Where does Sachin Tendulkar rank among the sporting greats?

- Published

There is something faintly absurd about journalists ranking the deeds of our finest sportsmen and women: who am I, to whom greatness is a stranger, to judge greatness in others?

And how 'great', really, is someone who happens to have been conferred with the talent of ball control? Nelson Mandela-great?, external Give me a break.

Yet there was lionisation of gladiators in ancient Rome and wrestlers in ancient Greece, suggesting it is inherent in humans to be awed by the athletic prowess of others.

No pub bores back in Neolithic times, but there were probably caves full of blokes arguing over who was the greatest tree-climber ever. Even Mandela, usually taken up with more cerebral matters, admits one of his biggest heroes is Muhammad Ali.

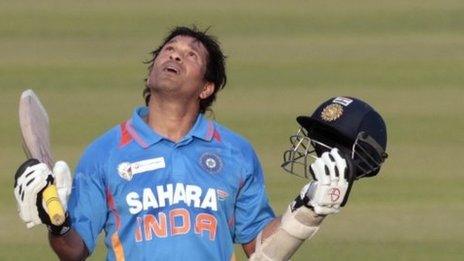

So, let's have it then: as he announces he will retire from cricket next month after his 200th Test, how great is Sachin Tendulkar?

To answer that question, it is necessary to define sporting greatness. Then we must address how closely Tendulkar fits each component part of that definition. Don't worry, this isn't a university thesis, but Tendulkar hagiographies will be everywhere in the coming days and weeks.

When Andrew Flintoff retired from cricket in 2009, external arguments raged in the media and in pubs across the land as to whether he was great or not. Some said not, because the first component part of greatness is cold hard statistics.

In 79 Tests and 141 one-day internationals, Flintoff scored eight centuries and took five five-wicket hauls, and never a 10-for. South Africa's Jacques Kallis, external has to date played 162 Tests and 321 ODIs, scoring 61 centuries and taking seven five-wicket hauls. In addition, his bowling average in Tests is better than Flintoff's (the Englishman's ODI bowling average is, admittedly, markedly lower).

If a great cricketer is someone whose numbers are comparatively better than all or almost all of his contemporaries, then Kallis qualifies. Flintoff does not. Tendulkar, meanwhile, has scored 29 more tons than the next highest century-maker in international cricket, Ricky Ponting, which puts the Indian out on his own. Miles out, in fact, just like Don Bradman's vertiginous batting average., external

Flintoff was a cricketer who occasionally did great things, which is different from being a truly great cricketer. Which takes us to our next component parts of greatness - longevity and consistency of performance.

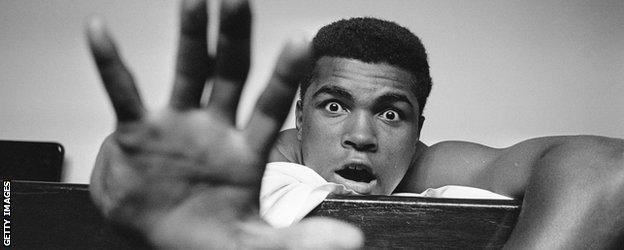

Heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali is considered by many to be the greatest sportsperson ever

To score 100 international centuries, it was necessary for Tendulkar to be at the top of the game for 24 years, which in any sport is extraordinary. In that time, at least until his struggles of the past two seasons, he has suffered nary a blip. He had a rough time in Tests in 2006, but the following year he scored 776 runs at an average of 55.4. Not much of a blip.

Paul Gascoigne had more talent in his big toe than most England footballers playing today. But truly great? It is difficult to countenance the idea - too few highlights, far too many lows.

John Daly, external has won two majors in golf, but only one tournament since claiming the Open Championship in 1995. Does that make him a better golfer than Colin Montgomerie, who has 40 professional wins to his name, but none of them a major? And if so, does it follow that Daly is necessarily a great? Again, many would say no.

