Mike Costello: Golovkin-Jacobs evokes Leonard-Hagler memories

- Published

- comments

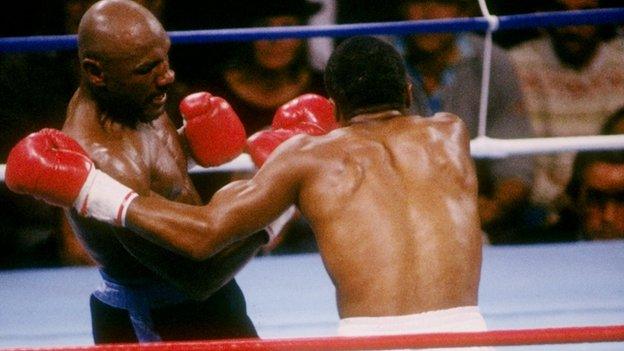

Some 30 years after Hagler-Leonard, scoring matches still proves controversial

The recent world middleweight title fight between Gennady Golovkin and Daniel Jacobs was the latest example of a major showdown ending in controversy over the scoring. But will we still be arguing the toss in three decades' time?

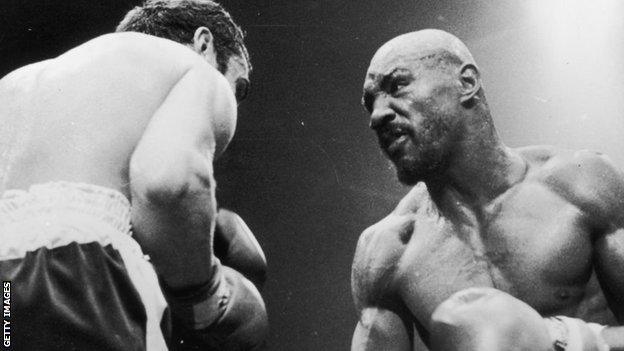

Next week marks the 30th anniversary of 'The Super Fight', when Sugar Ray Leonard outpointed Marvin Hagler at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas to win the WBC middleweight crown that still belongs to Golovkin courtesy of his points win.

The headline in the American magazine Sports Illustrated read "SHOCKER" and in all my time involved in boxing in various guises, no fight of such magnitude has created such debate for so long.

In a classic confrontation between aggressor (Hagler) and counter-puncher (Leonard), front-foot prowler versus back-foot stealer, Leonard was awarded a split decision win in a monumental upset that sent Hagler into retirement in his early 30s.

Back then, big fights in Vegas were staged on Monday nights, with high rollers invited to spend (and spend!) all weekend at the gaming tables before heading to the converted car park on fight night.

Here in the UK, satellite TV had yet to arrive in homes and I watched the contest in the early hours of Tuesday morning on a closed-circuit screening at the Royal Festival Hall on London's South Bank. From my plush and plump-cushioned seat, I made Leonard the winner by eight rounds to four.

But were those of us who sided with Leonard - including two of the ringside judges - guilty of succumbing to what the great sportswriter Hugh McIlvanney labelled the "Illusion of victory"?

Leonard had not fought in nearly three years before meeting Hagler and spent 19 months out of the ring afterwards

Hagler was making the 13th defence of the world middleweight crown he had wrested from Britain's Alan Minter at Wembley Arena in 1980. Leonard had been absent from the ring for three years and had fought only once in more than five years for various reasons, among them surgery on detached retinas.

Rarely had he boxed above welterweight and yet he was prepared to move up to the middleweight limit, a stone heavier, without a warm-up fight to take on one of the greatest 160-pounders of all time. An act of hubris or lunacy?

McIlvanney wrote in The Observer newspaper about the Budd Schulberg factor, put forward by the Oscar-winning screenplay genius, whereby those of us in thrall to Leonard were "so amazed to find Sugar Ray capable of much more than they imagined that they persuaded themselves he was doing far more than he actually was".

There were many keys to Leonard's success but two factors stand out.

His trainer Angelo Dundee, who was in Muhammad Ali's corner almost from start to finish, wrote in his autobiography 'I only talk winning' that he had noticed how Hagler needed two steps to get into position for his most telling punches. Leonard's quickness of mind and foot was programmed to exploit.

