'Anthony Joshua's win over Wladimir Klitschko makes him part of mainstream'

- Published

- comments

Anthony Joshua has won all 19 of his professional fights by stopping his opponent

So that was the night when a talented young sportsman supersized to become part of mainstream British culture.

Nothing will ever again be the same for Anthony Joshua, a prodigiously gifted boxer who in 11 rounds of twisting drama escaped not only the fists of Wladimir Klitschko and the dislocated senses that came from them but the tight boundaries of his chosen sport.

These moments come along infrequently but unforgettably, sometimes through great triumph, sometimes through desperate failure: a performer long appreciated in their own world who through one act or display jumps the barriers into an altogether greater sphere of fame.

Barry McGuigan overcoming Eusebio Pedroza at Loftus Road in 1985, Paul Gascoigne being yellow-carded in Turin in 1990. Bradley Wiggins and some yellow of his own on the Champs-Elysees before a throne at Hampton Court a few weeks later. Dennis Taylor and a black-ball finger waggle; Mo Farah and a Stratford Saturday night Mobot, Jonny Wilkinson, external and a late drop-goal on the other side of the world.

It doesn't matter if nothing else they do ever quite matches that initial impact. Into the national consciousness they have been stamped, from playgrounds to offices, dinner parties to dinner ladies, front pages to social media memes.

Joshua beats Klitschko - best moments memes & reaction

Joshua's coming of age was not witnessed by 18 million people on terrestrial television like Taylor's, nor was it part of a wider festival of surreal national success like Wiggins and Farah. Its impression instead comes both from what was expected and what actually transpired, from the way it was achieved, from the distinctive emotions boxing can still illustrate and stir.

This was a heavyweight title fight that appeared predictable - the short game for Joshua, the long one for Klitschko - and behaved any way but: the 41-year-old veteran initially resurgent and fluid, the young puncher putting his man down and then being stunned himself with celebrations still rolling round the arena. A cruel, lost period when Joshua somehow held on in the darkness, the slow assertion of tactical superiority by the old stager and then, from nowhere, the final shattering denouement, an uppercut to be felt around the nation, an explosion of blows and stumbling feet and raised arms.

It was boxing with the plot twists of Test cricket, turning with the speed of the critical holes of a Ryder Cup Sunday, a callow kid becoming a true champion in 11 rounds that felt simultaneously far longer and a breathless fast-forward that pushed everything else away.

There is no hiding place for pain and pleasure in boxing, no mask to disguise what a boxer is going through when his opponent's arsenal detonates. When the skin around Klitschko's left eye was opened up by Joshua's right hand early in the fifth, the shock was as visible as the Ukrainian's blood; when Joshua was nailed with a right cross early in the sixth, his legs gave in even as he tried to smile it away, his arms groping for the ropes and missing, his knees trying to straighten but failing.

It spells it out for those watching and it sucks them in. "Boxing is about character - there is nowhere to hide," Joshua would say afterwards, and in the manner that he came through the rest of that sixth round and clung on for the next two, he gave testimony to where the hype ended and heart began.

That fifth round in isolation was enough to make it the best heavyweight fight since the first Tyson-Holyfield ding-dong. The 11th deserves to stand alone too, a brutal eruption of speed and violence from Joshua, a heroic refusal from Klitschko to let go, rising once to be put down again, rising once more to be sent crashing for the final time.

Anywhere it had been staged it would have reminded those who long ago fell out of love with heavyweight boxing why they were drawn to it in the first place. With 90,000 to witness it at Wembley came a setting to intensify the intrinsic thrills.

Boxing in Britain has always drawn crowds to garland the big showdowns, from the 35,000 at Wembley that saw Henry Cooper's first fight with Muhammad Ali and the 46,000 that saw the two meet again at Highbury three years later, to the 40,000 for Frank Bruno's world title fights with Tim Witherspoon and Oliver McCall, the 47,000 at Old Trafford for Benn-Eubank in 1993 and the 80,000 for Froch-Groves II at Wembley three years ago.

Should those numbers desensitise you to the scale of the support, it is worth reflecting that Floyd Mayweather's fight of the century against Manny Pacquiao in May 2015 drew 16,507 paying customers to the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, Mike Tyson's meeting with Lennox Lewis in 2002 took 15,327 to the Pyramid in Memphis.

It doesn't matter that many of those in the further reaches of Wembley Stadium on Saturday night will recall the critical moments from distant screens rather than first-hand memory. If you were there, you went so you could boast of having done so. If you forked out on pay-per-view you made satellite executives rich and helped break records; if you listened on radio you were part of a collective that set even more.

Wladimir Klitschko's left eye was badly cut as he lost for the fifth time in 69 fights as a professional

If it passed you by on the night, it came to you in conversations and status updates across an otherwise slow Sunday. Replays on radio, reflections on news channels, memories received and given.

