Tour de France: 'Geraint Thomas has tamed a race in which he appeared cursed'

- Published

- comments

Geraint Thomas was racing in his ninth Tour de France

There was a time when Geraint Thomas appeared to be blessed with talent but cursed by the rider it made him.

A rider described by Sir Dave Brailsford as one who could do everything, a racer who seemed destined instead to ride for others, who kept crashing when openings came.

Down on the final descent of the Olympic road race in 2016, down twice at the Tour de France in 2017, down when in wonderful form at the Giro d'Italia the same year. Your chances in elite sport come fast and slip away faster.

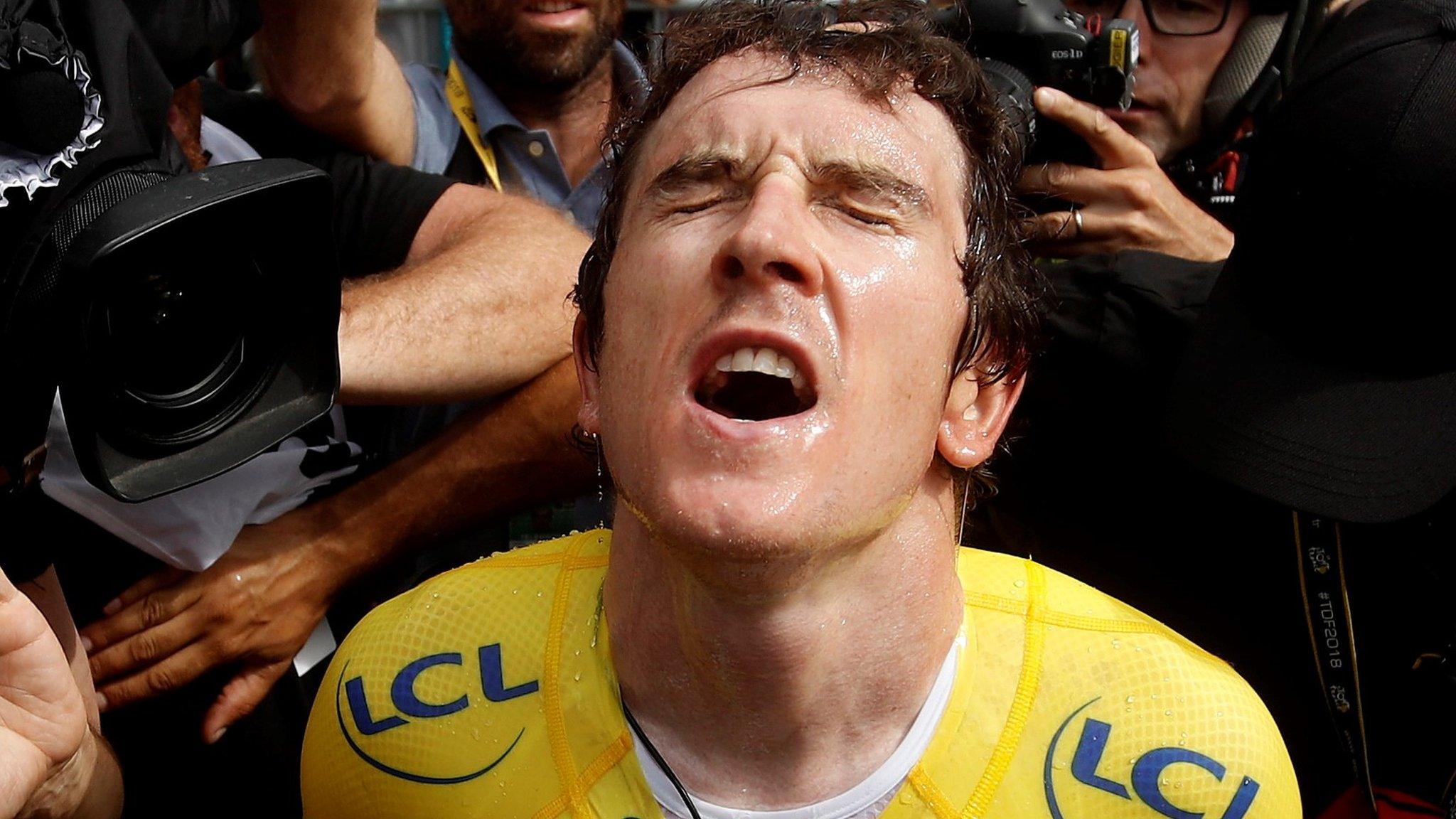

Now that curse is gone, blown away over the past three weeks in relentless and spectacular fashion. In its place, a certain giddiness, a happy disbelief, a triumph bigger than any of those disappointments combined.

