The Commonwealth Games - special because they're unique

- Published

- comments

What started under perfect blue skies ended, more appropriately for a city nicknamed Rain Town, with torrential storms.

The 11 Glaswegian days in between were similarly in character - sometimes noisy, sometimes controversial, but seldom dull.

Commonwealth Games often begin as apologetic events. There is as much talk about what they're not - principally the Olympics, but also uniformly world class, or the most important event in that year's sporting calendar - than what they could be.

For them to feel successful they need three things: big names, big performances and big crowds.

Glasgow had all three. In doing so it confirmed something else about the Commonwealth Games: that what makes them special is precisely the fact they aren't like anything else.

So it was that the most memorable performances came as much from unknowns as the superstars. For every gold medal won by Olympic champions such as Kirani James, Alistair Brownlee and Anna Meares, new names emerged who could only have been brought forth by a Commonwealths.

There was 16-year-old gymnast Claudia Fragapane - 4ft 5in, hoping merely to make a few finals, leaving as the first Englishwoman to win four gold medals at a single Games in 84 years.

Fragapane became the first English woman to win four gold medals at a single Games in 84 years

There was Ross Murdoch, overshadowed by poster-boy favourite Michael Jamieson before their 200m breaststroke final, a new Scottish hero after it, having not only snatched gold but done so by improving his personal best over the day by six seconds.

No wonder he swore afterwards. And there was rhythmic gymnast Frankie Jones, almost singlehandedly dispelling the pre-Games gloom about Wales' medal prospects by winning five of them on her own and another as part of the team, which won silver.

Sometimes there were wild mismatches. That's what happens when 71 nations and territories of vastly contrasting size and wealth come together.

There were also great contests. South Africa handed New Zealand their first defeat in Commonwealth rugby sevens. Australia's women stole hockey gold from England by equalising in the last 10 seconds and then polishing them off on penalties. A far smaller distance separated gold and silver in the men's 10,000m won by Moses Kipsiro than in the 100m strolled by Kemar Bailey-Cole.

Neither were the outstanding performances reserved for gold medallists.

Final medals table | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Country | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total | |

1. | England | 58 | 59 | 57 | 174 |

2. | Australia | 49 | 42 | 46 | 137 |

3. | Canada | 32 | 16 | 34 | 82 |

4. | Scotland | 19 | 15 | 19 | 53 |

5. | India | 15 | 30 | 19 | 64 |

12. | Wales | 5 | 11 | 20 | 36 |

17. | Northern Ireland | 2 | 3 | 7 | 12 |

27. | Isle of Man | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

The loudest noise of the Games came when Hampden Park roared Lynsey Sharp to 800m silver after she had spent the previous night in the clinic in the athletes' village, drip in arm and vomit in mouth.

A day later, England's Jo Pavey fought her way to 5,000m bronze less than 10 months after giving birth to her second child. In a month's time she will turn 41.

A Commonwealths can sometimes feel like the FA Cup to the Champions League that is the Olympics - bolstered by its long history as much as its future, defined by the quirky and the outsider, weakened by big boys putting out weaker teams.

Glasgow had its fair share of unlikely underdogs. Kiribati teenager Taoriba Biniati had never been in a boxing ring before arriving to fight in Scotland. Her national boxing club consists of a punch bag hanging from a breadfruit tree.

Kenya's Vincent Onyangi had never swum in open water before diving into Strathclyde Loch for the triathlon. Twenty minutes later he was bobbing around doing breaststroke while the leaders were onto their bikes.

It also had its tear-jerkers: Scotland's Euan Burton coming out of retirement to fight his way to judo gold, two years and two weight categories on from losing in his first bout at London 2012; Jazz Carlin becoming Wales' first female swimming gold medallist in 40 years, having missed the Olympics through illness; 13-year-old Shetland islander Erraid Davies, trained in a 16m pool, winning SB9 100m breaststroke bronze and celebrating with the best smile of the fortnight.

Her fellow teen, Nigerian weightlifter Chika Amalaha, provided one of the darker moments when a failed drugs test led to her being stripped of her 58kg title. Former 400m world champion Amantle Montsho was another thrown out of the Games for doping. Welsh team captain Rhys Williams failed to even make it to Scotland after news of his own positive test at the Glasgow Grand Prix on 11 July.

For the home nations it has been a happier time.

Paddy Barnes successfully defend the light-flyweight title he won in Delhi four years ago

In going from third on the medal table in Delhi four years ago to the top in Glasgow, England ended as the most successful nation at a Commonwealth Games for the first time in 28 years.

Scotland's biggest team secured their best medal haul, Northern Ireland's brilliant boxers propelled them to new heights. Wales, with Geraint Thomas's road-race gold on the final day a fitting finale, overcame a series of big-name withdrawals to sprint past their previous best of 31 medals.

