Muhammad Ali: Sir Michael Parkinson 'proud' of legendary interviews

- Published

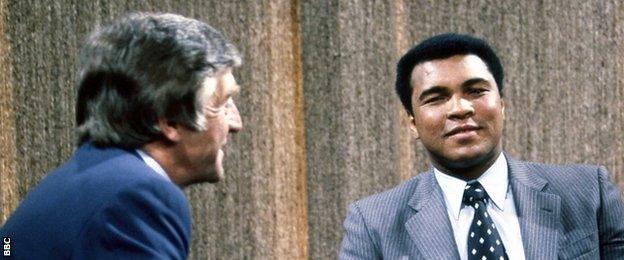

Muhammad Ali and Michael Parkinson in 1974 - the third of four interviews

Sir Michael Parkinson giggles uncontrollably, so that tears begin to well in his eyes and he struggles to finish his sentences. A broadcasting giant reduced to a schoolboy simply by a memory of Muhammad Ali. It is wonderful to witness.

Parkinson is recalling the third of four interviews with the greatest sportsman the world has ever seen. This was the one when Parkinson decided to challenge Ali on his controversial beliefs, the boxer got angry and things got rather serious.

"Ali's eyes were the giveaway. Usually when he said something terrible his eyes would be laughing. But not this time. This time his eyes were angry.

"He'd launched into a diatribe about how whites hated blacks, including the observation that I was too small mentally and physically to 'trap' him on my TV show. So the atmosphere at the Mayfair Theatre was extraordinarily tense.

"When I threw it to the audience, Brian Clough put his hand up and said: 'Nice to see you again, Muhammad.' And Ali leaned into me and mumbled: 'Who is this guy?' But Brian carried on regardless: 'You lost your cool with Michael, Ali, and he would have won. But Michael, you lost your temper as well…'"

Archive: Ali's famous interviews

It is at this point that Parkinson begins to dissolve, at the absurdity of being involved in a life-or-death talk-show tussle and Clough - the former Nottingham Forest and Derby County manager - offering to referee.

Afterwards, Parkinson retreated to his dressing room to conduct a mental post-mortem - "What could I have done differently? Why was he offended?" - when his dad knocked on the door and demanded to know what had gone wrong.

"My dad, who was a miner at Grimethorpe Colliery, said to me: 'What was up with you?' I said: 'What do you mean, what was up with me? What else could I do?' And he said: 'Why didn't you thump him?' I couldn't stop laughing."

When Ali died in June, Parkinson's phone did not stop ringing for days. But, like almost everyone else, he felt he struggled to pay sufficient tribute.

"You could only give the impression of getting a grip on him as he flashed by," says 81-year-old Parkinson, who has written a book about his sparring sessions with Ali.

"I never had the chance to do the interview I wanted to do, because he'd just drop a bomb and I'd be left with a tattered script I couldn't make sense of. He'd do you up like a kipper, completely overwhelm you with his huge personality.

"He never stopped talking, although a lot of what he said was nonsense. He said he hated white people, but he didn't hate me. He'd say: 'You're different, you're English.' He thought relationships with women should be pure, but he had many affairs. He was perverse. But you could never deny his basic beliefs.

"It was possible to think of Ali as a loudmouth - but he was a lot more than that, to black Americans in particular. For all his madness, he was a serious man."

Muhammad Ali: "I wear one suit a day, I can only eat one meal a day, I can drive one car a day"

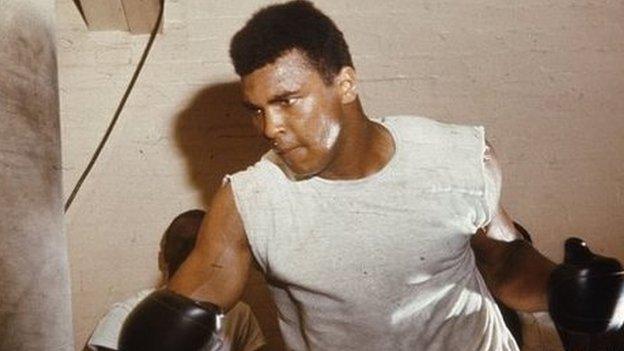

Parkinson first interviewed Ali in 1971, six months after his defeat by Joe Frazier in 'The Fight of the Century'. The media built it up as if it was a boxing match - and while the first Frazier fight proved that Ali's three-and-a-half-year ban from the ring had diminished him as boxer, his charisma had not been dimmed.

