Jonathan Trott: England batsman plays cricket for fun of the game

- Published

If much of what has been said into stump mics during the past few days has been unpleasant and over-excitable, then the reaction to Jonathan Trott's departure from this Ashes tour with a stress-related illness has been thankfully restrained and sympathetic.

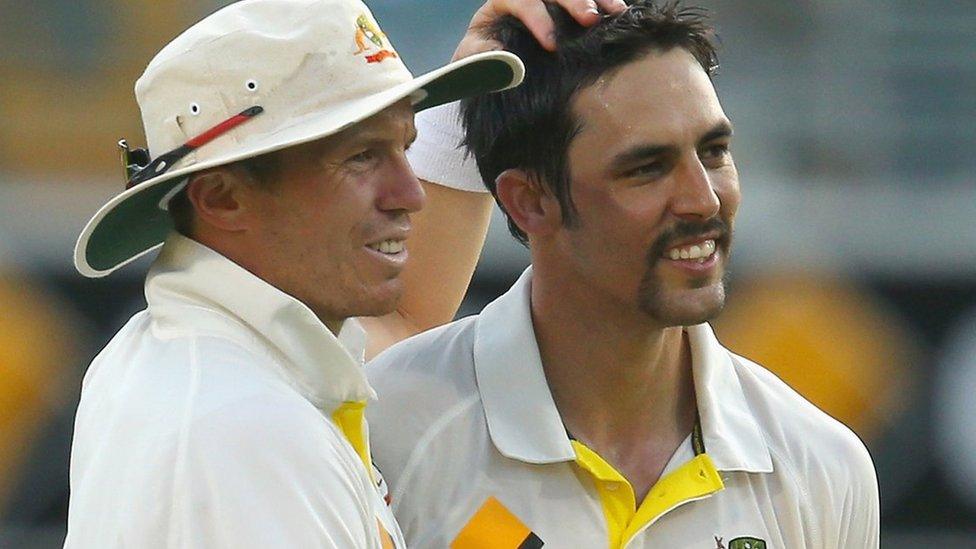

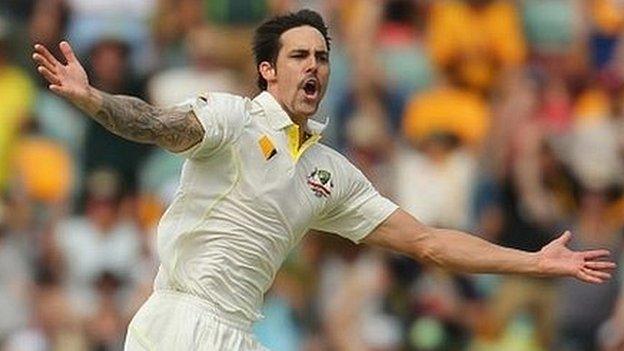

The only indication to those around the tour that anything like this might be about to happen had been the sight of Trott with England team psychologist Mark Bawden as he left the Gabba on Saturday evening, shortly after a technically tortured nine-ball innings had ended with his second dismissal to fast bowler Mitchell Johnson in two days.

But just as Bawden's presence alongside an England player was nothing out of the ordinary - James Anderson, Stuart Broad and Ian Bell have all told me at length about how much and how often they appreciate his input - so should trite explanations of Trott's condition be avoided.

It is a sad truth of mental illness that the sufferer themselves can frequently be unable to explain its origins and hold, let alone those watching on from a distance.

England's management were at pains to stress that this has been a long-term issue for Trott, not something triggered either by his travails against Johnson at the Gabba or David Warner's comments afterwards that he had "scared eyes".

Trott may appear from the outside to be an intense, obsessive cricketer. But he has always relished the on-field examinations he has faced, tried to take pleasure in being tested.

"You've got to be able to enjoy the battle," he told me last year.

"Sometimes you can have a fast bowler taking aim at your head or your feet at 150kph (more than 90mph), and you've got to be capable of dealing with it or you won't survive.

