Jerome Wilson: Coma boxer 'feared something bad might happen'

- Published

Welterweight Wilson, 29 at the time, lies on the canvas after being knocked out by Serge Ambomo on Friday, 12 September 2014.

Jerome Wilson saw it coming, except he didn't know it. Call it a fighter's sixth sense, call it an unconscious premonition. Cynics might call it common sense.

The day before the fight that wrecked his life, Wilson suddenly felt compelled to send a message to his partner's son.

"I don't fear any man and I didn't fear Serge Ambomo," says Wilson. "I'd never done anything like that. But something must have been telling me something bad was going to happen."

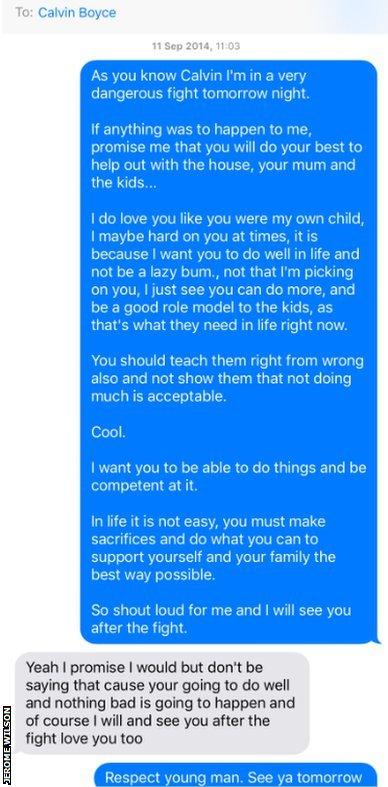

Wilson's text message began: "As you know, Calvin, I'm in a very dangerous fight tomorrow night. If anything was to happen to me, promise me that you will do your best to help out with the house, your mum and the kids."

Wilson told Calvin he loved him, to try harder, to be a good role model and that he would see him after the fight. Calvin replied that everything would be all right.

Jerome texted his girlfriend's son the day before the fight with some advice as he feared something might happen to him

When Calvin saw Wilson after the fight, everything was far from being all right. Having suffered a bleed on the brain, Wilson was deep in a coma, being kept alive by tubes.

Nobody knew which punch had caused it - the right hand that poleaxed Wilson in the second round? The right hand that finished it? - and nobody ever will. When the man you love is virtually dead, it's kind of irrelevant.

Jerome Wilson was in a medically-induced coma for 10 days

"About a week before the fight, I was having wild dreams and a couple scared me," says Wilson's girlfriend, Michelle Boyce. "In one of them, Jerome had been seriously hurt and ended up in a coma. It felt so real. I remember walking into the emergency room, kissing his head and saying: 'Don't you dare leave me.' When I woke up, I rang him and said: 'I don't want you to take this fight.'"

After the first fight between Wilson and Ambomo (a barnstorming six-rounder in Wilson's home town of Sheffield four months earlier, which Ambomo won on points), Boyce had to remove Wilson's clothes and help him into bed.

"Before that, he had come out of fights fine, maybe with a cut lip," says Boyce. "But that time I remember thinking: 'This is quite dangerous. I don't like this.'"

In the relatives' room at the hospital, Wilson and Boyce's three-year-old daughter, still wired after seeing Daddy fight for the first time, ran amok. Along the corridor, doctors told Wilson's family that he might not live another day.

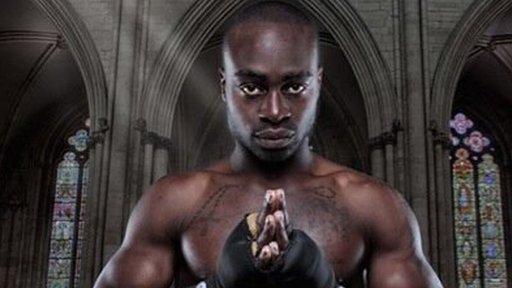

Jerome Wilson in his prime, before his career ending fight in September 2014

A quarter of Wilson's skull was removed, to ease the pressure on his brain, and a fighter's furious spirit kicked in. Boyce, heavily pregnant, stood vigil. And as she waited for a miracle, Wilson drifted in a strange, parallel universe.

"I was living in a reality that didn't exist," says Wilson, who was 29 at the time. "When I awoke from my coma after 10 days, I thought my dad was dead. So when I saw him sitting on the end of my bed, I was very happy to see him but couldn't grasp why he was there. I didn't know what was real and what wasn't.

"I thought I had been communicating with people. My mum kept saying, 'say I love you', and I thought I was. When I woke, she told me I hadn't said anything.

"When Ryan Rhodes [a former British champion and Wilson sparring partner] came to visit, I told everyone to leave the room. When we were alone, I took his hand and said: 'I'm so sorry for everything that's happened.' I thought I'd provoked a fight with Ryan and that it was him who had put me in hospital."

Wilson slowly pieced together what was real and what wasn't, while wrestling with the indisputable truth that life would never be the same again.

