Boycotts and Broken Dreams: The 1986 Commonwealth Games

- Published

Liz Lynch - now McColgan - won gold at the 1986 Commonwealth Games

Twenty-eight years ago, swimmer Annette Cowley went to the Royal Commonwealth Pool in Edinburgh to watch a Commonwealth Games race.

It was a race she desperately wanted to take part in, a race she could have won. But she was banned for one reason. She was South African.

A day before the competition - on 24 July, 1986 - Cowley was escorted out of the athletes' village, forbidden from competing for England after a last-ditch court appeal failed.

Cowley's story is revealed in a BBC Scotland documentary, Boycotts and Broken Dreams: The Story of the 1986 Commonwealth Games, which explores a Games marred by politics but remembered for sporting triumphs.

"It was a pretty unique situation and watching my race was very hard," said Cowley.

"Especially because I knew I could have won that race and the time that I did at the trials was actually faster than the girl who won the race from Canada."

Annette Cowley was banned from competing at the Games only hours before she was due to race

Jane Kerr won the 100m freestyle in 57.62 seconds. Cowley qualified with 57.51.

Along with South African runner Zola Budd, Cowley was banned from competing for England by Commonwealth officials on 13 July on residency grounds.

It was an apparent move to appease African nations threatening a boycott over Margaret Thatcher's refusal to impose sanctions on apartheid-era South Africa.

It didn't work. In the end, 32 of the 59 eligible nations withdrew.

The 1980s was a time when South Africa's sports stars were banned internationally because of their government's policy of racial segregation.

Frustrated, Cowley - who has an English mother - took the opportunity to race for England at the Games. Her last-minute ban did not just affect her swimming.

A private person who became the centre of a media storm, Cowley recalls searching her room at the athletes' village for any hidden cameras and turning her back to other restaurant customers in fear of being recognised.

Cowley thought her chance had finally arrived when South Africa was welcomed back into the fold for the 1992 Olympics.

Despite clocking some of the best times of her life, selectors decided not to take her as she had already represented England.

"I guess South Africa won," she reflects. "The people of South Africa won in the end because the sanctions being imposed or us not being allowed to compete, it was part of making change in this country."

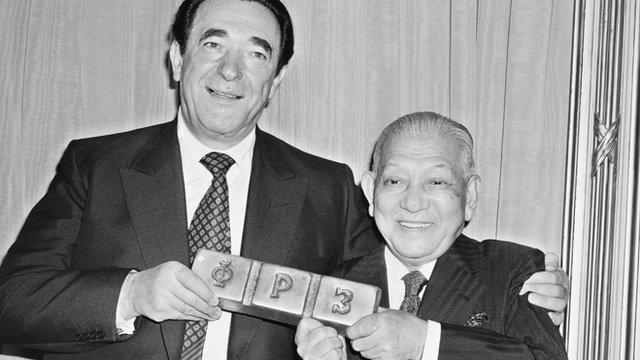

Bermudan swimmer Victor Ruberry: "We felt that we were pawns, that we had no say in any of this."

Cowley was not the only swimmer who was affected by the 1986 boycott.

Bermudan swimmer Victor Ruberry remembers talk of his Caribbean nation boycotting the Games before he arrived in Edinburgh.

On the day Cowley was marched out of the athletes' village - the same day as the opening ceremony - the Bermudans still had no idea if they would be competing.

The country's leader John Swan gave his support to the team. They frantically got dressed into their uniforms, including their Panama hats, and rushed to Meadowbank Stadium.

Having missed their slot, they marched on just before the host nation and received one of the biggest cheers of the night from Scottish fans facing a Commonwealth Games taking place without half of the Commonwealth.

Ruberry was not there. He was hoping to swim in the 100m breaststroke the following day.

Team manager John Morbey came into his room at midnight to finally confirm he would be competing. By the time he had reached the pool, Ruberry knew it was all in vain as Bermuda would join the boycott.