Thomas watched his old Great Britain team-mate Bradley Wiggins win the 2012 Tour de France. He has helped Chris Froome to the podium in Paris three times, once having ridden for 20 days with a fractured pelvis. He has stood aside so Froome could chase other Grand Tours that Thomas might otherwise have won.

At 32, an age when riders start looking over their shoulder at younger, fresher talents, Thomas' reward has come.

And when he stood on the Champs-Elysees on Sunday evening, blinking at the hundreds of photographers and thousands of fellow Welshmen who had travelled to witness the coronation, his happiness was shared far beyond.

'It's just insane really' - Thomas reacts to Tour de France win

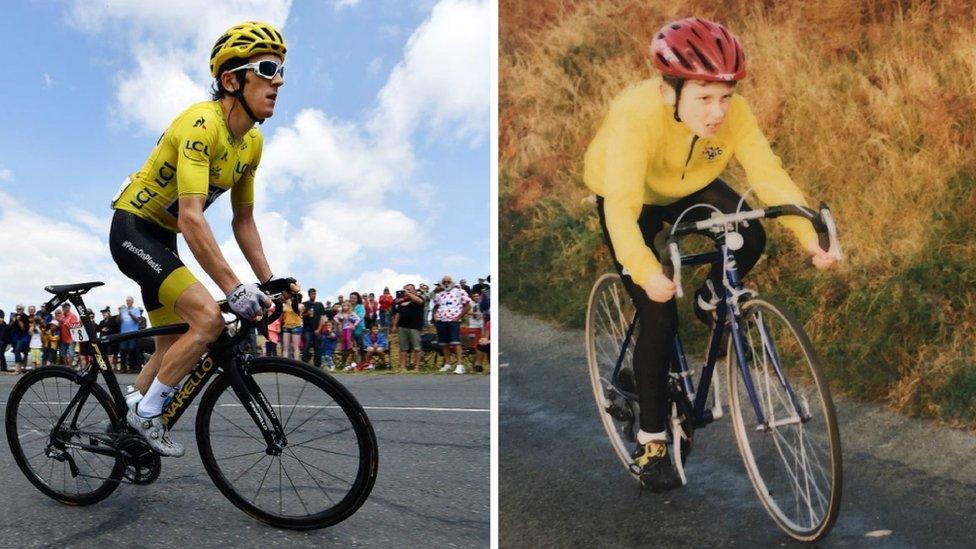

Some sporting heroes seem to have landed from another world. Thomas inhabits the same one as all of us. His first bike as a kid was a cheap mountain bike called The Wolf. On the handlebars he had a small box that made big noises - police sirens, ambulances, fire engines. He rode it to the park with his little brother and dad to play football and rugby.

When he was given his first pair of cycling shorts, he had no idea you weren't supposed to wear pants under them.

When he went out for his first long ride, from his home in the Cardiff suburbs to the Storey Arms outdoor centre in Brecon, he got lost on the way back and was so tired on his eventual return that he had to press the doorbell with his forehead.

When his mum realised this cycling thing wasn't going away, she used to fuel her son the night before rides with barbecue spare ribs and egg-fried rice from the local Chinese takeaway, and with jam sandwiches wrapped in foil for the adventure itself.

The rise of Thomas from the early days with Maindy Flyers

As the rides got longer and the successes began to come, winning Olympic gold in Beijing 2008 as part of the GB team pursuit quartet, the boy grew up but stayed the same.

He shared a house with Mark Cavendish and Ed Clancy near the National Cycling Centre in Manchester and was berated by Cavendish for not washing up to sufficiently exacting standards.

