Tyson Fury: Ex-champion needs help with drug & mental health problems before return

- Published

Tyson Fury's turbulent 12 months

For a man often described as capricious, Tyson Fury's chaotic reign as world heavyweight champion was strangely predictable.

Since dethroning Wladimir Klitschko in Dusseldorf last November, the Briton has resembled a runaway lorry - smashing through road blocks and red lights, skittling well-meaning people frantically waving warning flags, and only slowing down to shout obscenities and honk his horn, the louder the better.

But that can happen when your mind is scrambled and you don't know what's what: you might be in the driver's seat but your hands aren't on the wheel, your feet are up on the dashboard and there's a brick on the accelerator pedal.

Another way of looking at it is that Fury's crash actually came on that fateful night in Germany and he has been spewing smoke ever since. The morning after the Englishman's stunning upset of Klitschko and his acquisition of the WBA, IBF and WBO belts, he admitted he might struggle to cope.

But not even those closest to him could have anticipated how true that would prove. Having beaten the various boxing authorities to the punch and relinquished the belts before being banned, stripped or both, it's anyone's guess as to when - if ever - he'll have his keys back and his engine revving again.

An all-action man with stifling mental struggles

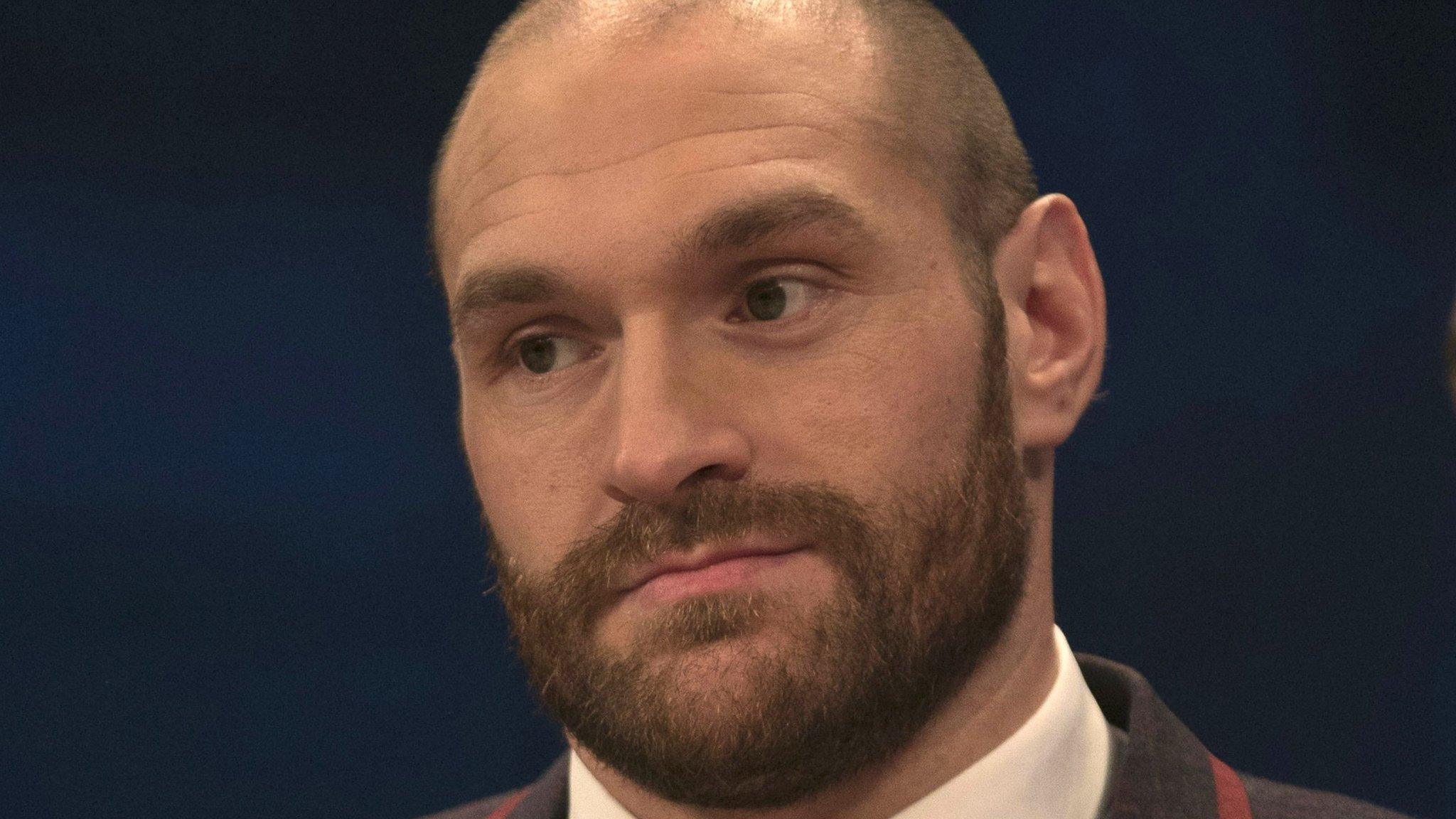

Fury has been speaking about his mental health struggles for years, with disarming and often alarming frankness. So his pronouncement immediately after his victory over Klitschko and the recent news that he was withdrawing from the scheduled rematch because of depression was not a shock.

When I interviewed him in 2013, he described himself as "an all-action man in anything I do. If I'm drinking, I'm drinking until I can't stand up. If I'm going out for Chinese, I'm going to an all-you-can-eat Chinese. If I'm eating cake, I'm eating the whole cake. I don't know what you'd call me. An idiot, maybe?"

