Sir Bradley Wiggins: Tour de France omission 'coolly rational'

- Published

- comments

Wiggins 'gutted' to miss Tour de France

And so what was suspected in cycling's peloton of insiders and whisperers for the past few weeks has escaped into the open: Sir Bradley Wiggins, the most recognisable and popular cyclist the country has produced, will not be part of the biggest party the sport in Britain has ever seen.

For many of those who voted him BBC Sports Personality of the Year in the most spectacular year of sport in British history, for those as charmed by his eccentricities as captivated by his achievements, his likely exclusion from Team Sky's squad for the Tour de France will trigger both bewilderment and surprise.

The three stages of the Tour in England this July represent not only the start of the world's favourite bike race but also a new pinnacle for British cycling, which has scaled so many storied peaks in the decorated decade since the Athens Olympics.

Wiggins became the first British rider to win the Tour de France in 2012

Wiggins is the modfather of this great rebirth: embodiment of the Olympic track gold rush that triggered the founding of a British-based road team capable of winning the Grand Tours; Team Sky's first big-money signing, their great vindication when he became the first Briton to win the Tour de France two summers ago, the nonchalant king of the Olympic time trial at Hampton Court a few weeks later.

His immediate form is not in doubt. He is fresh from winning a gruelling Tour of California, having impressed the cognoscenti with his ninth place at Paris-Roubaix in spring.

Neither is his desire. "I'm gutted not to be there," he told the BBC. "I've worked extremely hard to be there all winter. I feel I am in the form I was two years ago."

But desire, popularity, and past wonders, have little to do with the selection of a Tour team. This is no valediction nor lap of honour. Wiggins's omission is coolly rational in a way that the wider reaction to it may not be.

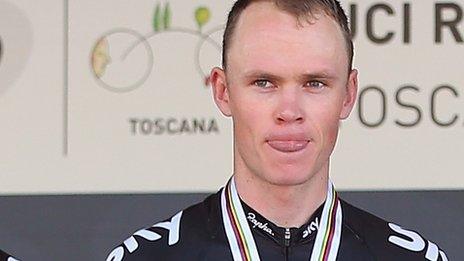

Cruel though it may appear, Wiggins is Team Sky's bright past. Chris Froome is its present and future.

Wiggins and Froome - team-mates and Britain's first two Tour de France winners

Froome, dominant winner of the yellow jersey in Wiggins's absence a year ago, has the ability, form and team to win again, not only this year but for several to come.

In Richie Porte he has a proven lieutenant, even if the Australian endured a difficult start to the year. In Wiggins he has a man who may have pledged to ride for him but could also have been a rival.

Teams have gone into Tours with two leading men before, most famously when Bernard Hinault and Greg LeMond duelled within the La Vie Claire team of 1986, but also when Sky attempted to meld Wiggins's slog for yellow with Mark Cavendish's sprint for green in 2012.

Team Sky's principal Sir Dave Brailsford, for all his long and lucrative relationship with Wiggins, has been unequivocal on his strategy. Only one rider can be propelled towards the summit. Bets cannot be hedged. Understudies, no matter decorated, cannot be accommodated.

"As far as my experience has been, if you want to win the biggest events in the world, normally the guy with plan A tends to win," he said recently. "It's not often you get, 'Let's revert to plan B' and you win. It's not the norm."

No-one should be surprised by the ruthlessness of Brailsford. No matter that he was trackside when Wiggins won individual pursuit gold in Athens or added the team pursuit crown in Beijing four years later, or there, both bemused and delighted, on the Champs-Elysees on Sunday, 22 July 2012.

As he demonstrated by selecting Jason Kenny ahead of national hero Chris Hoy for the single match sprint spot at London 2012, or in allowing Cavendish, the third in the triumvirate of British cycling gods, to leave Sky a few months further on, performance is all. So far, he has also been consistently vindicated.

That logic will do little to dampen our fascination in the relationship between Britain's two Tour winners, and how their rivalry has informed this latest plot line.

Some have likened Wiggins-Froome to Prost and Senna on two wheels, nominal team-mates with utterly contrasting characters and a barely disguised animosity.

But the two McLaren drivers went head to head at every race. Wiggins and Froome have been more like middle-distance runners Steve Ovett and Sebastian Coe, antagonistic adversaries who have actually raced each other only rarely.

Sky tactics and differing schedules have kept them apart so far this year. Wiggins's injuries prevented this current contretemps developing at last year's Tour.

For all Brailsford's detached decision-making, it is the steel at the core of the outwardly affable Froome which has been so striking in Wiggins's slow abdication from the throne.

Wiggins won the time trial on the road at London 2012

Whether through carefully chosen comment to journalists or extracts from his new autobiography, he has made it quite clear, in his cool reserved way, that he doesn't get on with Wiggins, and that others can do a better job for him.

"Chris is the most stubborn person I know," Froome's partner Michelle Cound told me last year. "He's just so focused on what he wants, and he'll do anything to get there."

That shouldn't be taken to mean that the 29-year-old is a Machiavellian schemer to rival Prost's depiction in the documentary Senna. To get to Paris in yellow from the cycling backwater of Kenya has taken remarkable perseverance. The words spoken and written since his own coronation last July have simply been the manifestation of that same determination: I know what I want, this is how I can get there.

Would Wiggins have buried himself for Froome, had he made the team? He would certainly protest so. Others would look at the resentment that has simmered between the two ever since the final kilometres of Stage 11 two years ago and wonder if three weeks sharing the same tarmac and team coach would not have weakened his resolve even fractionally.

On that mountain-top finish, Froome rode away from team leader Wiggins before being called back, visibly riled. A day later their partners argued about it on Twitter; 14 months further down the line, Wiggins was yet to pay Froome the Tour bonus that he had given, as protocol dictates, to the rest of his team-mates.

Olympic cycling: Watch Bradley Wiggins win time trial gold

Only a week ago, Froome described his old team leader as "mentally weak". These are deep and numerous wounds to leave no scar tissue.

Wiggins's own future now appears defined: a renewed tilt at the time trial and track in July's Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, a move on from the team he helped establish at the season's end.

How it will play out on the verges and pavements of Yorkshire, Cambridgeshire and London earlier in the month is less certain.

Froome has not yet been taken to heart by the public in the same way as Wiggins, his own remarkable backstory lost behind the older man's sideburns, collections of Gibson guitars and Lambretta scooters and penchant for a winning line.

Froome will never take the microphone at the moment of his greatest triumph to announce, "We're just going to draw the raffle numbers," as Wiggins did in Paris in 2012, or begin an interview on Sports Personality by referring to its host as "Susan" Barker.

For some he will always be Buzz Aldrin to Wiggins's Neil Armstrong. People care about the first man on the moon. If Froome takes giant leaps for many years to come, he is unlikely to ever match Wiggins's wider fame.

That will concern him far less than the climbs and sprints that will lie ahead for three weeks in July. Today he is in the perfect position to defend his Tour de France title. And, to a man with his laudable drive and ambition, that is all that matters.

- Published6 June 2014

- Published19 November 2013

- Published5 June 2014

- Published3 June 2014