Mark Cavendish on sprinting: 'It's not like playing chess'

- Published

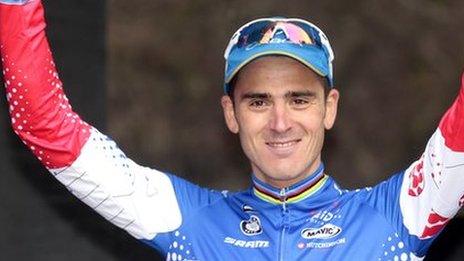

Mark Cavendish sprints to victory on stage three of the Tour of Qatar in 2013

Mark Cavendish: The Secret World of Sprinting |

|---|

He is the Usain Bolt of bike racing - winner of 25 stages at the Tour de France and 15 at the Giro D'Italia, a world champion on road and track, a Manx Missile capable of speeds that wreck rivals and destroy records.

No-one understands the pell-mell mayhem of a bunch sprint like Mark Cavendish. No-one before has taken the uninitiated inside that maelstrom quite like this. This is the secret world of sprinting, and it's quite some ride.

Calm before the storm: 'It's not like chess'

You think this is all about a big kick in the last 500 metres of a 120-mile stage? The night before, Etixx - Quick-Step's Cavendish will study Google Street View so he knows every corner and bollard from 2km out. But the lead-out begins, in the words of his long-time team-mate Mark Renshaw, as soon as you decide it's going to be a sprint stage.

"In a race weeks before, I'll make it look like I'm suffering, so a rival team will try to use their resources to drop me before a sprint," says Cavendish. "If they use their resources up, that's easier for me."

Neither is it a carefree tow in the peloton until the critical kilometres.

Cavendish says a team effort is crucial to setting up the perfect sprint finish

"Sometimes the hardest part of the stage is right at the beginning. The other teams will leave it to us to chase down a breakaway, and we can't allow a big group to go up the road - anything more than four riders is trouble.

"But it's not like playing chess. We're not robots. You have to have the physical strength to react to things.

"Between 20km and 10km to go, you want the whole team at the front. You don't necessarily want to take control, and the speed will be dictated by how many surges you get from the other teams. You don't want to go so fast they can't come, but you want to be just ahead so you're in control.

"The stronger you are as a unit, the more you can control a race. The strongest cyclist in the world isn't as strong as two guys, let alone nine."

10 km to go: 'It's getting harder than ever'

Seldom has the pace dropped below 30mph. It is hot, midsummer in the south of France. You are tired, thirsty and being bumped on all sides. And the brutal stuff is yet to start.

"I've already had my last food, a caffeine gel with 30 or 40km to go," Cavendish says. "I don't take anything after 20, because I don't want to take my hands off the bars, or reach round to my back packet. If you're grabbing your brakes with one hand in those conditions, it's not going to end well.

"Ideally you don't want to catch a breakaway too early. It leaves the race open to counter-attacks and chances for small breaks to form that you can't control, because they've been sheltering in the wheels all day.

Mark Cavendish MBE - vital statistics |

|---|

Age: 29 |

Place of birth: Douglas, Isle of Man |

Team: Etixx - Quick-Step |

Sprint speed: 48.47mph (78kph) |

Tour de France stage wins: - 25 (2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013) - third in all-time rankings |

Other notable achievements: 2013 National Road Race Champion, 2011 World Road Race Champion, 2011 BBC Sports Personality of the Year |

"Within the last 10km is perfect. There will be odd riders who attack in that, but you'll never get a full breakaway forming unless it's a difficult last 10km, in which case it probably won't be a sprint anyway.

"As racing has changed over the last few years it is getting harder than ever. It used to be that one team controlled it and other teams were fighting behind for that sprinter's wheel. Nowadays you've probably got five or six sprint teams, all vying for control of the peloton.

"The road might only be six or seven riders wide. So whereas before I had eight guys ahead of me, all controlling it with me in ninth, now you've got six teams on the front row. That doesn't just make you seventh; you've got six lots of nine which is 54 riders ahead or around you."

'An algorithm for every scenario'

This is both your job and your greatest skill, the few minutes of the greatest stress you can experience. How to control the adrenaline, hold your nerve with wheels an inch in front of yours and an inch behind, keep a grip on the endless calculations?