Hardly surprising, then, that having fulfilled his dream of winning the world heavyweight crown, Fury would lose focus. Most people having fallen down drunk or eaten a whole cake would steer clear of booze and Battenbergs for a while. But Fury is not most people.

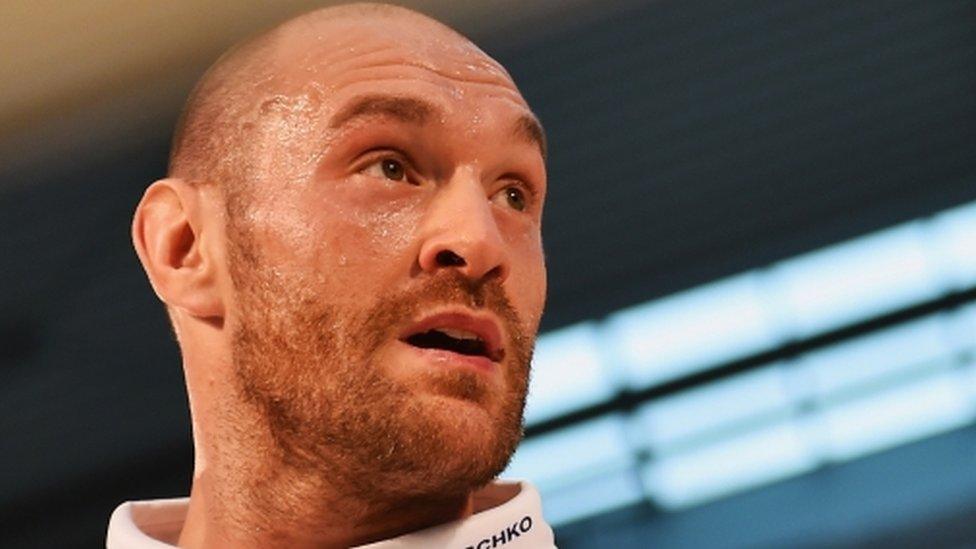

Tyson Fury beat Wladimir Klitschko by unanimous decision in Dusseldorf last November to win the WBA, WBO and IBF world heavyweight titles

Fury is not the first boxer to lose motivation having reached the pinnacle of the sport, and he certainly won't be the last. Not many people climb Everest twice.

After pulling off one of the greatest shocks in sporting history by beating the seemingly invincible Mike Tyson in 1990, Buster Douglas didn't train much, got fat and lost the world heavyweight crown to Evander Holyfield in his first defence. The American promptly retired, almost doubled in weight, then nearly died after falling into a diabetic coma before being struck down by depression. Same old, same old.

Jess Willard's victory over the great Jack Johnson in 1915 was almost as unbelievable as Douglas's upset of Tyson, and his reign even more shameful. Willard clearly didn't fancy fighting much, defending the world heavyweight crown once in four years before being bashed up by the great Jack Dempsey.

Sometimes depression can be triggered by a lack of motivation for the thing that defines you, sometimes that lack of motivation is triggered by depression. Either way, Fury claims he hasn't been near a gym for months and has been drinking like a fish and hoovering up cocaine instead, in a forlorn bid to mask the pain.

Tyson Fury would 'sink further in soil' with boxing ban - Billy Joe Saunders

Fury's love-hate relationship with the media

In an interview with Rolling Stone magazine this month,, external Fury accused the British media of conducting a "witch hunt" against him and the British public of racism. It is important to separate the different links in Fury's sometimes rambling trains of thought.