"There was huge public interest before that first interview, and he didn't let us down. When you first met him, you couldn't believe it. He was such a big, graceful man, so good-looking and very imperious, as if to say: 'You won't be meeting many people like me in your life.' He was right, nobody came close.

"I'd interviewed people I'd admired since childhood, like Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly and all the glorious Hollywood women I'd fallen in love with. But Ali was real and tangible and there was a sense of wonder about meeting him."

Parkinson with George Best, Bing Crosby, Nelson Mandela and Henry Kissinger

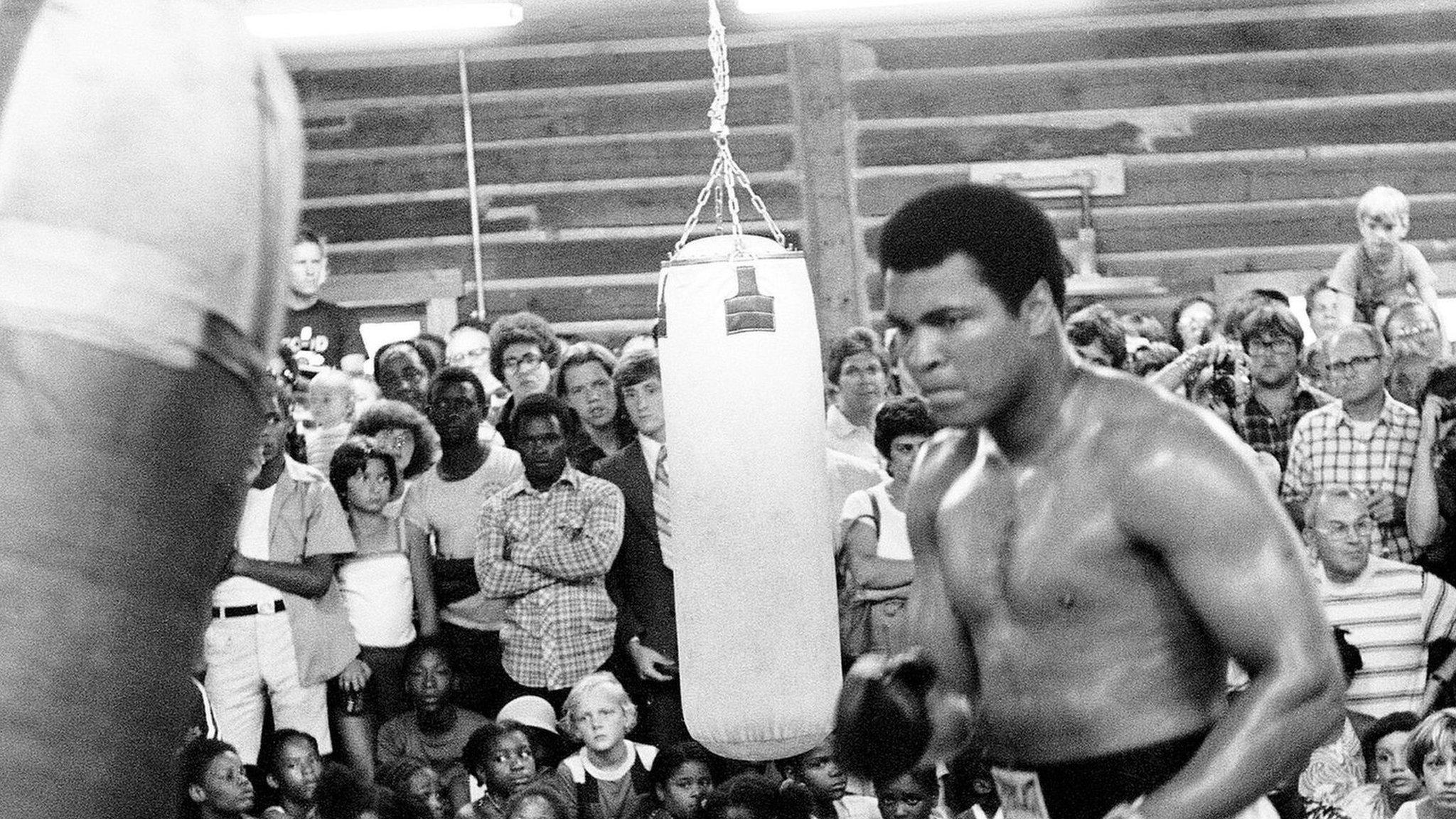

The second time Parkinson interviewed Ali was as part of a joint venture with an American production company, only a few days before his second fight with Frazier. Frazier was also in attendance, meaning Ali was at his ugliest.

"Ali was horrible to Joe Frazier. Frazier was charming, a really nice man, he just didn't have what Ali had. He wasn't articulate, so Ali was an awful bully towards him. Frazier was also brought up in abject poverty and represented all that Ali was supposedly fighting for. Yet Ali called him an 'Uncle Tom'."

This being American TV, the two rivals almost came to blows. Or at least Frazier thought they almost came to blows, because Ali was only kidding.

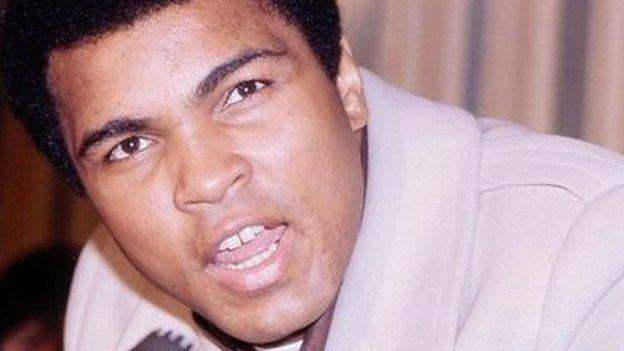

Parkinson's fourth and final interview with Ali, in 1981, was a more reflective affair. Two months earlier, the shell of Ali had been drummed into submission by his former sparring partner Larry Holmes, who wept after his hollow victory.

"That interview was autumnal. He was not well, his voice was slurred and I felt so sad, because I knew I'd never see him again. We all knew what was going to happen, it was like watching a great tower being demolished in slow-motion."

When Ali was voted BBC Sports Personality of the Century in 1999,, external Parkinson was asked to present the award. He declined, feeling "unable to encounter at close quarters that once glorious man now wrecked by a terrible illness".

By the time of Parkinson's fourth interview in 1981, Ali's speech had slowed down appreciably

Almost 20 years had passed since their previous meeting but Parkinson preferred the memories. And he could still relate to the actor Liam Neeson, who when introduced to Ali as a young man could only muster: "I think I love you."

"I'm so proud of those interviews. Parts of them are rough and ready but we got some things right and you come away with the impression of a remarkable man.

"I didn't like him to start with, but then I got to understand him better. I wasn't angry [after the third interview in 1974]. I understood that he just meant things for the moment. I liked the fact he had balls and didn't care who he offended.

"Journalists are lucky in terms of the access we have to famous people. But only a few make you think: 'That was a privilege - what an extraordinary person.'"

- Attribution

- Published4 June 2016

- Published4 June 2016

- Published4 June 2016