How David Beckham became a byword for marketability

- Published

- comments

David Beckham was not quite the outstanding British footballer of his generation. That his retirement is gathering such headlines across the world is a reflection not only of what he did on the pitch - which was an awful lot - but of what he became off it.

Beckham signed his first professional contract at a time when England footballers would still retire to run pubs or sell double-glazing. When he left the game, 21 years later, he did so as arguably the most famous footballer on the planet, the face of everything from soft drinks to supermarkets, perfumes to pants, football academies to entire overseas leagues.

No other British sportsman would have a welcome party thrown for him at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art with a guest list that included Tom Cruise, Will Smith, George Clooney and Oprah Winfrey.

Nor would their children have Elton John and Elizabeth Hurley as godparents.

No stranger to the headlines, Beckham's celebrity went up a notch when he moved to Los Angeles

For some that is no bad thing. Such relentless pursuit of profile and wealth is not everyone's idea of successful living. That an anagram of metatarsal, the foot bone he famously broke before the 2002 World Cup,, external is "a tart's lame" is almost too neat.

Yet that profile was founded not on empty hype but exceptional footballing ability. Beckham genuinely achieved: 19 major trophies including 10 league titles; the only English player to win championships in four countries; scoring or providing assists in more than half of his 534 top-flight games.

He could not beat a defender for pace, but he didn't have to - he would simply bend his crosses round them. He was an average tackler who seldom headed the ball, but possessed a right foot so precise and versatile that it was as if he had every golf club in the bag to hand - long drives, little chips, curving approaches, flighted dinks.

Paul Scholes, who retired just a few days earlier, was arguably a more complete midfielder. Liverpool fans will maintain a similar case for Steven Gerrard, Chelsea supporters for Frank Lampard. Ryan Giggs has won more and played longer for Manchester United.

So how has Beckham surpassed them all on the global stage?

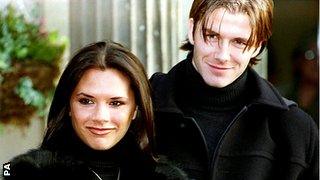

Beckham met Victoria Adams of the Spice Girls at a charity football match in 1997 and they married in 1999

He did not invent the template for sportsman as celebrity. But he and his advisors did establish new methods and new parameters. And in his wife Victoria he has had a campaign manager and cheerleader like no-one else.

England captains had married pop stars before. England stalwarts would marry them afterwards. But unlike Billy Wright, Beckham did so at a time when the media world was about to orbit celebrity like never before. And unlike Ashley Cole, he also generally managed to retain the nation's goodwill.

While his footballing career probably reached its zenith with the astonishing display against Greece in 2001,, external his commercial appeal accelerated even as his on-pitch talents gently waned.

He had already signed lucrative deals with Adidas, Pepsi and Brylcreem before signing to Simon Fuller's 19 Management in 2003, but those endorsements would multiply in scale and status over the following decade.

His haircuts, banal though it might sound, changed British fashion. A film that borrowed his name gave back a phrase to popular culture. You could travel to the most backwater village in as distant a country as Cambodia or Laos and still see posters of him stuck up in bars and restaurants.

Beckham's image brought him admirers worldwide

At times Beckham the brand has subjugated the footballer underneath. Last year a study from France Football magazine declared him the world's richest footballer, his estimated annual income of £28.3m more than that of Messi and Ronaldo even as less than 5% was generated by football wages.

So successful has this endless brand extension been that his name has become a benchmark for a sportsman's marketability. MS Dhoni is thus the David Beckham of Indian cricket, Andy Murray the next to seek Fuller's Midas touch.

Ever-present at his side has been perhaps the most influential presence of all, Victoria. His wife may have possessed no noticeable talent for singing, but in parlaying so little into such vast and lasting celebrity status she has revealed a strange sort of genius.

The two careers first intertwined and then became inseparable, each aiding and advancing the other's.

Ferguson may have believed that Beckham's migration into the land of fashion and entertainment diluted his ability on the pitch. But towards the end it also allowed him to extend his footballing career, his reputation beyond the sport and commercial status a significant draw for brand-conscious clubs.

No other British sportsman is as well-known around the world. No other could have pulled in the same publicity or glamour for London's successful Olympic campaign or even England's ill-fated World Cup bid.

Even those turned off by what they saw as mercenary mercantile pursuits could not dispute that Beckham maintained a remarkable standard of public behaviour in the face of relentless - if carefully orchestrated - media attention.

As a young man coming into the United team, he was impeccably polite to journalists, as far removed from the archetype of spoiled young superstar as it is possible to be.

The media training he subsequently received in a bid to give him more gravitas - think of the fingertips steeple he makes with his hands in television interviews, or the narrowing of the eyes for photographs - may have altered his image, yet he remained a genuinely nice bloke, even when the clothes or hair made him appear, at times, faintly ridiculous.

He also genuinely loved football - playing, watching, practising. In return he has been loved at some clubs, and appreciated almost everywhere else.

- Published16 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013

- Published17 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013

- Published31 January 2013