Before and after his victory over Klitschko, sports writers openly discussed whether Fury should be saved from himself. Different journalists operate under different editorial guidelines, but the view of most was that they had been sent to Germany to report on a fight, not Fury's controversial outbursts.

As such, the repeated claims from Fury's camp that his victory was downplayed by the British media, and that they had an agenda against him from the outset, are delusional. Almost every boxing writer proclaimed Fury's performance as one of the finest ever by a British fighter, and they were right.

Tyson Fury has a good relationship with boxing reporter Steve Bunce as well as many Youtube boxing vloggers

But the problem with a siege mentality is that you forget what's happening beyond the castle walls, who your real friends are, and paranoia sets in.

When Fury threatened violence against a journalist and later took aim at bisexual, transsexual and Jewish people, it was internet vloggers - to whom he had granted intimate access - who provided the platform. The so-called mainstream media (newspapers and major broadcasters) had been frozen out, ironically because they had dared to report what he had told those same vloggers.

Fury's camp would do well to memorise a quote attributed to George Orwell: "Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printing. Everything else is public relations." How many times has Fury been saved by journalistic self-censorship?

In threatening that journalist, the Mail on Sunday's Oliver Holt, for reporting that he had compared homosexuality to paedophilia, Fury betrayed his sense of entitlement - not only because of his feats in the ring, but because of his religious convictions. If it's in the Bible, how dare anyone question his beliefs?

If you make questionable statements about gay people or Jews or women, the media will come down on you, whether you are a fine boxer, a deeply religious man, a nice bloke really, none of the above or all of them. Fury's Traveller heritage doesn't come into it, as least as far as most of the media is concerned.

Despicable social media abuse

"I know Tyson personally and he's a really nice guy," says Ricky Hatton, Fury's fellow Mancunian and another boxer who has struggled with depression. "But sometimes he puts his mouth into gear before his brain and when someone puts a camera in front of him he feels he has to say something outrageous."

Fury fans frequently claim that Anthony Joshua is given preferential treatment by the media, but this is because the IBF heavyweight champion - Fury was stripped of that belt shortly after winning it because he would not face the federation's mandatory challenger - largely conducts himself like a gentleman. As for Joshua's brushes with the law, they have been covered at length in the media and he has clearly learnt from them.

However, some of the racial abuse Fury receives on social media is despicable.

When you are called every name under the sun on a daily basis, it is likely to have an effect on your mental wellbeing. No wonder, as Fury also stated in his interview with Rolling Stone, that he feels like everyone is out to get him.

The British Boxing Board of Control may still strip Fury of his licence, despite his pre-emptive move to vacate his world titles

On Wednesday, the British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC) met to discuss what should be done with Fury, and has suspended his licence, pending a meeting with him. It could hardly do otherwise. It did the same to Hatton in 2010, also following allegations of cocaine use, and, as the BBBofC's general secretary Robert Smith has pointed out, "cocaine is against the law of the land".

There was also Fury's alleged use of performance-enhancing drugs and a subsequent ban to consider (Fury has an appeal hearing scheduled in November), as well as the allegation that he refused to take a drugs test (a misdemeanour that can lead to a four-year ban) and the argument that a man with severe mental health issues shouldn't be anywhere near a boxing ring.

Boxing needs to move on

It should also be remembered that the BBBofC has already fined Fury twice for misconduct and that it has boxing's image to think about - as mad as that sounds.

Even if Fury hadn't voluntarily given up his belts, the WBA and WBO would have stripped him of them.

Ricky Hatton (right) is a close friend of Tyson Fury and went through similar mental health problems in 2010 after he lost his boxing licence

It might seem callous, but the sanctioning bodies are businesses, the heavyweight belts are their biggest money-spinners and it is only fair that other boxers should be allowed to fight for them. It makes no difference whether a boxer has meningitis, a broken leg or mental health issues, the sport must move on. As WBO chief Jose Izquierdo put it: "We can't have a belt held hostage."

One can only hope that, during his absence from the ring, Fury gets the help he so desperately needs and returns fitter and more focused.

"Being someone who lives by the seat of his pants and for the moment, this could be the end of him," was Hatton's grim assessment. "He doesn't like boxing and finds the training hard. It's not looking good.

"But I was in a dark place, didn't care if I lived or died. I did very well in boxing but near enough everything wrong in life. The only way I got out of it was by asking for help. I fought through it and I hope Tyson can do the same."

Fingers crossed that Fury will be remembered for that fine performance against Klitschko in Dusseldorf - and for many fine performances in the future - rather than as a wreck, spewing smoke on the side of the road as bright lights flash by.

- Published13 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published12 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016