Jane Couch: The inspiring story of Britain's first female world champion boxer

- Published

- comments

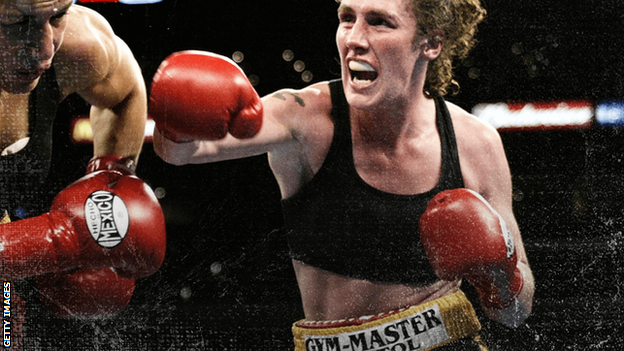

Jane Couch blazed a trail for female boxers in Britain

A version of this article was first published in June 2020.

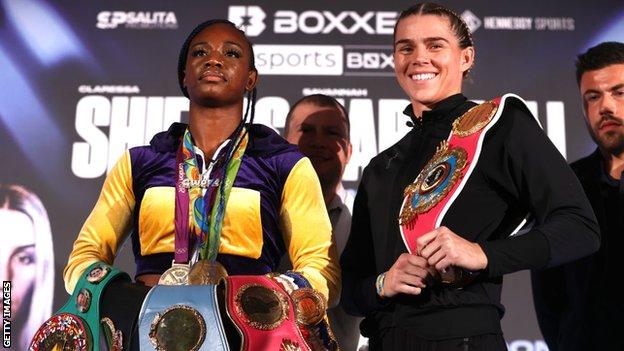

On Saturday night, Savannah Marshall and Claressa Shields will make history as the first female fighters to headline at the O2 Arena in London. It will be an all-female card, the first in the UK.

It is a landmark moment, 24 years on from another - the legal battle that allowed women the right to box professionally in this country.

Jane Couch was the fearless driving force behind that.

Now 54 and retired for nearly 14 years, she is a massive fan of Marshall - a big-punching 31-year-old from Hartlepool who has had to overcome many of the same challenges Couch did, despite the decades separating their careers.

Marshall considered walking away from pro boxing several times, fearing her talents would never be recognised or properly compensated.

She stuck it out and could now become a household name if she beats the seemingly unstoppable 27-year-old American Shields.

Boxing is a fight, but Couch had to fight just to box. Future generations might skip the chapter about what she achieved, but they shouldn't.

Thanks to her, British women can now walk into a boxing gym and feel accepted - they no longer need train in secret.

Couch paved the way for fighters like Marshall.

This is her story.

Born in 1968, Couch grew up in Fleetwood as one of four siblings. As a teenager she would often brawl in the streets. It led to her expulsion from school.

She has described the years that immediately followed as "a life of booze, drugs and street fighting". But there was something else going on too.

"I used to tell my mum all the time," she says. "'I'm going to do something big. I just don't know what it is.'"

Couch moved to London at the age of 16, following her punk rock brother. After pulling pints in pubs during the week, she would return to Fleetwood to meet up with friends and the street brawls continued.

She doesn't know how many times she was arrested, for jumping through a jewellery shop window, for scrapping on the street or driving without a license. After spending three months in prison, something had to give.

It all started with a Channel 4 documentary about two female boxers, the American Christy Martin and Ireland's Deirdre Gogarty. It sparked a change. It's how Couch's journey in the sport began.

"Women are allowed to box! I couldn't believe it," she says. "The next day I went to the gym, but was told that women couldn't box in this country.

"I thought, I've got to pursue this, I have to. I have to be allowed to box like the girls in the documentary."

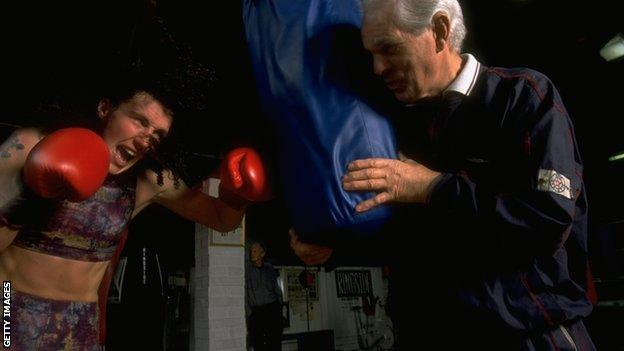

Couch, pictured training at a gym in Birmingham in 1997

That was in 1994. Couch was 26, and boxing was illegal for women in the UK. The sport was unlicensed in the country but, still, fights were taking place.

First though, if Couch wanted to fulfil her ambition of being a female boxer, she needed a gym and a trainer. In Fleetwood she found both.

Frank Smallbone took her on in a local gym where she was for a while able to train in secret. When word got out, things got ugly.

"You'd read articles in the papers saying, 'she must be a lesbian, she must be this, she must be that, she's a freak'," Couch recalls.

"You become labelled with this horrible label, just because you want to take part in a 'man's sport'."

Couch's first bout was in Wigan against a policewoman called Kalpna Shah. "I knocked a copper out and got paid for it," Couch says. "I think I got £58."

It is a far cry from the $1m (£870,000) each Katie Taylor and Amanda Serrano received in April for their undisputed lightweight fight at Madison Square Garden. Shields' two-fight deal with Sky Sports, which included her win over Ema Kozin in February, is also worth a reported $1m (£870,000).