How good was the overall quality? More than 140 Commonwealth records were broken in Glasgow. The record number of Para-sports events integrated in the programme was very welcome.

Equally there were signs that the financial clout of the richest nations is making some of the competition worryingly uneven.

At the 1990 Games, to give one example, home nations won four boxing golds. Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria all won two apiece. Even in 2002, Nigeria, Pakistan, Zambia and India all won golds, while home nations won three.

Glasgow 2014 in numbers | |

|---|---|

Almost 3.5 million people passed through the city's Central Station | More than 50,000 cuddly Clyde Mascots were sold |

1.2 million tickets were sold | An estimated 100 tonnes of fruit and vegetables were consumed |

171,000 people attended the Rugby Sevens - a record for the sport | 15,000 Clydesiders volunteered at the Games |

Now, with high-performance centres in Ireland and Britain backed with serious resources, those former strongholds are struggling to keep up.

England, Scotland and Northern Ireland won nine boxing golds between them in Glasgow. Not one African or Asian country won a title. It was the same story in cycling, gymnastics and triathlon. Even the Friendly Games require competition.

They also require generous hosts, and in that Glasgow was outstanding.

If Delhi was memorable mainly for the fact that few athletes turned up and were watched by even fewer, Glasgow filled stadiums and rattled eardrums.

Approximately 1.2 million tickets were sold, while 171,000 attended the rugby sevens at Ibrox, a new record for the sport. Hampden Park was a sell-out even for morning sessions. Only London 2012 of recent big athletics meets can also boast that.

The enthusiasm was unrelenting. On the first full morning, almost the entire stadium stayed to watch the latter stages of the decathlon shot put. This just doesn't happen. Neither does a women's discus final usually bring the same roars as a sprint final. Hampden managed both.

Getting there and back could be a pain. Long queues for trains at Glasgow Central station and longer waits for shuttle buses meant some ticket-holders missed sessions and connections. En masse karaoke sing-songs to the Proclaimers - the constant soundtrack in every venue - ensured the atmosphere was seldom marred.

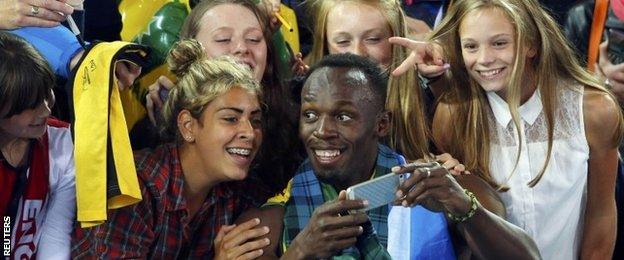

Bolt turned up to make sure no high five was left hanging or selfie left unfilled

It all made you wonder why the Diamond League two-dayer at Hampden last month took place in front of three empty stands. If Glasgow turned out in force for some world-class athletes, why did it not bother when there were many more?

Maybe this is the way it is post-2012: as much about "I was there" as "So were X, Y and Z". Less important than the quality on display is the fact that you were part of it.

And part of it Glaswegians were, as 15,000 volunteers gave up their time and holidays to direct, advise, wave giant foam hands and sometimes just smile. It gave venues a convivial feel and the city a sense of enthusiastic unity, even as other residents struggled to see what benefits their £563m outlay had brought them.

It meant too that the Games, something of a sickly old man after Delhi, will head to Australia's Gold Coast in 2018 reinvigorated and revived.

Beyond that their fate is less certain. But Glasgow, to the Commonwealth movement's long-term gratitude, has played its part.

"In my view, they are the standout Games in the history of the movement," said Commonwealth Games Federation chief executive Mike Hooper. Such praise is as much a tradition of the final day as the closing ceremony. It is also more than empty hyperbole.

The final word, fittingly, should come from the Games' biggest star.

Usain Bolt looked like he might not make it to Glasgow. When he did, he found himself having to deny newspaper reports he had described the city in unflattering terms.

By the end - dancing round Hampden to the Proclaimers, completing his lap of honour after anchoring the Jamaican quartet to sprint relay gold in a tartan tam o'shanter, stopping again and again to make sure no high five was left hanging or selfie left unfilled - both city and athlete were united in admiration and exuberance.

"The people make a Games a Games, and the people really came out and supported," said the incorrigible showman afterwards.

"The stadium was always full, the energy was always up. For me that's a Games. Everything was perfect."

- Published4 August 2014

- Published3 August 2014

- Published2 August 2014

- Published3 August 2014

- Published1 August 2014

- Published30 July 2014

- Published24 July 2014