"Circumstances change in every moment of every race. The weather, the terrain, the other riders - it's not just me against another rider, it's my team against 20 other teams. So it's 20 things to the power of 20 that can happen. There are infinite things that can happen.

"But although it sounds quite unromantic, I don't actually get nervous. I get quite the opposite - I get quite clear-headed. I know what I have to do. It's like a procedure.

What's a watt? |

|---|

Sprinters' power output is measured in watts, most often associated with light bulbs |

Taking a maximum output of 1600W, a cyclist could produce enough power to illuminate 107 energy-saving light bulbs at 15W each |

The average UK home uses 34 light bulbs, meaning at 1600W, a cyclist could provide light for three UK homes |

"We talk about sprinters being aggressive riders, with all the bumping and barging. That's what it's like for most of the guys, but they rely on raw power.

"I'm not so powerful. I rely on - and always had to - on my road craft and instinct. So it's ingrained in me. I know what I have to do.

"There's a certain procedure, a certain algorithm inside me for every scenario. Going through a set of patterns to get the best possible result. Sometimes it doesn't work, because although you get the tactics right you physically can't do what you need. But most of the time, it happens."

3km to go: Swearing in European languages

The peloton has gone from band of brothers to angry swarm. Everyone is fighting for space, everyone is fighting for a wheel. Forget any notions of solidarity. This is elbows-out war.

"In the Olympic road race, the crowd was so loud that we couldn't hear each other. You couldn't even hear the man in front. So we have a system where I call to my lead-out man Renshaw, he calls to the rider in front and so on.

"It's not even a code. We have five words we say in our team. Left. Right. Go. Stop. Easy.

"Each word has to be clear and impossible to confuse as you pass it up the chain. It has to be 'stop' and not 'whoah', because 'whoah' could be confused with 'go'.

Cavendish sprints to World title

"With any other lead-out man I'd probably have to shout more things. With Mark (Renshaw), the only thing I have to say is his name. Because he knows he will never be so close to the pavement that I can't get on his wheel.

"He always thinks for me. If we're trying to move up the outside and I get cut off by another team, I'll shout 'Mark!' And he knows that's lost his wheel. It's the only thing it can mean."

Can Cavendish, not renowned for stepping back from confrontation, swear in four major European languages?

"I just say one word, and even in English it's not the best word to hear.

"The mentality you have to have is that you're the only one with the right to be there. And that's not just me. Every sprinter believes they are the only one who should be there, so how dare they fight you for it?"

Speeding up to slow down

"Speed?" remarked Jackie Stewart, a few months after winning the first of his three Formula 1 world titles in 1969. "The whole business is the reverse of speed. Speed doesn't exist for me unless I'm driving poorly. Then things seem to be coming at me quickly instead of passing in slow motion.

"In form, I see things a long way off, in fine detail. A corner will come towards me very slowly… everything is clear, neither hurried nor distorted, like a slowed-down movie film."

Sir Jackie Stewart sits in his Matra car before the race at Silverstone in 1969

As true for a road sprinter as a Grand Prix driver?

"That's a brilliant quote," says Cavendish. "That really is how it works.

"You know what's going on around you, you're aware of some things, but there's no detail in your peripheral vision. It's only what's in front of you.

"I watched a documentary on time recently, about how time is just what you perceive it to be. If your adrenaline is going, it's your body trying to absorb every bit of information, physical and emotional, so it can learn for the next time it happens to you.

"And that's what happens to me. It's what your body does in its instinctive state."

2km to go: 'That's when most people crack'

Let's imagine, by some horrible twist in the fabric of time, an ordinary club cyclist were to suddenly find themselves in the middle of that constantly shifting fight. How frightening would it be, how fast? Could they even stay upright?

"If you dropped a club cyclist into a neutral zone of a Tour stage, they would crash," says Cavendish. "Even most professional bike riders don't want to be near the front of a bunch sprint.

"The worst ones are the ones who believe they are fast when they're not. The thing about sprinting is that it's not being able to put out 1600 watts, it's being able to put out 1600 watts when you're in the red zone, when your body's at its limits. That's when most people crack.

"Sprinting on the velodrome is just going full gas. It's tactical, it's physical, but it's about pure sprinting. Endurance sprinting on the road is about being at your limit and then picking it up. Most guys can't do that. They think they can, but they're wrong.