Before Couch knew it, 'the Fleetwood Assassin' had four fights and four wins to her name. She had very little money, but a growing reputation set up a world title fight against Frenchwoman Sandra Geiger in Copenhagen, in 1996.

Geiger was a big name. She had 29 wins, 29 knockouts. She was the favourite. Couch was not fazed.

"I was convinced I would beat her," she recalls. "I was like something possessed. I knew by beating her and bringing the world title home it would change."

Couch did win the belt, and it altered perceptions of her in the UK. But an incident before the Geiger fight provided a stark reminder of just how far away real change was.

After starving herself for the weigh in, all Couch wanted to do was eat. She went to reception armed with vouchers for her long-awaited meal.

"Sorry, the vouchers are only for the fighters," came the response.

Couch replied: "I am boxing for the world title."

Silence. Then: "These meal vouchers are only for the male fighters."

From 2018: The boxing world champion who paved the way for others

Most fighters will tell you they can deal with the physical pain of boxing, the jabs, the hooks and the uppercuts. That the most sickening blows take place outside the ring. That the real frustrations are with landing fights, or dealing with agents and promoters. Or in Couch's case, winning her licence to fight in the first place.

She was determined to make change happen. It took her three years to get her day in court. She needed the help of Diana Rose and the late Sarah Lesley, who were both working pro bono, and the backing of the equality opportunity commission.

"It was three women against the establishment, and it was the last male bastion that we knocked down," Couch says.

They were trying to overturn the British Boxing Board of Control's decision to refuse her licence. Part of the reasoning behind that decision was that, being a woman, pre-menstrual syndrome made her 'too unstable to box'.

Couch had been fighting for around four years. Sometimes overseas, other times in unlicensed bouts in the UK. She was a world welterweight champion, but still portrayed as something of a pariah. The oldest boxing paper in the land, Boxing News, steadfastly refused to cover women's boxing at that time, because it wasn't licensed.

In March 1998, Couch was successful in her claim for sexual discrimination against the British Boxing Board of Control. She had won the right to box professionally in the UK. It was a landmark ruling.

"I thought, everything is going to change now, I'll be able to get on shows at home and get better paid," Couch says. "It was a great day. I don't think I'll ever forget it, we three women hugging each other and thinking we're going to change everything.

"But then as I was leaving the courtroom Diana said to me: 'You do realise this is just the beginning'. I never knew what she meant, until now."

Acceptance did not come overnight. The pre-eminent British promoters of the time still didn't want anything to do with Couch and were vocal about it.

One of the most prominent, Frank Warren, didn't promote a female boxer until the latter part of the 2000s. For months after winning her right to fight, Couch still found herself a polarising figure. They asked on talk shows: Was it really OK to allow a woman into the ring?

"I don't know why I carried on, because winning that case had no benefit to me whatsoever," Couch says. "I still had to box abroad, I was still berated by the press. I was still frozen out by promoters in this country. I walked into a room and people laughed. So no, the case wasn't worth it."

The "stigma" as Couch puts it, might be fading but it still exists.

Today, the British Boxing Board of Control lacks female insight. It is the regulator of the sport, overseeing hundreds of shows a year, appointing referees, judges and handing out licences to fighters.

There are just seven women appointed to the various area councils across the UK - none on the main board, aside from one serving as a 'steward of appeal'. There are two female 'honorary stewards'.

"The stigma has continued," Couch says. "You only hear about the top fighters who are doing alright. But there are women right now trying to train, raise children and work.

"On the board they're mostly all men. I think there's one woman referee right now. No women judges - boxing in the UK has still got a hell of a lot to go for women."

It certainly didn't make financial sense to carry on during her era. Couch was crowned world champion five times, but her best pay day came from a 2003 bout she took on 12 days' notice, against the fearsome Lucia Rijker in Los Angeles.

Couch, beaten by the Dutchwoman, was paid £7,000 but cleared just £1,500 after taxes and managers' fees. She admits she often fought for nothing, just to stay busy.

In common with most fighters, Couch carried on for too long. Her final punch was thrown in December 2007 in a stoppage defeat by Anne Sophie Mathis. In all, she fought 39 times, with 28 wins.

Retirement came in December 2008, a year after she was awarded an MBE for services to boxing.

But the respect she was finally earning could not prepare her for what came next - the really dark times of not knowing how to live your life after giving up the thing you loved doing.

And also confronting the issues within, like the Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), for which Couch was eventually diagnosed in 2019 and now receives medication.

She still loves boxing, but from a distance.

"I know for a fact that mental health is a massive problem in boxing," Couch says. "It's just terrible. There are kids out there, professional boxers today and they don't even know, because I never knew, and my friends never knew.

"There are too many chauvinists, especially in the boxing world. I think that the girls need to be watched and monitored, asked if they are OK. Even if I had somebody to pick up the phone to, to ask a question and get an honest answer, that would have made a massive difference to me.

"I'm quite on the ground with ex-fighters. I visit a lot of them in prison, I go and see them on the streets, the drug addicts too. They are all damaged because of boxing, because when they finish, they are just left, there's no after support, there's nothing."

Savannah Marshall and Claressa Shields make history this weekend

On Saturday, Shields and Marshall will take another step forward for women's boxing - and women's sport.

"Up to when I retired, there was this movement happening in women's football and boxing and sport," Couch says.

"It was growing at a rate the TV companies couldn't ignore. They all got involved because they could see the money in it. They didn't do it because they liked women boxing.

"It was all there for the taking. It was never going to happen in my career, but I could see it happening in the future.

"There's still a hell of a long way to go - like in women's football, women's rugby and women's cricket. But women's boxing is on the rise."

Related topics

- Published16 October 2022