying that Granados did not go back to his body. That might have been the end.

Finally spinning off the ropes, Conlan is caught and goes down again. It is the dying embers of the round but, upon rising once more and hearing the bell toll, he traipses to his corner looking for all the world a beaten man. The crowd isn't having that, however.

Stories of fans constituting an extra man are a penny a dozen in sport but on this occasion the crowd's influence is undeniable. They roar themselves hoarse. Conlan speaks later of shivers running down his spine and tears welling in his eyes. There follows an eighth-round revival that makes Rocky Balboa comebacks appear understated before clinching a unanimous decision.

I expect euphoria back in the changing area but the overriding emotion is more disbelief and admiration. Young fans, press and fellow pros jostle each other to secure a photo with the champ. The doctor takes a careful look and despite a bloody nose and grossly swollen right eye and top lip, there is nothing broken. Four stitches will suffice.

With his victory over Granados, Conlan improved to 14 wins and no defeats as a professional

Back in the hotel the broadcasting team rise to greet Conlan and he is presented with an unofficial fight of the year award. "There won't be a better fight this year," someone declares confidently. There might not be better fight for years.

Conlan and I share a lift up to his hotel room with Granados's trainer. He tells me he can't believe what Conlan has just done. He mentions heart and gestures to another part of the body that is universally recognised as representing bravery above and beyond the call of duty.

We get out on the seventh floor, where Jamie's girlfriend Tracey is waiting. She hates watching him fight but finds it preferable to sitting at home waiting for a phone call. She always asks not to be seated too close to the action, so knowing she was placed ringside for the bloodiest battle of her boyfriend's professional career, I expect an emotional wreck.

When the door opens, I see love and pride. All she wants to do is hold her man. Suddenly, my interest feels voyeuristic.

Meanwhile, a message arrives from Conlan's brother Michael, the current golden boy of Irish amateur boxing: it is a combination of respect, admonition and a physical threat to never put him through that again.

Conlan is subdued now, preoccupied by the negatives of his performance and mistakenly interpreting his father's concern as disappointment. Technically, he was off. But I feel compelled to tell him he showed the world something else, something that can never be taught in the gym.

"Was it really that good?" Conlan asks innocently. He genuinely has no idea what he has just done.

- Published6 July 2015

- Published6 July 2015

- Published6 July 2015

- Published11 June 2018