"And they become bollards in the road. They're coming back so fast through the peloton that that's what happens.

"It's as if you get a dog, make him angry and then drop him in with three km to go. That's the scariest thing. It's not your rivals. It's the guys who physically aren't able to do it but think they are. They're the biggest hazard in the last few kilometres."

Man down: 'A massive breach of etiquette'

Which rider are you happy to see appearing alongside you? Whose number do you dread if it suddenly veers into your vision?

"There's a few. One of them is my rival Marcel Kittel's lead-out man, Tom Veelers.

"I had a collision with him in the Tour de France a few years ago. He sat up and started going backwards.

"If you're going backwards you get out of the road. You get out of the side.

"He comes back through the middle of the peloton. Then he starts looking over his shoulder.

"Deviating from your line is banned in the rules. Now, you're always going to deviate from your line unless you paint lanes on the road. But looking over your shoulder, not being on your drops? That's a massive breach of etiquette. It will cause a crash. You won't be lucky if it doesn't cause a crash, it just will."

Cavendish after a crash at the end of the fourth stage of the 2012 Tour de France

Are crashes, to borrow from the opening credits of Porridge, an occupational hazard - even the sort of crashes that leave you in the gutter of your mother's home town with a separated shoulder?

"It's part of the job. That's it. You can't think about consequences, because that's an emotion. And if there's an emotion there then you're not concentrating on the job in hand, which is winning.

"Everything is happening in slow motion. You have time to register that something's going to happen. A lot of the time it's not the exact moment you come off balance that you crash. You have a moment or two for you to realise."

Is there time to be angry before forearm even meets tarmac?

"Yeah. You say two letters. Which are F and U. Then you hit the deck. You don't have time to complete the words."

The relationship: 'It's a special, special thing'

Cavendish comes as a package. The other half is the Australian Renshaw, his lead-out man at both HTC and Quick Step, as essential to his sprint successes as the bike between his legs

"Me and Mark always room together. We are like the anti-each other. I'm quite angsty, always moving, always on edge. Mark is always calm, relaxed, almost boring.

"His personality transfers itself onto the bike. We could say the same thing, but it comes across so different. He'll just say it, but I'll scream it.

"There are very few people - two, three in my career - whose judgement I would take over my own in terms of positioning and movement in the peloton. Mark is definitely one of them. He's on the highest rank.

"He's the most gifted person I've ever seen at moving round the peloton, at knowing where to go. I don't even have to think if I trust him.

Mark Renshaw was also on the HTC Highroad team, a squad which helped Cavendish notch up 21 of his 25 Tour de France stage wins during 2008-2011

"If you have a lead-out man where you have to wonder what he's doing, it takes precious energy away from the sprint. With Mark it's as simple as just following him. He'll get it bang on where he has to be.

"He rides so smooth. He rides like he's riding a tandem, so if he goes through a space there has to be space for me to get through as well. If we move in the wind he stays a little bit out so I'm sheltered as well.

"He's always thinking for two people, which is a gift. You can't imagine saying to many sports people that that their role is entirely for someone else. It's a special, special thing, but we have a very good relationship. If he does it right, I'm going to finish it off."

The drop-off: 'You go deeper than most people could even imagine'

Faces in the crowd flashing by, your team-mates bailing one by one. Riding in Renshaw's slipstream, a rocket waiting for the final fuel tank to drop away.

"The perfect place to go really depends on the conditions. If you're talking an idealised stage, if everything has gone smoothly in a lead-out, if there's no corners, no wind, zero incline, same gradient… 230 metres, probably.

"It's about a 12-second effort that you want. If it's slightly downhill you'll go slightly earlier, if there's a slight headwind you'll go slightly later."

Head low over the bars, covering each metre in less than 0.05 of a second, how can you always sense where that point is?

"Sometimes tactically you have to go earlier or later. I always trained my sprint over-distance so that I can go earlier if need be. A lot of guys would die, but I've always trained for it.

"It's incredible the muscle damage you do in a sprint. You don't see it after the line, because we're smiling. But if you see the tent that we're in straight afterwards, you just collapse.

"You go deeper than most people could even imagine their body going. So if you can leave it late, you do - but you run the risk of someone coming round you, of boxing you in, and then you don't win anyway."

The jump: 'I went with such speed…'

This is it. Renshaw dies. 200 metres of empty road lie between you and victory. What is left in those pumping legs?

