Women's cricket: Remembering the 1973 World Cup, 50 years on

- Published

- comments

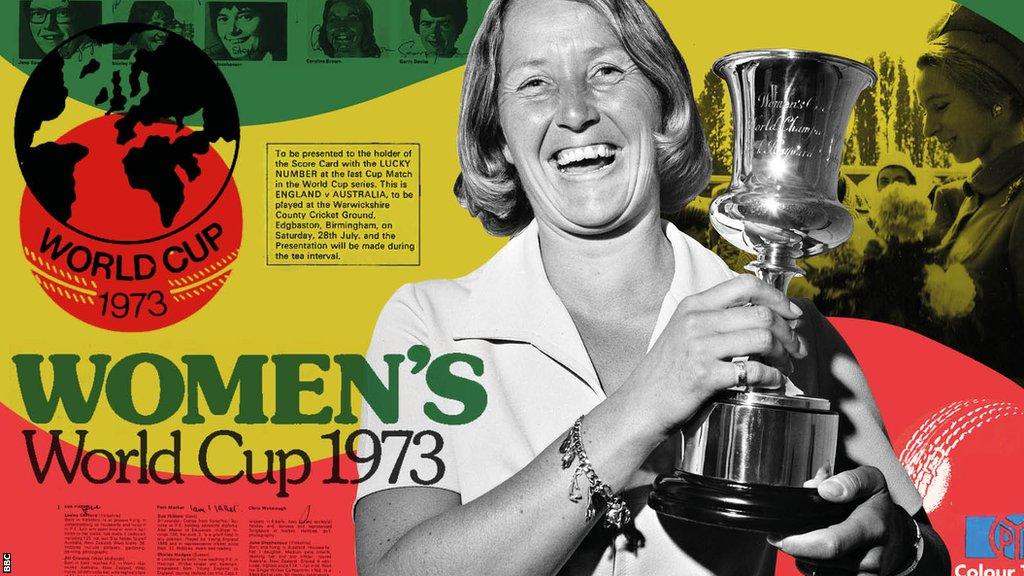

Rachel Heyhoe Flint with the 1973 World Cup trophy

Women's cricket is growing exponentially.

The top international teams are now full-time and franchise cricket has taken off around the world, with the recently completed Women's Premier League paying large sums of money to the top players.

But it's not always been that way.

Today's generation is forever indebted to the women who paved the way, including those who competed in the first ever World Cup in 1973 - which was played two years before the inaugural men's version.

"It was a lot of commitment and of course, we had to return to jobs," remembers England's World Cup-winning wicketkeeper Shirley Hodges.

"One of the players in the tournament was so tired she actually fell asleep at the wheel and only woke up when she hit the crash barrier."

The player was fine but it is a tale that highlights the taxing nature of the tournament.

Hodges adds: "It was utterly exhausting. I remember playing in Bradford and then the next day they wanted me to play for Sussex in Eastbourne against Trinidad and Tobago."

That's a drive of more than five hours after 120 overs in the field.

Personal sacrifice is the tale of all who made the event happen. To fund their cricket in the amateur era, players had to get creative.

"There was no-one giving us things," said Trinidad and Tobago captain Louise Browne. "We set up barbeques and curry-ques - we had to raise money for all of our cricket."

"We did all sorts of things," adds England's Enid Bakewell. "I had potatoes out of the ground, and I used to put a decorating table at the top of the drive and stood there selling potatoes which were cheaper than the grocery store opposite.

"However, in the end, I ran out of the potatoes and had to go and buy them from the grocery store anyway."

Fundraising was one side of the coin. The other was having an understanding employer.

"I was PE teaching at the time," said England player Chris Watmough. "I was lucky I got a job and the headteacher was very supportive."

Meanwhile, England's legendary captain Rachael Heyhoe Flint - later Baroness Heyhoe Flint - not only carried the pressure of organising the team, but had the weight of the tournament on her shoulders.

"You can't say women's cricket and not say Rachael Heyhoe Flint," says Browne. "Rachael was a pioneer. She's gone down in history for what she's done for women's cricket."

After all, the World Cup was her idea...

A life-changing friendship

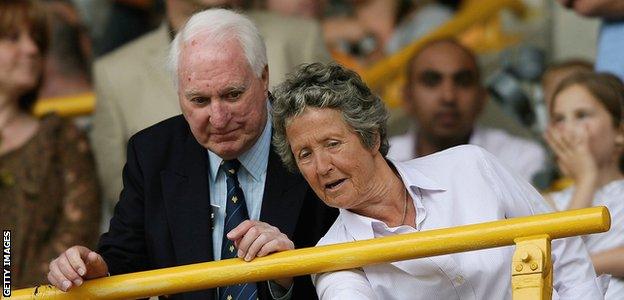

Former Wolverhampton Wanderers owner Sir Jack Hayward and Rachel Heyhoe Flint were the driving forces behind the first Women's World Cup

When Heyhoe Flint was searching for sponsorship for an unofficial tour of Jamaica, she sent a "begging letter" to Wolverhampton-born millionaire Charles Hayward.

Luckily, the letter was passed across to his sports-loving son Jack, who felt compelled by her words and presented Heyhoe Flint with £1,700 to fund the first of two tours to the West Indies.

