Mitchell Johnson: Fear & brilliance of retiring Australia fast bowler

- Published

- comments

Johnson announced on Tuesday he was retiring from all forms of international cricket

Mitchell Johnson's cricketing career might be remembered for several stellar achievements.

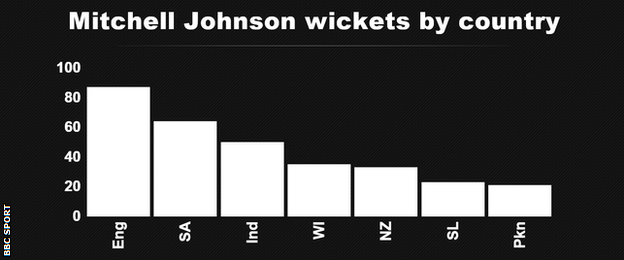

For 313 Test wickets at a strike rate better than Shane Warne or Glenn McGrath, for defining one Ashes series with his misery and another with his brilliance, for reviving both flat-out fast bowling and the handlebar moustache that once characterised its greatest exponents.

You might remember him for that song; not since Paul McCartney released the Frog Chorus had a simple tune wrecked a reputation so effectively. You might remember him for the remarkable renaissance that followed, one of the great redemptive stories in any sport.

Or you could encapsulate it all in a single word: fear.

Mitchell Johnson was emotional as he acknowledged Australian fans after his final game

Fear struck into the world's best batsmen - not just of losing their wicket, but of losing teeth and solid fingers. Fear in the tail-enders left exposed by his destruction of the top order, visible on their faces as they backed away or ducked with eyes squeezed shut. Fear in the hearts of opposition supporters, silenced by his snorting charges to the wicket, cowed by the sight of stumps being splattered and their key men trudging off.

And, a lot of the time, fear in Johnson's own mind - of what might come out of his left hand next, of when the mojo might mysteriously leave him again, of when his fragile body might lurch from slick machine to broken-down wreck.

When it worked, it was like no-one else. In the winter of 2013-14 Johnson's 37 wickets at an average of 13.9 were not just the decisive factor in Australia winning back the Ashes 5-0. He dismantled a team and ended careers.

Because it was Johnson, it was almost impossible to see coming. His preceding act in an Ashes series had lasted precisely one ball, bowled for a golden duck at Sydney as England sealed their historic 3-1 series triumph,, external serenaded to the crease by 20,000 Englishmen leaning to their left and their right, laughed all the way back to the pavilion.

Mitchell Johnson had a love/hate relationship with England fans, who enjoyed mocking him when he was dismissed

Even at the start of his great series there were few signs of what was to follow. His first three overs in Brisbane went for 15, his first six went for 32, often a long way down leg-side.

Then in blew a storm that would rage across the land for the next six weeks.

Four in the first innings at the Gabba, five in the second. Five more English first-innings wickets in three overs in Adelaide, eventually six for 16 in 26 balls including a triple-wicket maiden and two separate hat-trick balls.

Six more scalps in Perth, 5-63 in the first innings in Melbourne and 3-25 in the second; another six on the site of his great humiliation in Sydney. All of it hostile, whether aimed at throat or toes, all of it unstoppable.

Almost as stunning as the spells was that they kept coming, for the one firm rule in Johnson's career had always been to expect the unexpected.

His greatest strength was also his great downfall: that javelin-thrower's left-arm delivery, body going one way and arm the other. It gave his bowling a pace and trajectory that shocked modern batsmen raised on accurate seamers and five-day pitches, but left him only the most minimal margin for error.

His only consistency was in being inconsistent. Forty seven wickets at 21 in eight Tests before the 2009 Ashes, match figures of 3-132 at Lord's that summer as England's batsmen took him for six an over. A cumulative 0-170 in the first Ashes Test of 2010, 9-82 in his next Test at Perth, 2-134 in the following match in Melbourne.

Even this summer he was still doing it. In the third Test at Edgbaston, he produced the best two balls of the entire series to see off Jonny Bairstow and Ben Stokes in the same over, yet they were his only two wickets in the match as England took a series lead they would never relinquish.

"There were days when Mitch was as lethal a bowler as any in my experience," his former skipper Ricky Ponting wrote in his autobiography. "At other times, he was so frustratingly erratic and ineffective.

"For someone so talented, such a natural cricketer and so gifted an athlete, I found his lack of self-belief astonishing."

Because Johnson could be as shy and insecure off the pitch as he could be aggressive on it. During the Ashes of 2010 you would see him on flights between Tests looking like a lost child - staring out of windows at the desert below, cut off from the banter of his team-mates, as meek as all around him were noisy.

He once fell out with his own mother so badly that she was excluded from his wedding invites. Even at the height of his powers he preferred the company of his young daughter Rubika to the sponsors' parties and gossip columns enjoyed by his skipper Michael Clarke.

Even the iconic moustache was unintended armour, initially just a Movember charity effort rather than deliberate attempt to remould himself in the image of his fiery predecessors Dennis Lillee and Merv Hughes.

Mitchell Johnson had many confrontations with England players over the years, including this one with Stuart Broad in the Ashes in 2009

Lillee had always seen something outstanding under the introverted exterior, describing him as a "once-in-a-generation bowler" when he first spotted him as a raw 17-year-old kid from Townsville on the Queensland coast.

Not everyone else had the same faith. Four stress fractures of the back put doubt in some coaches' minds. Former Australia coach Mickey Arthur once suspended him for refusing team orders. Ponting could not understand why he could not bowl the long spells he had seen from McGrath.

It was fitting that Lillee led his great regeneration - advising him to lengthen his run-up and increase the hostility. Another Aussie fast bowling legend, Craig McDermott, worked with him daily; Terry Alderman worked on his wrist position; Adam Griffith, his bowling coach at Western Australia, got him running in straighter, staying tall at the crease and remaining high in his follow-through.

Together they transformed a washed-up great wide hope into the best fast bowler of his generation.

England would pay the price. But even in those dark days of that 5-0 whitewash there was something wonderfully thrilling about it all, just as the players eviscerated on that tour - Kevin Pietersen, Jonathan Trott, Matt Prior - have all paid tribute to Johnson in the aftermath.

At his worst, Johnson turned Test grounds into comedy clubs. At his best, he transformed them into gladiatorial arenas: thousands baying for blood, strong men cowering, no-one daring to take their eyes off a single moment. And that fear, thick in the air, there everywhere you looked.

- Published17 November 2015

- Published7 December 2013

- Published15 May 2018

- Published18 October 2019