He rode the same roads as all the amateurs and weekenders in the north-west - the Cat and Fiddle climb out of Macclesfield, the Brickworks out of Pott Shrigley, Winnats Pass, Holme Moss.

The Tour de France was both real and impossible. When Thomas rode it for the first time, as a chunky 21-year-old in the colours of the struggling Barloworld team, he found the pace of it baffling. Sent back to the team car mid-stage to fetch water bottles for his team-mates, he could only get back to the peloton by lobbing all the bottles away.

Thomas was 140th out of 141 finishers on his Tour debut in 2007

On climbs he would be dropped instantly. On flat stages he would be dropped all the same. Sometimes his bike computer would auto-pause, assuming he had stopped because he was ascending the big mountains so slowly. All the time the same thought was rattling round his exhausted mind: how can you come to a race like this and actually try to win it? It's hard enough to finish a day...

The transformation came slowly but inexorably. From finishing the Tour to becoming Froome's key lieutenant. Losing the puppy fat, losing some of the muscle that gives track riders their power. Horrendous training reps up Mount Teide in Tenerife, taking in altitude and long drags and brutal climbs. Ditching the spring one-day Classics for summer's Grand Tours, finishing 15th at the Tour, learning from Wiggins and Froome and everything Team Sky's coaches and nutritionists could throw at him.

This July he has ridden with the experience of a veteran and the confidence of a man who knows his time at last has come.

There are those who would put it down to luck, to the punctures and crashes sustained by his rivals. Richie Porte out after a fall on the road to Roubaix, Vincenzo Nibali brought down by a spectator on Alpe d'Huez. Tom Dumoulin lost time to a flat tyre and then a penalty for drafting before the Mur de Bretagne. Froome crashed on the very first stage.

Had Dumoulin and Froome stayed safe throughout, they would still not be within 45 seconds of Thomas. On seven different stages in this Tour, Thomas has taken time out of Dumoulin, the man who will finish second. Dumoulin took time from Thomas only on the penultimate stage on Saturday, and even then only 14 seconds.

Has Thomas been lucky? Luck at the Tour comes with cleverness, with putting yourself in the right place in a constantly shifting mass of 100 or more riders racing at 45 miles per hour, of reading the body language and moves of those looking to attack you and ambush you, of eating right and holding the concentration not only on the climbs but on treacherous, slippery descents too.

Luck comes from reconnoitring mountains and throwing yourself into the brutal training sessions that can get you through them. Thomas had ridden the time trial course three times weeks before the Tour began.

Sky have once again been the dominant team at this race. They have won each of the past four Grand Tours, and six of the past seven Tours de France. In riders like Michal Kwiatowski and Egan Bernal, they have domestiques who would be outright leaders at other teams.

Geraint Thomas won two stages in this year's Tour de France

Thomas would not have won this race without Sky. Sky would not have won three other Tours without Thomas. You invest and you work and you accept the dividend that comes your way.

There are multiple subplots across the three weeks and 3,300km of a Tour. Some flare brightly before dying away like meteors across the night sky: the early sprint-stage wins of Fernando Gaviria and Dylan Groenewegen, the redemption of John Degenkolb on the cobbles of Roubaix.

Some light up the darkness for longer. Thomas' successes, first in the breathless summit finish on La Rosiere, then the unforgettable win up the iconic hairpins of Alpe d'Huez, have burned his name into the firmament.

The extraordinary could not have happened to a more down-to-earth man. The Tour has not always been blessed nor enhanced by its victors. There are asterisks where some winners once were and questions over others.

Thomas may never win another Grand Tour. But he will remain the inadvertent anti-Lance: always amiable, usually praising others first, never cocky, consistently self-deprecating.

He will probably struggle for some time to accept that he has finally won his sport's greatest prize.

The Tour in turn should feel grateful that the kid who started on Caerphilly Mountain, who first fell in love with cycling on the Rhigos - a climb that starts by a south Wales industrial estate and rises past an old colliery - who respects this race's traditions and who learned how to tame it, has now claimed its greatest prize as his own.

- Published28 July 2018

- Attribution

- Published23 July 2018

- Attribution

- Published28 July 2018