Then, in 1971 over a brandy and a long evening chatting the night away, the duo came up with the idea of a World Cup.

Infamously, the businessman said "I love cricket, I love women, why shouldn't I sponsor women's cricket?".

Before World Cup planning could get under way, Heyhoe Flint and Hayward required sign-off from the Women's Cricket Association (WCA), a voluntary organisation responsible for the running of the women's game in England between 1926 and 1998.

Hayward made a £40,000 proposal to WCA chairperson Sylvia Swinburne - an offer too good to turn down.

"The tournament definitely got women's cricket on the map," says Megan Lear, "but it just didn't get reported.

"Anything that went into the national print media was only via women's cricket people who submitted it or happened to work for them, as the media never reported on any of the games."

Audrey Disbury was responsible for sourcing the grounds and secured 21 club and 1st XI grounds stretching from Exmouth to York.

Matches in the tournament, which was organised in a round-robin format, were played predominantly on Wednesdays and Saturdays from 20 June to 28 July.

Scripted perfectly, the final match was scheduled as England versus Australia, and it turned out whoever won this final fixture would be crowned inaugural World Cup champions.

Aptly, the de facto final was in the hometown of both Heyhoe Flint and Hayward at fortress Edgbaston.

The teams

All of the players were amateurs, more than 40 years before England's first full-time professional contracts were issued in 2014.

The WCA invited teams that were members of the International Women's Cricket Council, and Australia, Jamaica, New Zealand and Trinidad and Tobago accepted. South Africa, in the midst of apartheid, were not invited.

Also included was an International XI and a Young England side.

On the pitch, England excelled with the bat. As a team they scored 1,055 runs across the competition - over 300 more than second-placed Australia.

Enid Bakewell scored 264 runs, Lynne Thomas 263 and Heyhoe Flint 256 to make up the top three batters of the competition.

Bakewell and Thomas opened together across three matches and the pair posted opening stands of 246, 81, 101 - an average just shy of 143.

In England's first-ever ODI, they set a record opening partnership of 246 against the International XI.

It was a record that would stand until India's Mithali Raj and Reshma Gandhi pipped it by 12 runs against Ireland in 1999.

While England dominated with the bat, the Australians were destructive with the ball.

Their dominant bowling attack, consisting of Tina Macpherson, Sharon Tredrea and Raelee Thompson, was widely feared.

Young England's Megan Lear calls her experience facing the Australians a "good initiation".

"Sharon Tredreu is probably one of the all-time greats," said Lear. "If you compared her with one of today's players, which you can't really do because we didn't have the speed guns, but she would easily be as good as Katherine Sciver-Brunt, she was so quick."

Fast bowler Thompson said: "I never thought back then I was fearsome or that quick, but I must've been.

"I know I certainly hit a few keepers in the face in my time and you don't do that if you're slow."

She's a keeper

England's Shirley Hodges completed eight dismissals, two stumpings and six catches which was the most by a wicketkeeper.

Her biggest moment came in the final match, dismissing Australia's Thompson with a catch described as equally as good as that of her male counterparts of the time.

"One of the finest ever produced by a woman - low and diving to her right in front of first slip - a catch of which even Alan Knott would have been proud," writes Heyhoe Flint in her 1976 book FairPlay.

Downing Street reception

Players from all the teams were invited to a reception at 10 Downing Street

On 28 June, all of the teams were invited to 10 Downing Street for a reception with Prime Minister Sir Edward Heath.

Jamaica's Dorothy Hobson retells a story of mischief and mind games that occurred at the reception.

"[Jamaica all-rounder] Grace Williams had misplaced her dress shoes so she had to put on a pair of sandals," remembers Hobson.

"When we went to the function all the teams were there and they were very happy when they saw Grace's toes had plasters all over them.

"So they were thinking 'OK, she won't be playing tomorrow' but the next day we were playing England and Grace came out and one of the English girls came up to her and said 'you're a damn liar'.

"But we had a good laugh about it - they probably realised they needed to change their batting line-up because Grace really was a good bowler - very fast."

The 'final'

Heyhoe Flint's England side were the winners of the first ever Woman's World Cup

The last match scheduled between England and Australia would determine who would lift the inaugural trophy.

"We got a lot of runs on the board - that was our preferred way, to bat first," said Watmough.

"It felt like we were chasing leather all day," laughed Thompson. "Enid made many runs, they really showed us how to play limited-overs cricket."

It was Bakewell's day. She stood up with both bat and ball, scoring 118 and picking up two wickets.

Player of the match Bakewell was well supported by Lynne Thomas (40) as they once again shared a century opening partnership.

Captain Heyhoe Flint smashed 64 at number three and Watmough was praised for a blistering 32 to set 279-3 from England's 60 overs.

In response, June Stephenson bowled Beverley Wilson (41) and then the run out of Margaret Jennings without scoring soon followed.

Australia struggled to keep up with the required run-rate as England's bowlers impressed.

England dominated by 92 runs and were crowned the inaugural World Cup winners, with Her Royal Highness Princess Anne presenting the Georgian chalice to captain Heyhoe Flint in front of a jam-packed grandstand.