Glasgow 2014: Bowling biochemist hoping to inspire Pakistan

- Published

Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games |

Dates: 23 July to 3 August |

Coverage: Live on BBC TV, HD, BBC Radio 5 live, BBC Radio Scotland, Red Button, Connected TVs, online, tablets and mobiles |

Muhammad Shahzad thinks he is 30 years old, but is not quite sure. Calendars were scarce in the rural Pakistani village in which he was born.

So, too, were forenames - it was not until he went to school that his teacher added Muhammad to the family name by which he had always been known.

The disclosures are accompanied by a broad smile. A childhood of such poverty might be embarrassing for some, but Shahzad considers them a vital component of his journey. A journey that will detour briefly from his blossoming career as a biochemist to allow a short stint competing at Glasgow 2014.

Glasgow 2014: Meet the Pakistan Lawn Bowls team

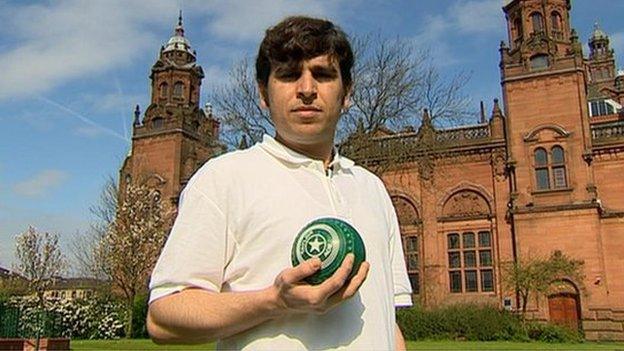

Shahzad is one of his nation's first Commonwealth Games lawn bowls representatives.

Given his country has no history of playing the sport, and Shahzad only took it up as a hobby when he moved to Glasgow as a student about the time of the last Games, expectations of the four-strong team are low.

But with one condition. "They would understand if we did not win a gold medal," he says. "But if we lose to an Indian, we won't be able to go home..."

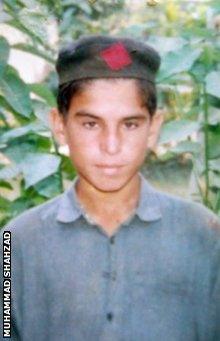

Home for Shahzad is Kalu Khan, a small village in the Swabi district of KPK province. Born in that rural, tribal settlement to illiterate parents whose only means of income was their tobacco crop, he was 16 when he first had his photograph taken and 19 when he saw streetlights for the first time. Until then, he had never been in a city.

Shahzad and his family lived in this shack in rural Pakistan

His parents had to work for four days in the fields to raise the £2 he needed to make that trip to Peshawar to sit his entrance exams for medical college.

"If I showed you a picture of my home, you would not believe it," he says. "You could not imagine how little money we had. My dad is a tobacco farmer and there is only a crop once every year so you either have a good crop or you are short of food.

"But I enjoyed my childhood. Sure, we didn't have gadgets or facilities, but I don't have any regrets except that my grooming and personality might be better if I had gone to a better school. Sometimes people hide these things but I am proud of where I came from and what I have achieved since."

Before bowls | |

|---|---|

Shahzad believes his aptitude for bowls comes from playing a game called Pittu Garam. He says "We would play before and after school because it was free and we couldn't afford to play cricket or hockey. My mum would make me a ball out of old cloth, with which you have to hit a pile of small rocks that have been piled up by the other team." |

Little wonder. After being enrolled in school by his teacher cousin - "I started when people born at the same time as me did; that's how I know how old I am" - Shahzad shone, securing a scholarship and becoming the first person from his community to earn a place at college.

He subsequently qualified as a medical dentist before turning his attention to biochemistry and agreeing a bond with the Pakistani government that enabled him to study for a PhD at Glasgow University.

Such successes mean he is now a role model for the people of Kalu Khan - 15 other children have followed his journey to medical school - and he sends back money every month to his parents, as well as supporting orphans and the local 1600-pupil school.

Shahzad had his photograph taken for the first time when he was 16

"My flatmates are from good families in Pakistan," he explains. "They go to the shops and buy a shirt maybe for £25 and wear it only once but for that money I am helping four or five kids for a whole year at home. My parents work for weeks to earn £25 but I can spare that and it means that kids can get an education and that can change a whole community."

Given the way it has suffered in recent years, his community needs all the help it can get.

Shahzad's childhood - in a region that borders and shares a language and culture with Afghanistan - was played out against a backdrop of what happened following the attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001. About 20 of his friends and members of his extended family were killed during the so-called War on Terror., external

"After 9/11 it was bad," he recalls of growing up less than 100 miles from the border. "My people suffered but it was nothing to do with us - if you ask my dad who is the president or prime minister of Pakistan he would not know.

"Kabul is near us and I remember hearing of an American soldier who showed a picture of New York's World Trade Center Twin Towers to people and they had no idea what it was. They thought it was Kandahar."

His selection for Glasgow 2014 was fraught. The Pakistan Olympic Committee had never heard of bowls when Shahzad first contacted them in 2013, but eventually relented to his lobbying and agreed to enter him.

Subsequently, they have also selected two Glasgow restaurateurs - Qureshi Ayub 'Chico' Mohammed and Ali Shan Muzahir, both of whom moved to Scotland as children and play at district level - as well as a Pakistan-based novice.

"I sometimes think 'what am I doing?' because people back home expect a lot from anyone who is representing Pakistan," says Shahzad, who will begin his campaign against Fiji's Samuela Tuikiligana on Sunday. "I owe a lot to my country because they raised me from nothing. That makes me very proud to wear that flag on my chest."

After Glasgow, the terms of his bond dictate he must return to Pakistan to take up a post as a professor at a medical university. That, though, will not mean the end of his bowls career, with Shahzad keen to introduce the sport to his homeland, even if it might cost him his place in the team for Australia's Gold Coast Games in 2018.

Untapped talent | |

|---|---|

"There are so many kids from my area who could be world-class athletes. We swim in one of the most dangerous rivers in the world every day so, if we can do that, how well can we swim in a pool when we don't have to avoid rocks?" |

"If I can convince my university to have one green, we can really develop bowls," he says. "A huge chunk of the world's population is in India and Pakistan so if they get interested, it changes everything.

"In hockey, you have to support 16 players to win one gold medal; in cricket you need a team to win matches; but in bowls you only need to support one person to win a gold medal so it makes so much more sense. Why not support 10 and maybe get five medals?

"Maybe I'm not one of them but it would be worth it if it means I have inspired other people."

- Published23 July 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published16 July 2014