Team Sky: Why now and what now? The big questions facing cycling team

- Published

Froome, Brailsford and Thomas react to Sky's sponsorship withdrawal

Team Sky is facing an uncertain future after media company Sky announced it will withdraw its backing at the end of 2019.

Here are the big questions that arise from Sky's decision and the issues that the team now face.

Why now?

Well-placed Sky sources insist the decision - taken by chief executive Jeremy Darroch - was part of a natural review of commercial partnerships following the recent £30bn takeover of the satellite broadcaster by US media giant Comcast.

They deny that the departure of former Sky supremo James Murdoch following the deal - a man who was known to be especially passionate about the cycling team - was a factor.

And they insist it had nothing to do with the series of controversies that has so damaged the team's reputation in recent years.

It may indeed simply be that Sky feels the partnership will have run its course after 10 years, that it has achieved everything possible, and that there were other priorities.

Ten years ago, with the London 2012 Olympics on the horizon, the then newly appointed Darroch asked a team of his executives to search for a sport in which Sky could invest, and help increase participation. Swimming was briefly considered, but finally they settled on cycling, and partnered with the sport's national governing body to support its Olympic and Paralympic teams.

Following multiple medal success at Beijing 2008, the idea of a pro road-racing team was born. The rest is history.

But Sky has previously shown that such partnerships cannot be taken for granted. This is a hard-nosed business that constantly assesses the value of its investments.

In 2015 Sky announced its eight-year deal with British Cycling would end after Rio 2016. Its support of Team Sky was destined to last another three years, but I understand the company is now keen to invest in a major cricket participation project in conjunction with the England and Wales Cricket Board, alongside their support of environmental campaigns.

Supporting Team Sky has not been cheap - last year it cost the owners £25m to run - and with the company committed to spending £3.6bn over the next three years for Premier League football rights, some tough decisions had to be made. Maybe this was one of them.

What will the team's legacy be?

Chris Froome won Team Sky's first Giro d'Italia title earlier this year

Unprecedented elite cycling success, an upsurge in popularity for the sport, but also, as detailed below, considerable controversy.

Indeed, in the post-London 2012 era, it is hard to think of another British sporting institution that has thrown up so many big stories, both positive and negative, for journalists to cover.

Thanks to unmatched levels of financial support from their main backer, Team Sky have come to dominate their sport in recent years.

It is hard to overstate the extent to which British fortunes in professional cycling have been transformed. Until six years ago, no British rider had won any of the three Grand Tours. When the idea of a British winner of the Tour de France was first mooted by Sir Dave Brailsford in 2009,, external he was laughed at.

Now no-one is laughing. Sky have won all three of the Grand Tours, including six of the last seven editions of the Tour. Sir Bradley Wiggins' historic triumph in 2012 provided the perfect build-up to the London Games. Team Sky made household names of cyclists in a way British sport had never seen before.

Before events called it into question, the team's so-called 'marginal gains' philosophy became emblematic of a meticulous and scientific approach to sports performance and preparation that - alongside National Lottery funding - was credited with turning the country into an Olympic and Paralympic superpower.

That success bred a mixture of admiration, jealousy and suspicion abroad, and a surge in popularity and participation in the UK. There is no doubt that it helped Britain to become a cycling nation, and that this legacy should last whatever now happens to the team.

Next year Yorkshire will host the Road World Championships. Unprecedented numbers of fans flock to watch the Tour de Yorkshire and Tour of Britain each year. UK Sport has ambitions to host the starts of all three Grand Tours in the next few years. Sky also points to the success of initiatives like Sky Ride in getting 1.7 million people active and on to bikes.

This is arguably the legacy that Sky can most be proud of, and which will pass the test of time.

Even cycling's governing body, the UCI - whose president David Lappartient has clashed with Brailsford in recent times - congratulated the team for its support of cycling, and for having "contributed to the development of the sport".

However, while the team will be missed by its fans, many of whom believe that Sky only ever took advantage of the rules to give themselves a competitive edge, others may feel this news will give other teams a chance to compete, and could actually prove healthy for cycling after such domination.

It will be interesting to see what the end of Sky's sponsorship does for competitiveness in the sport, and for fan engagement.

And as well as being arguably the most successful current professional team in British sport, Sky are also among the most controversial and divisive.

Did the controversy play a role in Sky's decision?

We did not cross the ethical line - Wiggins

Possibly. Sky denies this. Brailsford says he is not aware it did. But it is hard to imagine that recent controversies were not a factor.

It is only a few months since a scathing report by a parliamentary committee of MPs concluded that Team Sky had "crossed an ethical line" in their use of medical exemptions for banned drugs after their therapeutic use exemptions (TUEs) were revealed by Russian hackers.

Even former coach Shane Sutton described Team Sky's use of corticosteroids as "unethical".

