Sir Bradley Wiggins & the DCMS report: Yellow jerseys, gold medals and shades of grey

- Published

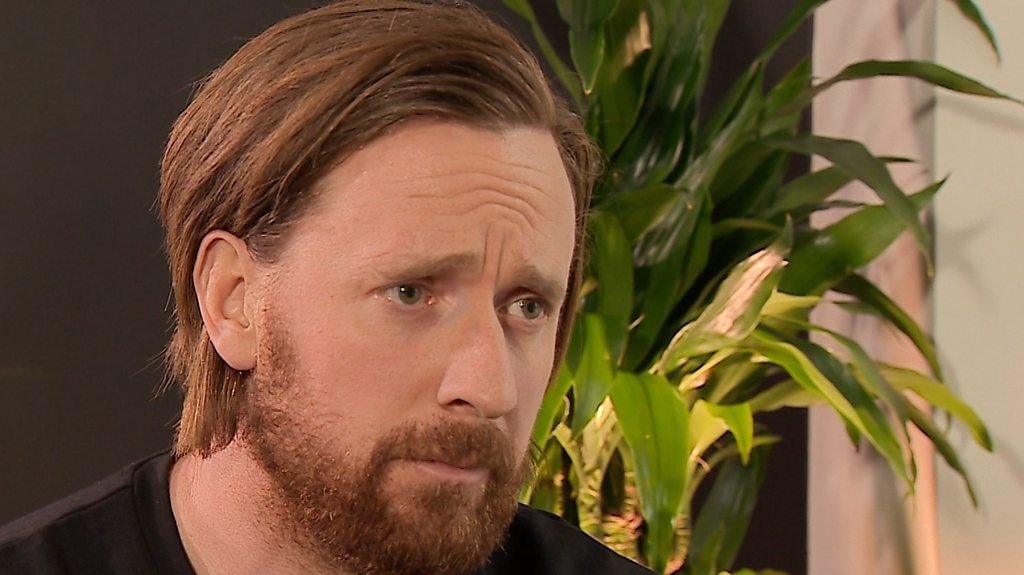

We did not cross the ethical line - Wiggins

On the wall of my kitchen, alongside various other souvenirs of sporting events and musical memorabilia, is a framed print of Sir Bradley Wiggins' smiling face.

It is a graphic artist's reimagining, the cyclist's eyebrows forming the handlebars of a bike, his nose the front forks, his grin the curved road under the wheel.

It has been there since 2012, and it is there as a representation of everything that happened in that wonderful sporting year - the London Olympics, that record medal haul, the sense of national giddiness and joy that came with it all.

Wiggins embodied it like no-one else: celebrating his Tour de France victory on the Champs-Elysees by talking about drawing the raffle tickets, walking out at the Olympic opening ceremony in yellow to bring the place down, lounging in a throne at Hampton Court Palace after winning time-trial gold. British to the core yet different to anything seen before, the definition of an undemonstrative nation's new swagger and confidence.

And then some of that golden glow began to fade, and darker shades begin to leak in. For the past 18 months, as allegations and revelations have piled up, one friend has marked each visit by pointing at the print and raising his eyebrows. "Still got that poster up?"

I looked at it again on Monday morning, as the implications of the Digital Culture, Media and Sport committee's report into doping in British sport began to spread, as the Sun newspaper, which had marked Wiggins' Tour de France triumph with cut-out-and-keep stick-on sideburns, screamed "WIGGO DOPING SHOCK" in maximum point size on its front page.

Belief takes a while to build and it never fades quickly. Nuance gets lost in big headlines and confusion soon follows.

A knock on the door, a visit from my 83-year-old neighbour. "What's this about Wiggins being a dope cheat? Does this involve all the Brits?"

You try to turn the grey areas black and white, to make clear the murky rules that were in place around therapeutic use exemptions (TUEs) and explain the difference between legal medicines used unethically and banned medicines used illegally. You say, no, this does not involve every British cyclist, and that there are thousands of clean athletes out there.

The neighbour wants a certainty you can't provide. Is Wiggins a good man or a bad guy? You try to tell him that athletes can be both. Good people do bad things.

He shakes his head. Not in his world they don't.

The poster hanging in Tom Fordyce's kitchen - "Still got that poster up?"

Back to the kitchen, the poster looking down at you. A line from the DCMS report highlighted on your laptop: "We believe that this powerful corticosteroid [triamcinolone] was being used to prepare Bradley Wiggins, and possibly other riders supporting him, for the Tour de France.

