Ashes 2013: Australia's batting - why is it in crisis?

- Published

- comments

The irony was lost on no-one.

Just as the Lord's ground staff were sweeping up the entrails left over from Australia's latest humiliation in the Test arena, Mike Hussey was stepping out of a shiny black helicopter in Sydney's Olympic Stadium to trumpet his transfer to a new franchise in the Big Bash League.

The timing was awkward for two reasons. For many cricket fans and pundits, Australia's expanding Twenty20 competition is directly responsible for the Test team's declining standard, which had just been so brutally exposed as England took a 2-0 Ashes lead.

And secondly, the appearance of Hussey as a poster boy for the competition was a stark reminder of what Australia have lost and seem incapable of finding again - a natural-born batsman capable of playing the type of innings that alters the course of a Test match.

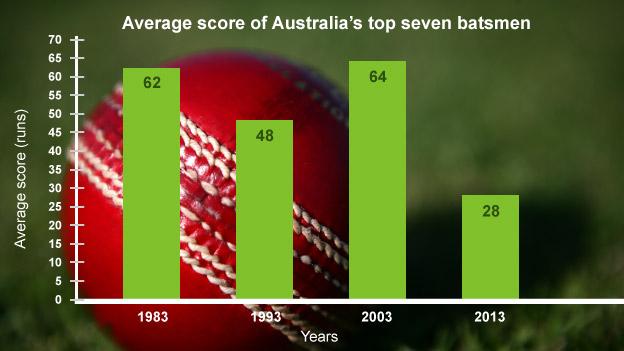

The average scores of Australia's top seven batsmen every 10 years since 1983

Since Hussey followed Ricky Ponting into international retirement in January, Australia have played six Tests and lost all of them, with captain Michael Clarke - the one remaining world-class batsman in the tourists' line-up - posting their only century, in a defeat by India in Chennai.

In 2013, 15 different players have featured in Australia's top seven and scored runs at an average of 28.31 per man. A snapshot from previous decades puts that figure into context: in 1983, Australia's top seven averaged 61.82; in 1993 47.62; and in 2003 63.61.

With the third Ashes Test starting at Old Trafford on Thursday - a match they must win to have any chance of regaining the Ashes following consecutive series defeats - Australia's batting is in crisis.

The production line that turned out Allan Border, Steve and Mark Waugh, Ponting and Clarke, David Boon, Mark Taylor, Matthew Hayden and Hussey, has seized up and is showing little sign of sparking back into life.

But what are the root causes of a dramatic decline that is helping serial victims England become the bona fide bullies in Ashes cricket?

In the short period between the bails being removed at Lord's and Hussey's chopper coming to rest on the Sydney outfield, a missive from Cricket Australia landed in inboxes announcing the extension of next season's Big Bash from 44 to 58 days.

The Twenty20 league will enjoy pride of place at the peak of the Australian summer,, external with the first-class Sheffield Shield tournament squeezed in at either end.

"The Big Bash is becoming such a focus of the season," said veteran Australian commentator Jim Maxwell, who is covering the Ashes for BBC Test Match Special.

"I can't see how that's a good thing for the development of our first-class players, but that's the commercial reality. The talent pool is suffering because of the kind of cricket we are playing."

Former Australia fast bowler Jeff Thomson, once a brutal exploiter of England's batting frailties, was a horrified spectator at Lord's as Australia crumbled to 128 all out.

In an embarrassing afternoon session on the second day, which may well have sealed their Ashes fate, several batsmen brought about their own downfall by trying to take on the England bowling. Thomson believes many were still operating in Twenty20 mode.

"They play cricket like they don't respect bowlers," Thomson, who took 200 Test wickets between 1973 and 1985,, external told BBC Radio 5 live. "They don't adjust to pitches. They go out there and they are used to a certain type of game and they start going at them hard from the first ball."

Twenty20 cricket is distorting players' priorities as well as their techniques.

