Lance Armstrong: Life ban could be reduced, says Usada chief

- Published

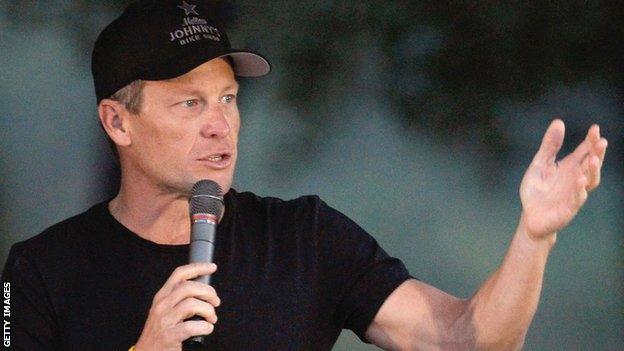

Lance Armstrong was stripped of seven Tour de France titles

Lance Armstrong's lifetime ban from cycling could be cut to eight years, according to the man who played a key role in proving he doped during all seven of his Tour de France wins.

Travis Tygart, head of the United States Anti-Doping Agency (Usada), said such a reduction is "technically possible" should the American, 42, agree to reveal all about his past.

"He's had plenty of opportunities to come in before now and there's no sense that is actually now going to happen," Tygart told BBC Sport.

"We'll see if there is still an opportunity for him to get any reduction."

Armstrong was banned for life by Usada in August 2012 and stripped of the seven Tour de France titles he won between 1999 and 2005.

After repeatedly denying accusations of doping, the Texan finally admitted in an interview with television chat show host Oprah Winfrey in January that he took performance-enhancing drugs during his career.

Cycling's world governing body, the UCI, intends to set up an independent inquiry into doping.

UCI president Brian Cookson is keen the inquiry hears evidence from a large number of people, not just Armstrong, as he attempts to restore cycling's credibility and that of his own organisation, which has faced allegations of corruption.

Tygart told the BBC that it was important for cycling to "unshackle itself from its dirty past for the good of everyone".

I've not been treated fairly - Armstrong

He added: "What's important is this sport moves forward and puts this dark, dirty time period behind it and give clean athletes a chance to be successful."

But he condemned Armstrong for continuing to cast a shadow over the sport, claiming "clean athletes have been hurt" by his failure to speak up.

On Monday, Armstrong told the BBC he would be willing to reveal more about his past as a drugs cheat, but only if he was treated fairly by those investigating cycling's culture of doping.

The American, who pledged to testify with "100% transparency and honesty", argued that some cheats had received "a total free pass" while others had been given "the death penalty".

In an interview with BBC sports editor David Bond, Cookson made clear that Armstrong's ban is a matter for Usada.

"It wouldn't be helpful for me to suggest a length of ban but, if you look at the current rules, Usada could probably look at an eight-year ban," said Cookson.

"If Usada were to agree that, then the UCI certainly wouldn't oppose it but, equally, I'm not recommending that either."

Cookson stressed that Usada, as the sanctioning body, has sole responsibility for deciding whether Armstrong's ban is reduced or not.

"The UCI can't have much impact on his current situation because the sanctions have been imposed by Usada," said Cookson.

"Armstrong needs to be clear with them what his role is, what he can and can't offer to them in terms of substantial assistance to look at whether they can offer him any reductions in the sanctions that he's currently got."

Cookson met with the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) president John Fahey to discuss plans for an inquiry into doping.

Although it will be funded by the UCI, it will be independent of the world governing body and run by a chairman to be appointed in the next few weeks.

The inquiry is expected to start taking evidence in the new year and could run for months.

It is also likely to focus on the years from 1998 onwards, beginning with the period just before Armstrong came to dominate the sport.

"We've got a timeframe in mind as to how far back we go," said Cookson. "That's probably likely to be 1998, which is as good a time as any.

"That ties in with the big controversy at the time, the Festina Affair., external There was an opportunity for cycling to make a new start at the time, which it didn't take.

"I'm not going to rule going back further than that if Wada or others think it's essential or, indeed, if others want to come forward and give evidence about years before that.

"I want it to be relevant to the current situation and help an organisation that provides information, advice and conclusions that we can use to build cycling on to stop those mistakes happening again."

- Published12 November 2013

- Published11 November 2013

- Published24 August 2012