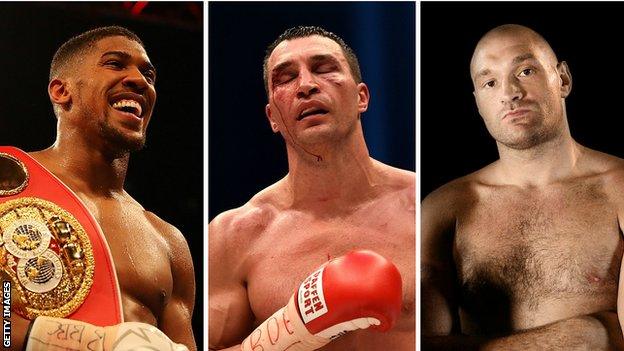

Anthony Joshua, Wladimir Klitschko and the 'fumble in a jumble sale'

- Published

Anthony Joshua, Wladimir Klitschko and Tyson Fury have become embroiled in an 'unseemly, confusing free-for-all'

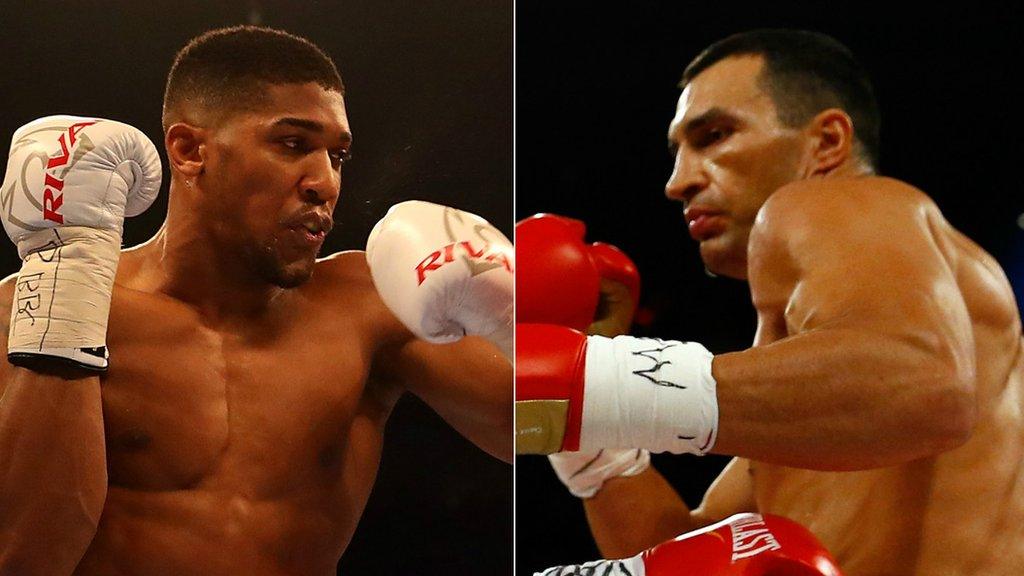

A match between Anthony Joshua and Wladimir Klitschko may seem as natural as ham and eggs. But boxing dishes, concocted on the hoof by a chaotic confederation of quarrelsome cooks, too often make no sense.

The day after Joshua's promoter Eddie Hearn announced the deal with Klitschko was virtually done, he announced the dish had been removed from the oven. And fans were left frothing at the chops and whining like dogs.

When Tyson Fury gave up the WBA and WBO heavyweight titles, citing mental health issues, Joshua-Klitschko seemed inevitable. But 'boxing' and 'inevitable' don't belong in the same dictionary, let alone the same sentence.

Fury won the belts from Klitschko last November, but when the troubled Mancunian pulled out of a scheduled rematch, the Ukrainian was at a loose end and seemingly ready for action. Meanwhile, Joshua had picked up the IBF title, which Fury also won from Klitschko but was stripped of for not defending against the mandatory challenger. What could possibly go wrong?

Hearn explained that both camps had submitted requests to the WBA to sanction the fight. He assured us that any potential conflicts between various broadcasters had been sorted. It was reported a match between the unbeaten Joshua - the coming man in the heavyweight division - and the veteran Klitschko - a man some believe to be past it - was worth in the region of £25m.

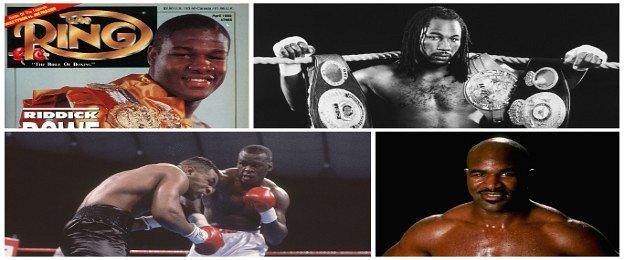

There have only been five undisputed world heavyweight champions since 1978 and none since 2000: Riddick Bowe, Lennox Lewis, Evander Holyfield, James 'Buster' Douglas and Mike Tyson

It then emerged Klitschko was refusing to sign unless the WBA belt was on the line and the Panama-based sanctioning body was stalling. More than a fortnight later, the WBA still hasn't made a decision as to whether to sanction the contest. World Boxing Association? More like What Blessed Anarchy is this?