No live event this year has drawn a bigger audience to a single page on the BBC Sport website. Just as at London 2012, when Joshua won the last home gold medal of an extraordinary 17 days, Britons embraced a live sporting occasion like very few other nations.

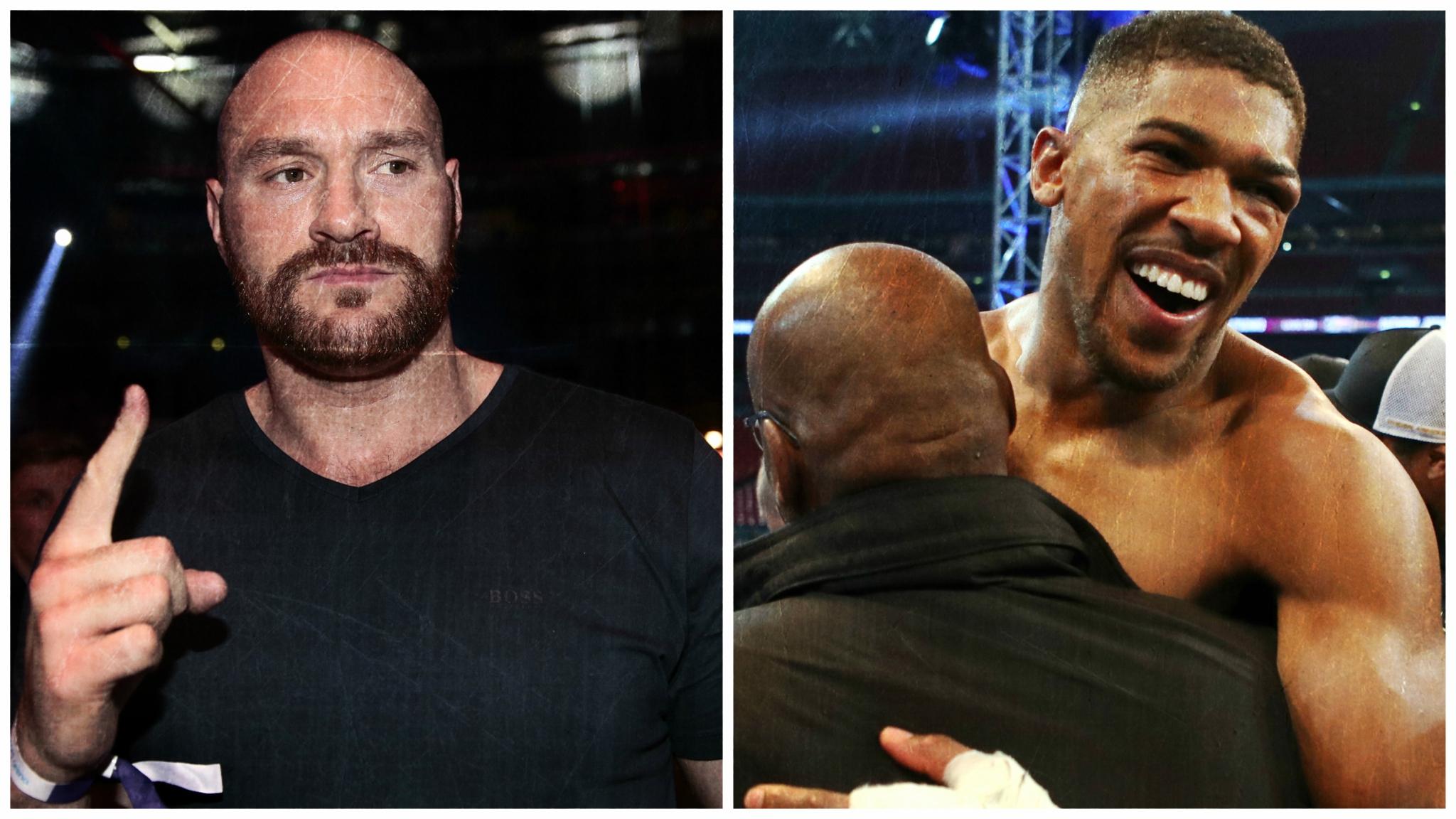

Boxing is a niche sport in many countries and unloved or forgotten in others. With 11 current world champions, Britain is entering an unexpected golden age that may yet produce more nights like Saturday, not least should Tyson Fury shed the weight and demons to line up another upset in his sights.

For now, this is all about Joshua, the everyday kid with just enough bad in his back story,, external the last sporting hero of 2012 and the first of 2017.

He may never again be involved in a fight as epic as Saturday night's. He may never have to prove more. Boxing may one day even sour for him. But he is unforgettable now, whatever Fury or future may bring.

'Not perfect' Joshua plans next steps

- Published29 April 2017

- Published30 April 2017

- Published30 April 2017

- Published30 April 2017

- Published30 April 2017

- Published22 December 2018