"The moment you accelerate is the moment you know if you've won the race," says Cavendish. "It's not how much power you can put out, but how quickly you can accelerate.

"Some days you can feel brilliant, then you go, and… nothing. In Milan - San Remo 2014, I had to go a little earlier because of the position I was in. When I went, I felt great the second before I kicked. I felt a surge.

"Then the second I went, you don't have time to analyse it, but you know it's not there. Three seconds later I had to sit down.

"It wasn't even through my legs being tired; it was that my legs stopped working. I had to sit down. Yet two seconds before I'd felt brilliant.

Mark Cavendish says he probably will not be able to compete in the Rio Olympics, as Matt Slater reports

"Sometimes I will spend the whole day on my hands and knees. On the last stage of the Tour of California, I spent the whole day thinking I was going to be dropped.

"I hadn't slept well, I was in pieces. Even on the last lap, following Mark, I was thinking, hmm.

"We started the last km, slightly downhill, and I'd put a bigger chain ring on the front to get a bigger gear, because it would be slightly faster downhill. Normally from the last kilometre you put it in your biggest gear. But I did, and I had to put it back down a gear, because my legs wouldn't do it.

"So I sat behind another guy, and with 200m to go it just felt like we were going a bit slow. Nobody was passing. I looked, and we were still in one line. So I thought, I'll try to sprint. And when I went, I went with such speed that I knew in that moment I would win by two or three bike lengths."

At your limits: 'Your legs can't turn any faster'

Where in the body do you die first - in screaming lungs, in maxed-out heart, in lactic-drenched legs?

"Now, with the aerodynamic advantages in the clothing, in the bikes we use, what limits us is the amount of pedal revolutions we can do.

"Imagine you smash your car into the rev limit - BABABABA! That's the sensation you get.

"It's such a speed that you physically can't turn your legs that quick. It's not that they're filling up with lactic acid. They just can't turn any faster.

"Most guys do between 120 and 130 rpm. And that's where I'm different. I don't put out anywhere near the same amount of power that the other sprinters do.

"I'm doing 1400, 1500 watts, they're doing 1800, 1900 watts, which is a good 20% more. But I can pedal that much quicker. I can pedal with an extra 10% cadence. And that's the difference."

It's one of those counter-intuitive truths in 100m sprinting in athletics: the man who crosses the line first is not the one going the fastest but the one who is slowing down the least.

"It's exactly the same for us. Peak power really isn't a good measure. You might be able to do 1800 watts, bang, but if you drop to 1000 it won't matter.

"I can hold within 20% of my max power for 12 seconds. Mark Renshaw has an even lower peak power, but he can hold that 30 seconds to a minute, which is a different thing all together.

"I wouldn't be able to sprint well at the velodrome. I don't put that amount of peak power out for that short a period of time. But when I'm in the red zone, I can put a high power out."

The moment of truth: Sweet victory, cruel defeat

A wheel alongside, a shoulder in your peripheral vision and a brightly coloured helmet beyond that. A dip and a desperate push of the bike forward. Who has got it?

"When you cross the finish line, you either see ecstasy on someone's face, or absolute horror," says Cavendish.

"It's like the world is coming to an end, because all the emotion that's been put to the back for the last two hours comes out. And it will come out in a massive fireball.

"For some riders it's a massive bonus them winning. They will be high on it. For me, it's my job to win.

"It's everybody's job to try to win, but I'm paid significantly more than a lot of people, and I have a team that's dedicated to the task.

"It's my job to win. It's bigger news, and has bigger consequences, if I don't win. I'll be more caught up in it if I don't win. Then it'll be a sleepless night.

Cavendish won BBC Sports Personality of the Year in 2011

"I've become quite reasonable as I've got older. If it's out of my control - a puncture, or I was in the right position but a dog ran in the road, you might be banged up or disappointed but you quickly forget it. But if I'm in the wrong position, if I make a mistake, that's bad.

"It's such a weird thing. In a sport where there are eight on the start line, second's still something. In cycling, you might have 200 bikes on the start line, but second doesn't mean a thing.

"You might be second, but you might as well be last. That's what makes it so special."

- Published22 June 2015

- Published22 June 2015

- Published22 June 2015

- Published11 January 2015

- Published4 September 2014

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013