Tour de France 2018: Why is there no women's equivalent?

- Published

- comments

Tour de France Feminin winner Marianne Martin shared the podium with Tour winner Laurent Fignon in 1984 - has cycling gone backwards since?

Why is there no women's Tour de France? Simply business or "blatant sexism", as former cyclist Kathryn Bertine claims? And will there be one any time soon?

On Tuesday, before the men's Tour resumes with stage 10, the world's top female riders will race in La Course.

It will only run as a single mountain stage this summer, having been a two-day event last year and held on the Champs-Elysees before the final stage of the men's race in its previous three outings since it began in 2014.

Bertine, who helped found campaign group Le Tour Entier to press the case for a women's Tour, describes that as "throwing women a token".

"It should be a five to 10-day race minimum by now," she told BBC Sport. "They probably don't even see it as sexism, but you could also say that it's just very lazy.

"The very top of the sport is where sexism is still strongest and that's what needs to be dismantled."

Tour organisers Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO) relented to Le Tour Entier's lobbying in 2014 by introducing La Course and Yann Le Moenner, the company's chief executive, said in March that the growing profile of women's cycling meant it "will definitely deserve a dedicated" equivalent of the Tour and "the sooner the better."

But what is the view from the world of women's cycling? What would a women's Tour look like? And will finance always be an issue?

'I need to push for change with my voice as well as my legs'

Former British cyclist Nicole Cooke, who won the 2004 Giro Rosa and the Grande Boucle in 2006 and 2007, told a parliamentary select committee last year that cycling is a sport "run by men, for men".

Do female riders still fear the consequences of speaking out?

Bertine is heartened by hearing more current professional riders speaking with "courage" but says being under contract with teams makes that difficult for many others, especially because of the current lack of a minimum wage in the sport.

Australian Tiffany Cromwell, who rides for Canyon SRAM, told BBC Sport it is "a fine line" between wanting to be positive to have opportunities and "needing to speak up" to ensure progress does not stall.

And Britain's former world champion Lizzie Deignan says a lot of women "may be put off speaking out about sexism" because of reactions they have had and "there is no doubt staying quiet is the easier option".

"I sometimes get frustrated that I am asked about politics rather than my performance," she told BBC Sport.

"But I am a passionate feminist and I understand people won't get to watch without me pushing for change with my voice as well as my legs."

Shorter stages & simultaneous schedules?

Rochelle Gilmore, a former professional and the founder and owner of the Wiggle High5 team, says a women's Tour should be "at least 10 days" and held on the same days and courses as the men's race - something Le Moenner said is "logistically, just not possible".

This year's La Course uses a similar route to stage 10 of the Tour but spans 112.5km compared to 159km, even though UCI rules permit one-day road races on the women's World Tour to run to 160km.

Currently, the women's Giro d'Italia - known as the Giro Rosa - consists of 10 stages compared to 21 in the men's version and coincides with the Tour de France. The 2018 edition was won by Annemiek van Vleuten on Sunday.

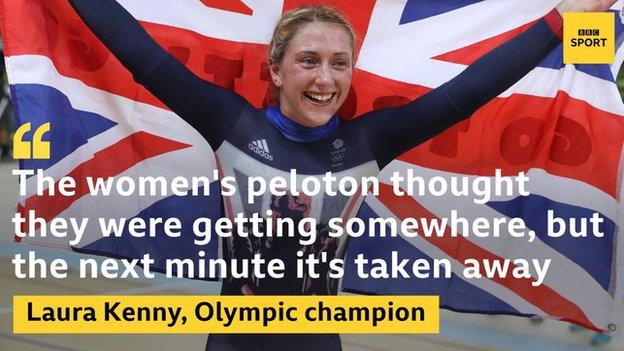

Cromwell believes a women's Tour needs to "play off" the men's race "to have the exposure", while Britain's four-time Olympic champion Laura Kenny, who won the national road race title in 2014, supports "shorter, more exciting" stages in both men's and women's Grand Tours.

Bertine, who rode the inaugural 2014 edition of La Course, says women are still fighting "the out-dated philosophy of the good old boys' network" who think female riders can only race shorter distances.

However, she does believe a French equivalent of the Giro Rosa is "technically not far off at all" and the only thing "standing in the way" is ASO's reluctance.

Kenny added: "It's frustrating, because when [La Course] was over two days, you felt like we were getting somewhere, but the next minute it's taken it away again."

Gilmore thinks it will happen in the next few years but Deignan, who finished second to Van Vleuten in La Course last year, does not envisage it happening any time soon.

"But I hope to see it in my lifetime," she said. "Society is changing quickly and I'm sure the next generation of female athletes will have more opportunities than I did."

Is it all down to money?

Finance is a major factor in whatever ASO decides because, unlike other international sporting events, the Tour is operated by a private company and not a governing body.

There was a women's Tour - the Tour de France Feminin - which ran alongside the men's race for five years from 1984.

But the 18-stage race dwindled over the years as a result of low investment, missing editions and a rebrand forced by a legal challenge from the previous organisers of the men's Tour. The final version was the 2009 Grande Boucle, which featured only four stages.

Gilmore said ASO do support and are interested in women's cycling, given they run women's one-day classics Fleche Wallonne and Liege-Bastogne-Liege and help promote the Tour de Yorkshire.

However, she points out that they are "taking into account when and where and how they can profit from it".

She added: "The raw truth is it's going to take an investment for a long period of time at possibly a loss to support it."

Accounts released in November, external show that ASO made 45.91m euros in profit in 2016, which Bertine points to as proof they could already afford to invest in a women's Tour.

She believes not adding a women's Tour to their portfolio is a "bad business decision" as it risks alienating half their potential audience.

Bertine added: "The revenue generated in terms of sponsorship, publicity agreements, media exposure and advertisements would absolutely come back to those who invest."

The BBC contacted ASO for comment but they are yet to respond.