"Those early days were the darkest," says Wilson, fighting back tears. "I wanted to be the same person I was before, but had to somehow accept that I wasn't.

"Processing information took longer, my mind was not working how I wanted it to work. I was in chronic pain because of nerve damage. My mood would go up and down, depending on how my body was feeling. Sometimes I was depressed.

"People would see me and say: 'You're looking well!' I wouldn't want to complain - people don't want to hear that - so I'd put on a happy face. It's frustrating when people think everything is fine and you know things aren't.

"But if you think you're fighting a losing battle, all the will goes out of you. It's a fight I have to take, and I'm winning. If I had no happy days, life wouldn't be worth living. But the smile on my kids' faces gives me the energy to continue."

Eleven months after emerging from his coma, Wilson had a titanium plate inserted in his skull. It made him feel safer - "before, it felt like I could touch my brain and that it might pop out" - but he was still wary of sneezing.

Titanium plate in place, staff at the Sheffield Community Brain Injury and Rehabilitation Team began rebuilding Wilson's shattered mind and body - always with the knowledge that he would always be missing pieces.

Jerome with his daughter Serenity and son Cairo. He subsequently had a titanium plate inserted in his skull

Meanwhile, Wilson grew bitter over his perceived treatment by the British Boxing Board of Control, which he accuses of treating him "like rubbish".

"When I came close to taking my own life, I knew I had to seek help but there was no help for nearly a year," says Wilson. "When you hold it all inside, your mind eventually erupts and the lava burns you, inside and out.

"Every fighter should get respect. I have not received that from the Board, not even the simple question: 'How can we help?' The duty of care is non-existent. I feel like I've been used and tossed out to rot. It's hard to take."

Robert Smith, the British Boxing Board of Control's general secretary, sees things differently. These are testing times for Smith, who is currently investigating the circumstances of Nick Blackwell's latest injury - the Wiltshire boxer ended up in a coma after his fight with Chris Eubank Jr in March and is in a coma again after an ill-advised sparring session a couple of weeks ago.

"Jerome hasn't been ignored," says Smith, who also saw German boxer Eduard Gutknecht punched into a coma by George Groves at Wembley last month.

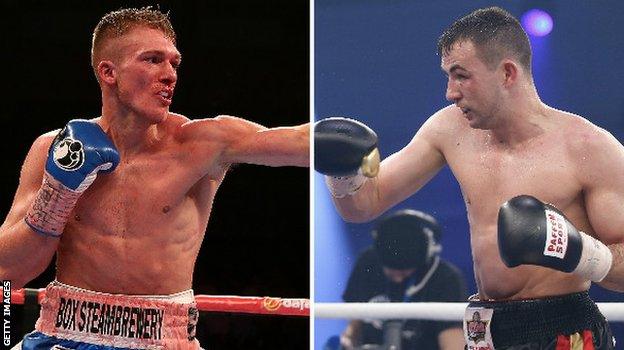

Nick Blackwell and Eduard Gutknecht have both ended up in comas after fights this year

"We've had lots of correspondence with Jerome, he's been visited on numerous occasions by the Central Area council and the Board. The insurance claim is ongoing - these things take time - and we've given him money. If he asks for more assistance, I'm sure the Board will look into it. All he needs to do is ask.

"We are one of the only countries in the world that has an insurance policy. We advise boxers to take out further cover, but not one boxer has taken our advice. We can only do so much. Boxers have to take some responsibility themselves."

For Boyce, who gave birth to a son not long after Wilson left hospital, any advice is too late. In her opinion, nobody should get into a ring in the first place.

"Boxing was in Jerome's blood but I don't like it," says Boyce. "When it goes wrong it can be shattering for everyone involved. And it only takes one punch.

"Boxers don't get the right information. All these lads see the razzmatazz, names in lights, the cars, the women, the houses and it doesn't work out like that for most people. They should be made aware that they're risking their life and if things go wrong, they might not be able to look after their family.

'Nobody to blame' for Blackwell injury

"Jerome got promised a lot of things that never materialised. He was good when he was getting his head caved in, now he's been thrown on the scrapheap."

Plans in boxing are not worth the paper they're written on. Fighters are fired into the game like ball bearings in a pinball machine - which way they travel and how long they last before being swallowed up has a lot to do with luck. But Wilson has adopted the attitude that such an analogy could apply to all of life.

"I've watched the fight back," says Wilson, whose free treatment by the NHS will shortly come to an end. "It was like watching a ghost, it wasn't me in there.

"But I try not to think about what might have been, if I'd done this or done that, because it can send you a bit crazy. And if I hadn't boxed, I might be dead. So I don't think people can use what happened to me as a reason to ban the sport.

"When I was in rehab, lots of people were in a very bad way but I was on the only person in there because of boxing. People had been in car crashes, fallen down the stairs, slipped over in the bath. Boxing is dangerous. But so is life."

- Published23 September 2014

- Published30 November 2016

- Published12 April 2016