"The purpose of this was not to treat medical need, but to improve his power-to-weight ratio ahead of the race."

A text from a mate who only follows cycling around the Tour and Olympics. "It's dodgy. You don't inject a powerful steroid for performance-enhancing means but find a loophole saying it's for medical grounds."

You think back to January 2010, and standing outside Buckingham Palace as the newly formed Team Sky rode down the Mall and past St James's Park. Optimism in the cold winter air, Wiggins leading the pace-line, Dave Brailsford round the corner at Millbank Tower telling all assembled that there would be a British winner of the Tour within five years.

Brailsford, the man behind Great Britain's eight Olympic golds in Beijing two years before, ambition mixing with £35m of hard cash to create what seemed like certainty. "We like to think that we're at the forefront of trying to promote clean cycling," he said. "That philosophy will always stay. If we thought it wasn't possible then I'd be out."

You think back to all that excitement and solid belief. And you jump back to the DCMS report.

"Team Sky's statements that coaches and team managers are largely unaware of the methods used by the medical staff to prepare pro cyclists for major races seem incredible and inconsistent with their original aim of 'winning clean'… David Brailsford must take responsibility for these failures."

Brailsford, speaking in 2017 to the BBC about Team Sky

A WhatsApp message arrives from a friend who loves to cycle and loves to read cycling books.

"Not sure if I'm all that happy with MPs standing in moral judgement on this. Playing with boundaries of rules and fairness a given for me in elite sport. But that would mean I'm condoning drug-taking. I'm flummoxed by it all if I'm honest."

When you have believed and celebrated, when you have shared the triumphs and felt them strong on your back when you ride out on your own adventures, you don't want to stop.

Wiggins on the Champs-Elysees, Wiggins on the throne, Wiggins at Sports Personality of the Year calling Sue Barker "Susan" and winning from Jessica Ennis-Hill and Andy Murray with almost half a million votes, climbing up on stage at the after-show party to interrupt the band, grab a guitar and lead the crowd in a spontaneous version of That's Entertainment.

I think back to the Vuelta a Espana in September last year, and Spain's great cycling hero Alberto Contador ending his career on Madrid's Prado, not a mention in the national media nor doubt on the local fans' faces about his chequered past, of being stripped of the 2010 Tour and 2011 Giro, of the tendrils tying him to the Operacion Puerto doping scandal.

You choose your heroes but you don't control them. You fly along in their slipstream but when they go down you go down with them.

Another line from the DCMS report. "This does not constitute a violation of the World Anti-Doping Agency code, but it does cross the ethical line that David Brailsford says he himself drew for Team Sky. We believe that drugs were being used by Team Sky, within the Wada rules, to enhance the performance of riders, and not just to treat medical need."

Within the rules but outside an ethical code. Grey areas around a yellow jersey, doubt and hope and past disappointments mixing together, memories of dark days thought done coming back to the surface.

You look up a dictionary definition. "CHEAT: To act dishonestly or unfairly in order to gain an advantage."

And then you ask yourself why you should be looking up that word when you are dealing with sport, which is supposed to be the great distraction from all the serious stuff in the world, our refuge from the chicanery and darkness, a place to cheer and sing and know that none of it ultimately matters.

A tweet from an old colleague. "At some point, cycling fans will just have to concede that biking up the side of very steep mountains for weeks on end is utterly absurd, to the extent that people are always, always going to cheat at it."

You know clean riders. You know cyclists you trust, and people at British Cycling and Sky who have done great things for a sport that was on its knees.

You think back too to a couple of other athletes who you have known and trusted who turned out to be taking shortcuts, men you liked and spent social time with. Good people do bad things, and no-one wins when they do.

Wiggins does a television interview. A phone call from a colleague: he has watched it, and he sees an honest man telling the truth. A call from another colleague: he has been listening to it on the radio in his car, and denials, the wording, he says, makes him think of Lance Armstrong and all those interviews before the truth finally, reluctantly, came out.

A line from Wiggins that stays in your head.

"I can't control that, what people are going to think or not think. All I can tell you is from my point of view, what I experienced. Some people, whatever you're going to do is never going to be good enough. I just don't know any more in this sport."

And you look up at the poster on the wall again, and you wonder.

- Published5 March 2018

- Published5 March 2018