Cyclist Molly Weaver on the crash that led to depression and the unhealthy drive for perfection

- Published

Weaver raced the Giro Rosa in Italy less than six months after the crash

Molly Weaver broke her neck, five vertebrae, her sternum, a shoulder and four ribs, punctured a lung and tore a kidney when she was hit by a car.

The professional cyclist could have been killed, or at the very least paralysed. But within seven weeks, she was back on her bike, and told her mum she could "never be unhappy again".

Fifteen months on, those physical injuries have healed but the psychological consequences persist - and not the ones she predicted. The 24-year-old has stepped away from the sport after depression robbed her of her passion for cycling.

"I felt like I was in this euphoria. But that burns out eventually and reality hits you again," she says.

Now she tells BBC Sport about the pressure that "chipped away" at her on her return to cycling, the "fundamental problem" of perfectionism among athletes, and taking off the mask.

'It was such a joy to be alive' - the crash

Before 2017, I'd say my life was as simple as it could be in the world of professional sport. It wasn't all sunshine and roses, but I was still living my dream.

Weaver doesn't remember the crash from February last year. She couldn't even tell you the date. She was due to leave for a training camp the next day so decided to go for an "easy" ride near her home in Girona, Spain.

As she rode along a route she rides every day, a speeding car overshot a corner and hit her head-on. Had she not been in such excellent physical condition, it is very likely she would not have survived.

"Straightaway they told me that I had broken my back and neck," she says. "I just accepted that it had happened. I found that I wasn't really dwelling on it too much.

"I left hospital before they thought I would, I was walking before they thought - I was always overachieving. It was such a joy to be alive.

"It was only once I got back to riding, to being a cyclist again, that it flipped the other way and I became very aware of what I had lost."

Weaver was discharged from hospital a week after the crash but wore a back and neck brace for two months

'You feel you have to lie' - the aftermath

It's not that athletes want to be perfect, they just don't want to show weakness.

Following spells with Matrix Pro Cycling and Team Sunweb, Weaver joined Trek-Drops in January 2018 to become their road captain.

But by then the cracks has already started to show. She says she "didn't feel the same" and quickly realised she wasn't going to be the rider she once knew she could be. In May, she announced she was taking a hiatus from the sport to focus on her mental health.

"I was probably pressured into coming back quicker than I wanted to," she says. "It felt like that was what I needed to do.

"I think I was setting myself up for failure. Every setback chipped away at who I was, and it eventually caught up with me."

In sport, there seems to be an unspoken assumption that weaknesses must be hidden and not talked about.

It's a pressure that can take its toll on athletes, and ultimately undermine their performance. Yet only one of the professional teams Weaver has raced for has had a sports psychologist - something she says is a "fundamental problem with the industry".

"Externally, there is almost this narrative that you want to see played out, and that you know other people want to see play out. You want to be that person for them," Weaver says.

"But you can't necessarily be that person - life isn't perfect. You really feel that you have to lie your way through it, hide it and not let anyone see it.

"You feel like that would be showing weakness that others would prey on."

'It was tiring to keep up the act' - taking off the mask

You don't want others to know. You are ashamed of it, but you don't want the attention on it.

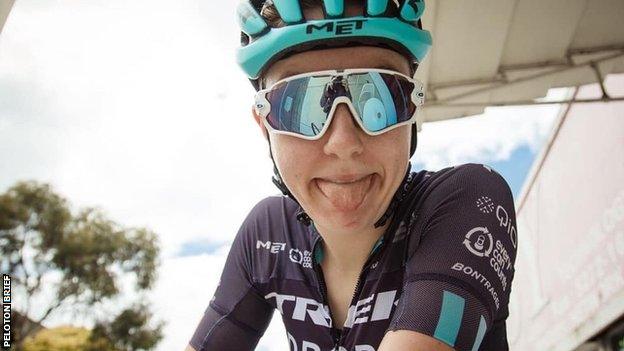

Flick through Weaver's Instagram, external page and you're presented with images of idyllic backdrops to training rides, selfies with animals and smiles. Lots of smiles.

How could this account belong to someone who has depression? Easy. Social media allows users to portray the picture they want others to see.

But those with mental health problems often describe hiding behind a mask, their true feelings obscured from public view - and Weaver was no different.

"In public, I'd be one person - I'd be very confident, outgoing and talkative, smiley and chatty. That is who I am so that's what I wanted to be like," she says.

"As soon as I'd get home, I was on my own, and it is really tiring to keep that act up all the time. It would hit me twice as hard.

"I didn't want to be labelled as someone who had suffered with mental health problems, I didn't want to be the rider who stepped away due to depression, but actually, how many people are there out there hiding this?

"It makes you wonder why people are lying, why they are presenting this picture. Obviously no-one wants to be depressive and down the whole time, but I also think there is a certain element of 'why can't we be more honest about how things really are?'"

"I'd be very confident, outgoing and talkative, smiley and chatty - that is who I am"

'You can rise again' - the future

I'm just going to see where life takes me and explore other things that I want to do. I just want to fall back in love with riding a bike.

Weaver had a promising cycling career ahead of her but, for now, that is on the backburner. Health and happiness are the priorities.

While ideas are in the pipeline, she's unsure what the future holds, but knows life on two wheels will never not be an option.

"I don't have any plan to return at the moment, but I also don't have any plan not to," she says. "I don't want to close the door on it and it be all over.

"Hopefully one day it will circle back around but if things go a different direction and I find something else, I'm not going to put pressure on myself to go back to cycling."

Just below her left elbow, Weaver has a tattoo that reads 'Still I Rise'. A fan of the ink, it was the first tattoo she got post-accident and serves as a permanent reminder of what she has - and continues to - overcome.

"You can rise again, it's not as though one thing happens to you - whether it's an accident, depression or anything - and that's the end of your story," she says. "You can become who you want to be."