"You need the confidence in yourself to say, 'this is amazing, let's relish it'."

Neither is he the sort of man who is easily hurt by the barbed words of opposition players.

"You get sledged about everything, anything that's a little different," he told me, when we were chewing over the reaction to his famously idiosyncratic habit of repeatedly taking guard.

"If you are out there fielding it's almost like a red flag to a bull. They really go for it. But I don't really care what they think. Everyone's got their ways that make them feel comfortable, and that's the most elusive place to be as a sportsman. Everyone wants to be there."

It is just one of many misconceptions about the 32-year-old. What some interpreted as the fanatical routine of a man lost in nervous compulsion was instead a simple technical trick to get himself in the right position to face the ball.

Ashes 2013-14: Andy Flower explains Jonathan Trott decision

"The scratching the line has come from playing in England and batting out of my crease. I'd find that, on early season wickets, I'd be batting on middle stump when I should have been on leg or middle and leg, and I needed to be sure of my guard.

"It comes from a lot of practice, from working out what suits me best. I find too that the scratching helps me clear my mind. It helps it keep ticking."

Cricket, for Trott, has been about enjoyment rather than obsession. He genuinely cannot tell you his Test average, or how many Test runs he has scored.

When he made his England debut, against Australia at the Oval in 2009,, external his disappointment in getting out in the first innings was because he was savouring the experience so much.

"I was really upset because it was the most fun I'd ever had playing cricket - 35,000 people cheering every run!" he told me.

This, sadly, is not the first time that an England cricketer has had to leave a tour with stress-related condition. Marcus Trescothick left the 2005-06 India tour, external and the 2006-07 Ashes tour, external of Australia; left-arm spinner Michael Yardy flew home from the 2011 World Cup., external

Each deserves our sympathy rather than our opprobrium. For the strange bubble that is an international cricket tour, several time zones and thousands of miles from friends and family, is no place for someone struggling with such an illness.

Few sports leave an individual as exposed as Test cricket. While it is nominally a team sport, all the confrontations are on a purely individual level. There is no hiding place, no passing of responsibilities nor chance to be carried by team-mates.

If you are in both Test and one-day teams, as Trott has been since his England debut four and a half years ago, you live the life of a strange nomad, staying in pleasant hotels but never entirely free to do what you choose or go where you would like.

Professional male sport is still in the early stages of learning that admitting weakness is not necessarily a bad thing. You are not somehow less of a man if you suffer from mental illness. You are just a man.

Trott has found great joy in his young family of wife Abi and three-year-old daughter Lilly. When he scored his match-winning century at the MCG on his first tour of Australia, he carried his then two-month-old daughter to the crease when play had finished "just to show her where daddy had been".

As a child himself he was totally immersed in cricket. At his father's sports shop in Cape Town he would sit out the back, knocking in bats and changing grips. His reward would be a set of gloves and bat of his own.

His dad would coach him after hours; his mother, a hockey and softball international, would work on his hand-eye coordination.

"I probably had something of an abnormal childhood, because everything was about sport," he told me.

"Having a family has definitely changed me. The emphasis on yourself and cricket doesn't go out of the window, but it becomes a bit less.

"Sometimes you can get wound up and take things a little too seriously. Cricket is hugely important. It's my job and something I really take pride in, but you take pride in being a husband and father."

There are practical questions now for England about how they replace him in their top order. There will be comparisons drawn too with the disastrous Ashes tour of 2006-7, when Trescothick's departure was one of many off-field problems that beset the party as they slumped to that 5-0 defeat., external

For now those are less important than the health of Trott himself. Supporters of both England and Australia should wish him well.

- Published25 November 2013

- Published25 November 2013

- Published25 November 2013

- Published25 November 2013

- Published24 November 2013

- Published24 November 2013

- Published24 November 2013

- Published23 November 2013

- Published22 November 2013

- Published5 January 2014

- Published2 February 2014

- Published18 October 2019