Ruberry was disqualified for keeping his head under water at the end of his race.

He said: "There's a ritual that swimmers go through before competing. They shave down their body in preparation.

"I remember sitting in the bathtub…I was in total disbelief, and then we heard that we're probably going to pull out anyway and it was just it was a bit of a farce. As far as being focused for the competition it was kind of like 'what's the point?'"

The Bermudans decided to protest by hanging bed sheets with 'Bermuda wants to stay, don't penalise our athletes' out of their windows.

Ruberry added: "We felt that we were pawns, that we had no say in any of this, yet we were the ones who'd spent our lives, our money, preparing to represent our country and then all of a sudden we were being pulled out."

Liz McColgan - then known as Liz Lynch - was the star of the 1986 Games for Scotland

The 1986 Games did provide some memorable moments in British athletics history.

For Scots, it was all about a young lady from Dundee.

Brought up on the tough Whitfield area, Liz Lynch left school aged 16 and worked in a jute factory.

Her running coach Harry Bennett sat her down and told her she could be a world-class 10,000m athlete.

She set the 1986 Games - the first time the sport would be introduced at the Commonwealths - as her target.

The young hopeful moved to Alabama on a scholarship and trained away from the spotlight.

When her time came, she was an unknown - and her nation's last hope of an athletics gold medal.

In the race, she opened a large gap between her nearest challenger and the crowd could sense victory.

"It was kind of a two-lap victory run," said the athlete, today known as Liz McColgan.

"The whole of the stadium... it just got louder and louder every step you took."

For McColgan, it was a great moment for her family.

She said: "My dad had this thing in his head that he was a jinx if he watched me running. When I was running the race, he actually left the stadium.

"And then I think either my mum, or an aunt, went and shouted to him and said, 'you need to come and see this because she's winning it', so he actually did come back in.

"My dad's no longer with me, and it really brings home just how proud he was. He just kept repeating to me all the time, 'you did it, you did it. My wee lass has done it'."

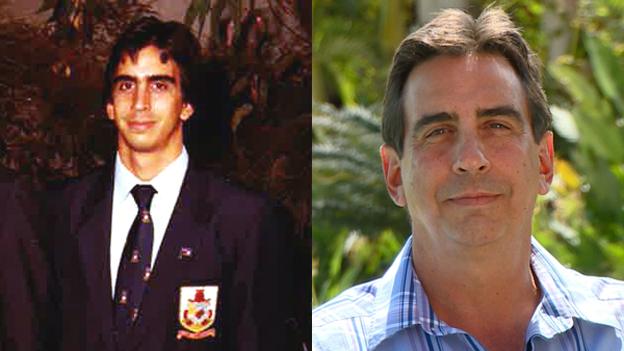

Tessa Sanderson, pictured in 1985 and today

Another British favourite who remembers the 1986 Games fondly is Tessa Sanderson.

Javelin in the 1980s was dominated by Olympic champion Sanderson and fellow English star Fatima Whitbread.

In the summer of '86, it was a showdown and the crowd knew it.

Sanderson was born in Jamaica, one of the nations that boycotted the Games. Her focus was on beating her great rival.

"We, I'd say, set javelin alight and it was great to have that rivalry," said Sanderson.

"You want what they want, or they want what you've got."

Whitbread's huge throw of 68.54m made Sanderson think she "was dead". But the competition wasn't over.

Sanderson added: "It's getting up, proving your worth, focusing again and getting yourself together.

"I launched my javelin. It felt good again and it was the winning throw. You know what was brilliant? The roar of the crowd."

That sort of cheering for British athletes is sure to be heard at Glasgow 2014 venues, the first time the Games has returned to Scotland since 1986.

Sports fans just want a repeat of scenes such Liz Lynch's victory and the Sanderson/Whitbread duel.

For some, though, Scotland's last Games leaves a bitter taste.

- Attribution

- Published17 July 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published16 July 2014

- Published25 April 2014

- Attribution

- Published7 March 2013