Longevity was a big part of Ali's greatness - he won Olympic gold in 1960 and regained the heavyweight world title 18 years later. Mike Tyson,, external past his best at the age of 24, did not even make venerable boxing historian Bert Sugar's all-time heavyweight top 10., external

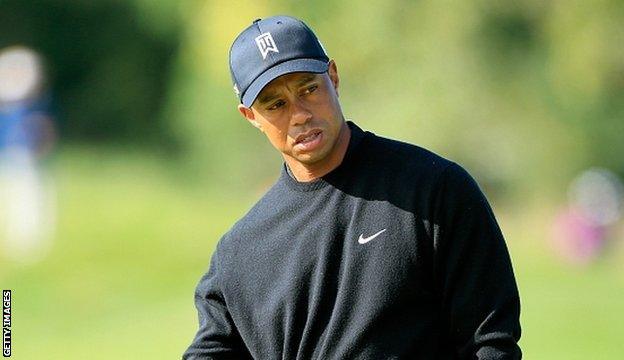

Tiger Woods has come in for criticism for his manners and bearing on the golf course

Sugar, meanwhile, had Britain's Lennox Lewis down at 18 in his list. This is frankly bizarre, but I can understand his thinking: Lewis's achievements, Sugar would no doubt have argued, were diminished by a lack of competition. Competition and rivalry are also significant factors when it comes to measuring greatness.

Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal are considered by some to be the two greatest tennis players of all time, in large part because they have amassed 30 Grand Slam titles between them. But also because they have amassed those titles by having to beat each other on a regular basis.

In Tendulkar's first Test, against Pakistan in Karachi in 1989, the 16-year-old faced fearsome pace duo Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis and he played during the last flourishing of great West Indian quicks.

Against Australia, the world's best team for most of Tendulkar's career, he averaged 45 in ODIs and 55 in Tests. Like Federer and Nadal, he thrived against the best.

Tendulkar 'only' won one World Cup (in 2011) but a better gauge of the greatness of team players is how they perform as individuals on the biggest stage. In that respect, Tendulkar is peerless. In six World Cups, Tendulkar has scored the most runs (2,278), most centuries (six), most 50+ scores (21) and the most runs in a single tournament (673 in 2003).

When it comes to judging greatness, aesthetic considerations are secondary to numbers. But ask a Brian Lara devotee why they believe their hero to be greater than Tendulkar and there is a chance they will mention that majestic cover-drive of his, like honey dripping off the back of a spoon.

Lara, an alchemist like Ali, transformed sport into epic poetry. Tendulkar, meanwhile, dealt mainly in prose. But anyone who fails to appreciate that timed on-drive of Tendulkar's has a small piece of their heart missing, by definition.

Last, it is necessary to look at how Tendulkar went about his business - the manner in which he achieved what he did, temperamentally rather than aesthetically speaking.

Some believe Tiger Woods has tarnished his greatness with his personal travails,, external surly bearing and spitting and cursing on the golf course. And there are those who think Tom Watson,, external for example, is the greater golfer because of his more dignified nature.

Cricket legends rate Tendulkar

Tendulkar is more Watson than Woods. During three decades at the pinnacle of his sport, under the glare of more than a billion countrymen, there has been barely a hint of controversy. Indeed, some would argue he has been a little bit dull, that a bit of off-field strife or outspokenness would have made him a more engaging figure.

But it is impossible to imagine the pressure Tendulkar was under. As the signs at his home ground in Mumbai say: "If cricket is a religion, then Sachin is God." The poor bloke had enough on his plate without inviting more attention, and perhaps only Manny Pacquiao, whose fights stop wars in his native Philippines,, external can truly empathise.

Ask a member of England's Rugby World Cup-winning side of 2003 who the most important member of the team was and there is a good chance he will say Richard Hill., external Hill is a bona fide great, but he is fortunate in that he can stroll round his local supermarket and hardly anyone will recognise him.

The true greats - the really, really, really great - transcend their sports, become almost god-like. And gods don't go to the supermarket for their shopping.

Tendulkar, a legend in his own career, is on the top table, up there with Tiger and Michael Jordan and Pele. Not the greatest, though - I'm with Mandela, that simply has to be Ali, the greatest great there has ever been and probably ever will be.

Note: This story, with some changes, originally appeared as a blog in March 2011 on the eve of Sachin Tendulkar winning the World Cup with India.

In a special BBC Radio 5 live programme on Monday 14 October at 21:00 BST, Mark Chapman is joined by BBC cricket correspondent Jonathan Agnew and Indian commentator Prakash Wakankar as they look back at the career of Sachin Tendulkar.

Archive: Tendulkar's maiden ton

- Published10 October 2013

- Published10 October 2013

- Published10 October 2013

- Published10 October 2013

- Published11 October 2013

- Published24 April 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Attribution

- Published24 April 2013

- Published23 December 2012

- Attribution

- Published16 March 2012

- Attribution

- Published16 March 2012

- Published18 October 2019