The team denied this, but the intrigue and suspicion surrounding a mystery jiffy bag - a medical delivery for Wiggins after a race in France in 2011 - the subsequent inconsistencies and inaccuracies in Sky's explanations, and the strange absence of medical records at a team renowned for extreme attention to detail were further blows to the brand.

Four-time Tour de France winner Chris Froome was cleared of any wrongdoing by the UCI shortly before this year's race after his adverse analytical finding for salbutamol last year. But given his status as one of the sport's greatest ever riders, the saga did further damage to the team's standing, as well as the wider sport.

Before he was cleared, organisers tried to bar the then-reigning champion from entering the race, and Lappartient, the most powerful man in the sport, told me that it would be a "disaster" if Froome competed without the case being resolved.

He later suggested Froome had effectively had his legal victory bought for him thanks to Sky's wealth.

But long before that episode, Froome and Sky had come under scrutiny.

Team Sky's dominance of a sport with such a tainted history of cheating was always going to make them a target. But so too did their promise to be an outfit the sport could finally be proud of. And subsequent events left them open to accusations of hypocrisy and of failing to live up to that pledge.

Two former Team Sky riders - Josh Edmondson and Jonathan Tiernan-Locke - both granted me interviews in which they made claims about the unethical use of controversial painkiller Tramadol while on the team's books. Edmondson even alleged his illegal use of injections had been covered up, all of which Sky denied.

And then there was a life ban for multiple doping violations handed to former Team Sky doctor Geert Leinders.

Ironically, the popular and humble Geraint Thomas' maiden Tour de France win in the summer was regarded as a much-needed PR boost. He is favourite to become the third British cyclist in the past seven years to win the BBC's Sports Personality of the Year award this weekend.

But there is more intrigue to come. Even as the news sunk in at Team Sky's Manchester headquarters at the national velodrome, across the city, the man at the very heart of the 'jiffy bag scandal' - ex-Team Sky chief medic Dr Richard Freeman - was creating more troubling headlines.

The medic pulled out of giving evidence on behalf of former rider Jess Varnish at her employment tribunal. She claims she was unfairly dismissed by British Cycling and is suing the governing body and UK Sport.

Freeman, meanwhile, is being investigated by the General Medical Council for a mystery delivery of testosterone to the velodrome in 2011. He now faces a very significant hearing into the case in February when he will be asked to explain the episode. In an exclusive interview with me in June - the first he gave after the jiffybag controversy erupted - the doctor vowed to clear his name. The sport will certainly be hoping he can do so. If he fails, it could cast a shadow over British cycling more serious than any previous scandal.

Who might buy Team Sky and what will happen to Brailsford?

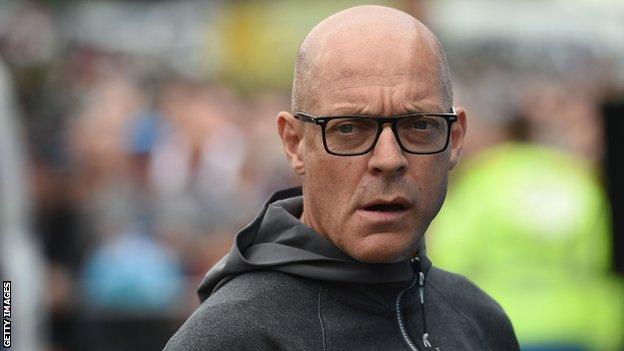

Sir Dave Brailsford said he feels a responsibility to the riders and staff to provide them a secure future

For several years, alongside Sir Alex Ferguson and Sir Clive Woodward, Brailsford was the nearest thing Britain had to a coaching guru. A recognised expert in the art of leadership and winning. One of the architects of the country's Olympic revival.

The controversies have undoubtedly diminished that reputation. But he retains respect in sport and in the corporate world, and it would be no surprise to see him employed by Sky in a senior role even if the team itself folds.

For now, however, he says he is committed to finding a new sponsor, and "adapting".

Certainly it will prove very difficult to find a replacement willing or able to match the levels of investment the team has enjoyed over the past decade. With uncertainty caused by Brexit, these are tough times in the sports sponsorship market. With no TV rights, and no stadiums to sell tickets for, pro-cycling teams are dependent on sponsors, and several are known to be struggling financially.

Having said that, changes of sponsor are nothing new in cycling, and Brailsford says he is optimistic and has already received calls from potentially interested parties. A defiant Froome has said the team is not finished.

Maybe a very wealthy individual - rather than a company - could come to the rescue. Tinkoff, BMC and Mitchelton-Scott are among the top cycling teams to have been bankrolled by millionaires. Brailsford says he will do what he can to find a replacement.

The jobs of the team's 100 members of staff, and the long-term contracts of some of the world's best riders, depend on it.