Last Tuesday it was reported that Klitschko had suffered a minor calf injury and wouldn't have been able to fight Joshua on the suggested date of 10 December anyway. But a day later, Klitschko's manager Bernd Boente said his charge would have been ready but actually the fight needed more time to marinate.

Both camps suggested they should meet next spring instead, although presumably only if the WBA has seen sense by then.

Joshua will now defend his IBF title against American Eric Molina in Manchester on 10 December, because New Zealand's Joseph Parker chose to fight Mexico's Andy Ruiz for the vacant WBO belt instead. Molina was knocked out on his pro debut, again in one round by Chris Arreola in 2012 and again by WBC champion Deontay Wilder (who is currently injured and inactive) last year.

According to Boente, Klitschko is desperate to regain the WBA belt he lost to Fury in Dusseldorf. "Wladimir has always been a very loyal and committed WBA champion," said Boente, "and the WBA has always been a very important belt."

But Boente's explanation is dubious, to say the least. During his two reigns as a world heavyweight champion stretching back to 2000, Klitschko held the WBO title for 121 months; the IBF title for 115 months; and the WBA title for only 40 months. Perhaps more pertinent, the WBA is widely regarded as a shambles.

The WBA believes having one title holder in each weight division is not enough. So if a fighter owns a WBA belt in addition to one or more of the other 'big three' world title belts - WBC, IBF and WBO - he is elevated to 'super' WBA champion. Below that is the WBA's 'world/regular' title, meaning some boxers masquerading as world champions don't even top the WBA rankings.

An example of this is British super-bantamweight Scott Quigg, who 'reigned' as a WBA world champion between 2013 and 2016, despite the inconvenient fact that gifted Cuban Guillermo Rigondeaux - the man nobody wanted to fight - was the WBA's 'super' champion for much of that time.

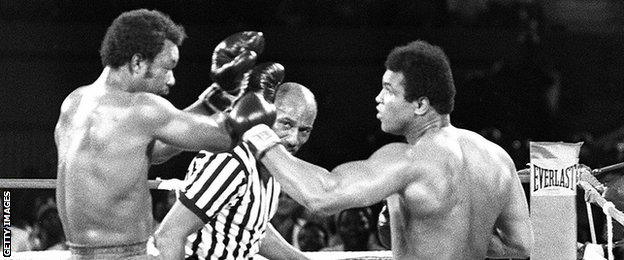

The fabled 'Rumble in the Jungle' between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in 1974, the current heavyweight scene is like a fumble in a jumble sale

Some boxers even claim to be world champions by virtue of owning a WBA 'interim' belt, which is effectively the EFL Trophy of WBA titles.

There are also WBA 'continental' champions (for those who live on a continent, presumably), 'inter-continental' champions (fought for by David Haye and Dereck Chisora in 2012, despite the fact they are both British), 'international' champions (nope, haven't got a clue either) and 'inter-planetary' champions (I made that last one up, although it may only be a matter of time).

WBA president Gilberto Mendoza has vowed to clean up this mess and return to a situation where it only has one champion in each division.

But nature abhors a vacuum. So while the WBA is silent, rumours swirl that Australia's Lucas Browne will fight 44-year-old American Shannon Briggs for a WBA heavyweight belt. For which WBA belt, nobody seems to know.

Meanwhile, Cuban Luis Ortiz, who recently signed with Hearn,, external is scheduled to defend his WBA 'interim' title on the Joshua-Molina undercard. By dint of being its 'interim' champion, Ortiz is ranked number one by the WBA. Browne is ranked number five and Briggs number eight. If it's of any consolation, I'm almost losing the will to live having to explain all this.

Some have accused Klitschko of attempting to duck Joshua and bringing shame to himself and the once great heavyweight division. But the real problem here isn't Klitschko - or any other boxer accused of taking a path of less resistance - it is the lawless world of boxing, in which sheriff's badges are handed out like Smarties and anyone with a bit of bling around his waist can claim to be king.

Fury's victory over Klitschko looked like it would bring continuity and clarity to the heavyweight division. But Fury's fall from grace - if you could ever call him gracious in the first place - has created an unseemly, confusing free-for-all.

Forget the Rumble in the Jungle, this - to borrow a quote from a TV executive from another era - is more like a fumble in a jumble sale.

- Published1 November 2016

- Published26 October 2016

- Published24 October 2016

- Published20 October 2016

- Published13 October 2016