'Doped bikes': Is this cycling's next cheating scandal?

- Published

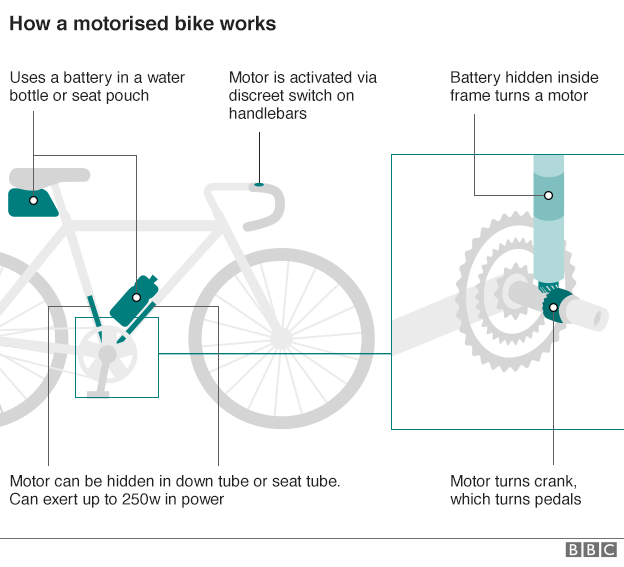

Doped bikes: An example of how it works

First it was doping, now it's tiny motors hidden inside the frame that could threaten cycling's credibility...

The first top-level case of "technological fraud" came to light after a bike was seized at the Cyclo-cross World Championships on Saturday.

Belgium's Femke Van den Driessche, who was riding it, said she knew nothing about the device and that the bike belonged to someone else.

But the International Cycling Union (UCI) is investigating and the bike manufacturer is threatening legal action against Van den Driessche.

Why is it such a big deal?

Cycling has a long and chequered history of cheating, with those seeking to gain an illegal advantage traditionally using drugs.

There are numerous examples of blood dopers, with the most notorious being Lance Armstrong.

The American was stripped of his seven Tour de France titles after being accused of the "most sophisticated, professionalised and successful doping programme that sport has ever seen".

Now, just when it looked like cycling was cleaning up its act, a new threat has emerged: doped cycles.

How much of a problem is it?

Nothing has been proven yet but there have been plenty of rumours, not to mention allegations, against some of the world's top riders.

Swiss rider Fabian Cancellara was accused, external of "mechanical doping" in 2010 after an Italian film released on YouTube claimed to show how the Olympic time trial champion used a battery-powered motor.

In 2014, the UCI investigated allegations that Canada's Ryder Hesjedal used a motorised bike after video footage, external seemed to show the rider's wheel moving by itself following a crash at the Vuelta a Espana.

Cancellara and Hesjedal denied the allegations, calling them "stupid" or "ridiculous".

Former Tour de France champion Alberto Contador has also been forced to deny allegations of using a motor-powered bike., external

How do 'doped bikes' work?

Motorised bikes are available to the public and designed to encourage people to take up cycling, although it costs thousands of pounds to buy a basic model.

Riders still have to pedal them, but they can also get assistance from a battery-powered engine.

"It isn't a scooter, you need to work hard yourself," says Harry Gibbings, chief executive of Typhoon, a company that builds these kind of bikes.

"You have to cycle and then you push a button. The silent motor is engaged and, to the person on the bike, it feels like someone is giving them a push."

The motor can produce up to 250 watts of power and gives motorised assistance up to a speed of 25km an hour.

Is that a big deal?

Existing technology on some commercially available motorised bicycles has a larger battery stored in the water bottle, rather than a smaller battery hidden in the frame

Former Olympic cyclist Rob Hayles believes the advantage of using a motorised bike is huge, especially during hill climbs.

"If you are averaging say 350 watts for a 200km race and if you can generate an extra 50 watts, then that is a big percentage," he says.

"It would be the equivalent of attacking off the front and going solo but feeling like you are on the wheel, slip-streaming.

"To get that advantage without actually being behind anyone is enormous. It is a bigger advantage than doping. With doping, your body still has to do the work."

How are motors detected?

An electric motor was said to have been found in the frame of Femke van den Driessche's bike

A report in cyclo-cross magazine Grit.cx, external said UCI officials were seen using a tablet-like device to check for mechanisms inside the frame of Van den Driessche's bike.

Apparently, the device used electromagnetic-based technology to help detect the secret motor.

Once officials decided closer inspection was needed, they removed the seat post to find wires poking out.

The UCI says it has been taking the issue of technological fraud "extremely seriously" for many years, adding it had recently been trialling new methods of detection.

It also says it is using industry "intelligence" and random testing to try to catch cheats, revealing it carried out 100 tests at the Cyclo-cross World Championships.

Two-time Tour de France winner Chris Froome has urged the UCI to start checking bikes more regularly after hearing "rumours" of hidden motors.

Is it worse than doping?

"Maybe," says Hayles, a cycling commentator for BBC Radio 5 live. "Cheating is cheating. But if doping is already over stepping the mark, then this is like kicking the door in.

"People are always looking for advantage - look at the lengths that people went to with doping - but this is more of an advantage than any drugs could give you."

BBC cycling reporter Matt Slater adds: "While the degrees of cheating might change, the essential act of trying to get one over on your rivals has not,.

"That much is hard-wired into the part of the cyclist that has not changed at all in a century: the brain.

"So some cyclists are cheats, just as some accountants, bankers and cooks are cheats. The human being is a flawed machine."

An close-up image of a motor hidden inside the frame - picture provided by Steve Punchard

- Published2 February 2016

- Published31 January 2016

- Published4 September 2014

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2016