When the Big Bash League was launched in 2011, each of the eight franchises was permitted to spend up to AU $1m (£602,000) on player salaries for the six-week event, while the contract pool for the six Sheffield Shield state teams was reduced from AU $1.5m to AU $1m.

Throw in the riches on offer in the Indian Premier League - all-rounder Glenn Maxwell was famously given a $1m (£650,000) contract, external by the Mumbai Indians before he had played a Test for Australia - and you begin to see why players are losing motivation for the longer forms of the game.

"I can't help but think if I was a young guy at 14 or 15 wondering 'what am I going to do', I'd be thinking 'yes, I want to play for Australia, but boy I want to play that T20 stuff'," said former captain and opening batsman Taylor when he was reappointed to the Cricket Australia board in June. "That looks like a lot of fun and there's good money in it."

Hayden, Taylor's successor at the top of the order, has a different take on the demise of Australia's Test batting.

In an argument echoed by current batsman Usman Khawaja, external as he sought to explain the Lord's debacle, Hayden claims a marked deterioration in Sheffield Shield pitches is making it difficult for young batsmen to develop the skills required to build long innings.

"We used to have superb first-class conditions in Australia, but there has been a real focus on having pitches that produce results," Hayden, who scored 8,625 runs at 50.73 in 103 Tests,, external told BBC Sport.

The decline in the number of centuries scored by Australia batsmen is clear

"Batsmen have been performing miserably as a result. Have a look at a venue like Tasmania where there are quite a lot of young, quality batsmen, but the conditions are so tough. They have been fighting through tree tops to get to their bowling marks."

Hayden's theory is borne out by the statistics for last season's competition, which show that teams were bowled out for fewer than 200 30 times in 31 matches, while no batsman made it to 1,000 runs for the fourth year in a row.

The identity of the man who came closest to reaching that mark, however, strikes at the heart of the problem facing Australia's selectors.

Ponting, in his final season of Australian first-class cricket, was named Sheffield Shield player of the year, external after scoring 911 runs for title-winners Tasmania at an average of 75.91.

It was a telling reminder that the very best batsmen can succeed regardless of the conditions.

Having excelled in school and grade cricket, Ponting made his first-class debut for Tasmania at the age of just 17 in 1992 and was called up to the Australia Test side three years later.

Two decades on, Australia's hopes of unearthing another Ponting are being hampered by the growing popularity of other sports.

Figures in the Australian Sport Commission's 2010 Exercise Recreation and Sport survey, external show that while participation in organised cricket grew by 14% between 2002 and 2010, the number playing Aussie Rules Football increased by 55%, touch football 33% and football 27%.

Writer Jarrod Kimber: Australians have more things to worry about these days

In 2002, 327,000 Australians aged 15 or over played organised cricket, compared with 289,000 in Aussie Rules. Eight years later, cricket had 372,000 participants, but the figure for Aussie Rules had surged to 447,000.

"Your number one athlete has more choice now than there was 20 years ago," former Australia captain Ian Chappell told BBC Sport.

"In the past cricket got a lot of the first-choice athletes. Now you're in competition with the four football codes. Perhaps they're missing out a bit in that regard."

Whatever the long-term cure for Australia's batting ills, be it fighting the Twenty20 takeover, producing batsman-friendly pitches or luring youngsters away from other sports, the Baggy Greens are in desperate need of a short-term remedy.

Somehow, a group of batsmen who have only produced one individual score higher than 54 in the first two Tests have to find it within themselves to compile match-winning totals against an England side sensing the possibility of back-to-back Ashes victories in the next six months.

"There's better cricket in our top order than we have seen," added Maxwell. "We've got to stick with these guys and hope that at some point they improve.

"But at the moment you are wondering, is that going to happen in England? Is that going to happen back in Australia? Is it going to be 10-0, like Ian Botham said?"

- Published23 July 2013

- Published21 July 2013

- Published22 July 2013

- Published21 July 2013

- Published21 July 2013

- Published21 July 2013

- Published21 July 2013