Also, the WBA had stripped Hagler of their version of the world middleweight title when he refused to defend against Britain's Herol Graham. Only the WBC belt was at stake - and the WBC had reduced their championship fights from 15 rounds to 12 in the wake of the tragic death of the South Korean Duk-Koo Kim in a fight against Ray Mancini in 1982.

Hagler's meeting with Leonard was his 67th and final fight

Over 15 rounds, Hagler might well have proved too strong. Over 12, he seemed to be playing catch-up.

For some, including McIlvanney, the 'Marvelous' one was "cruelly misjudged" anyway. For me, the theory of illusion might have held sway on the night but I have watched the re-run many times and cannot fathom how Hagler could be adjudged the winner.

I was, though, a Leonard fan and so have to accept that my reckoning might be influenced by irrational leanings. Whatever our vantage point, we are bound to favour one style over another, one personality against another, and an unconscious bias is present in most of our verdicts.

The three judges sat on raised perches at ringside will claim that experience instils in them an umbilical attachment to neutrality but even they cannot be rendered immune from such tendencies.

As long as there is boxing, there will be controversy over judging. But how many of the arguments will last for 30 years?

The fighting 'disease'

James DeGale has had 25 bouts but has vowed to leave the fight game on his terms

Gene Tunney, Rocky Marciano, Carlos Monzon, Lennox Lewis and Vitali Klitschko all quit at the top but each bowed out on a win at world championship level. Joe Calzaghe also departed on a win - and on his own terms.

Hagler somehow stepped away on the back of a defeat, with the temptation to return diluted by his failure to lure Leonard into a rematch. Even so, there were lucrative options he chose not to take up.

James DeGale was honoured this week at a special lunch organised by the Boxing Writers' Club at Little Italy in Soho and in an interview recorded between courses he vowed to emulate those in the minority who had navigated their own exit route.

"I will retire before boxing retires me," he promised.

When I pointed out that they all say that, his response was prefaced with a knowing chuckle: "Elite fighters need protecting from themselves. It's a bug, a disease and once you're hooked, you're hooked."

The elusive win to top the ascent

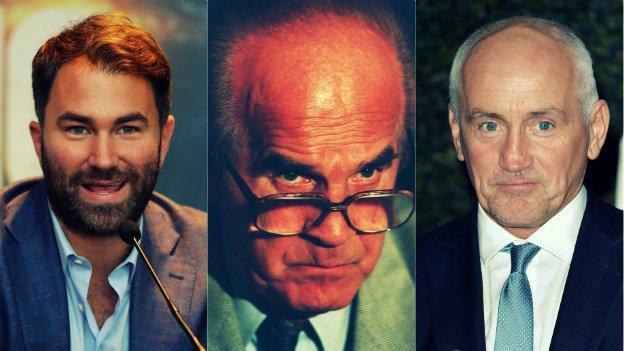

Duff (centre) spoke of the art of match-making while Eddie Hearn (left) and Barry McGuigan (right) have seen their fighters beaten at the elite level recently

The late Mickey Duff, respected and despised as much as any manager or promoter, once told me in an interview that "a match well made is a fight half won".

His maxim came to mind in reflecting on a busy spell of boxing on BBC 5 live so far in 2017. We have commentated on world title fights featuring British boxers in New York and Las Vegas, Hull and Manchester - and none of the Britons won.

DeGale drew against Badou Jack, Carl Frampton lost out in his rematch against Leo Santa Cruz, while Gavin McDonnell and Anthony Crolla finished a distant second in the company of Latin brilliance. The results serve as confirmation that, whatever influence and judgment a manager or promoter exerts in securing opportunities for a boxer, standing firm at the top is often harder than the climb to the summit.

Crolla upended the odds to beat first Darleys Perez and then Ismael Barroso in world title fights and home advantage was vital in both successes, delivered by his promoter Eddie Hearn.

Then Crolla bumped into Jorge Linares and discovered a different class. Linares is not only well-travelled but travels well and yet he would not warrant a place in the world's top 10 pound-for-pound rankings, except maybe in a vote among his native Venezuelans.

In that context, how special were Leonard and Hagler?