Roman Abramovich's 10 years as Chelsea's secretive Russian owner

- Published

- comments

What is Roman Abramovich's football philosophy?

As the secretive Russian billionaire has given just one unrevealing interview, external during 10 years at Chelsea, that's left for others to describe.

The popular image is of a ruthless and impatient owner, a man who has sacked nine managers and lavished £700m on transfer fees.

Yet Frank Arnesen, who worked for the 46-year-old for six years, says this isn't the man he knows. The Dane describes Abramovich as an owner who passionately believes in developing young players, wants his teams to play attractive football and is thoughtful and considered about everything he does.

Arnesen was chief scout and director of youth and development at Chelsea from 2005 to 2011 and talks of an owner who "would just show up at FA Youth Cup games, really enjoy them and then come and congratulate us afterwards".

This is the contradiction at the heart of Abramovich's Chelsea. On the one hand, Abramovich spent £20m on Chelsea's state-of-the-art Cobham training centre and academy, millions more to wrestle Arnesen from Spurs, and takes a keen interest in the progress of the club's young stars.

And the results have been impressive, with Chelsea featuring in four of the last six FA Youth Cup finals and producing a host of excellent young players.

Yet on the flip side, not a single academy graduate has established himself in Chelsea's first team during Abramovich's 10 years at the club, and they failed to field an English under-21 player during the entire 2012-13 Premier League season.

Abramovich's first manager, Claudio Ranieri, once complained that the Russian "knows nothing about football" and Arnesen admits that "when Roman came in he didn't know a lot about the game".

Yet he quickly adds that Abramovich is "a very intelligent man who put a lot of effort into learning about the game".

His mentor has been Piet de Visser, a 78-year-old Dutchman who was previously chief scout at PSV Eindhoven, where he was credited with discovering Brazilian legends Romario and Ronaldo.

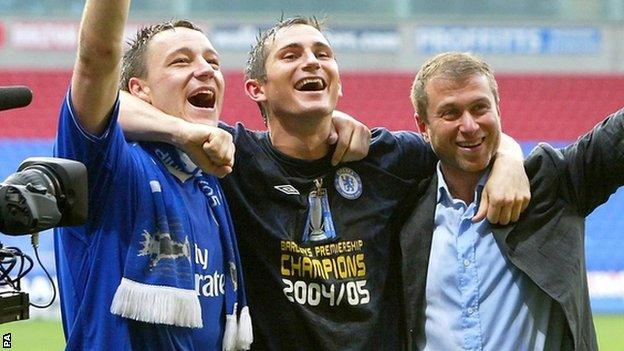

Abramovich brokered a £140m deal with Ken Bates to buy Chelsea on 1 July 2003

"Roman developed his knowledge of football through Piet," says Arnesen. "He was with him for weeks in the summer [of 2004], explaining formations, what he needed to be successful, that he had to start with the youth.

"He caught up very quickly and was very serious about it. He didn't want to just buy Chelsea and see how it would go. He was actually working very hard to catch up about football all the time."

It was De Visser who recommended Arnesen, then Tottenham's director of football, to oversee Chelsea's academy and scouting network.

Arnesen explains "Roman wanted to have the best academy and best scouting in the world and thought I was the man to start this up."

Under Arnesen, Chelsea were aggressive in securing the finest young talent in the world. They had a wrangle with Manchester United over the transfer of 18-year-old John Obi Mikel, external and had to compensate French side Lens after the controversial signing of teenager Gael Kakuta., external

The priority was to sign local players, but Chelsea's scouting network covered the whole world. They also wanted to develop English coaches and Arnesen says: "We had one Dutch coach in the first year I was there, but for the last five years we had only English coaches".

Teams from under nines upwards played the same way, and Arnesen and De Visser undoubtedly had great influence on Abramovich when it came to how Chelsea sides should play.

"We made a programme for the style of play, from under nines up," says Arnesen. "We were playing 4-3-3 with a number 10 [playmaker], learning to play from the back.

"I told Roman about my past at Ajax, for 18 years, then 18 or 19 years at PSV, and about my philosophy of football."

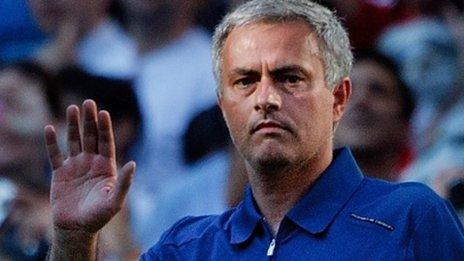

The influence of the Dutch duo created friction with Jose Mourinho, Chelsea's supremely successful manager who is now back at the club for a second spell.

Mourinho won back-to-back Premier League titles and two League Cups, yet Abramovich was unconvinced by some of his signings, frustrated by his sometimes functional style of play, and believed he should be giving more academy players chances in the first team.

In July 2006, Arnesen was handed overall control of transfers, which angered Mourinho, and the following year De Visser told a Dutch magazine:, external "Mr Abramovich is fed up that he has to keep paying millions and millions for big star players.

Jose Mourinho back at Chelsea - Abramovich's decade of bosses

"There comes a stage where you think it is pointless to spend so much, especially when it concerns players that Chelsea could develop within their own system or within their own youth academy.

"He had to pay an absolute fortune to get players like Didier Drogba and Michael Essien. This is why he has asked me as a private scout to look out for top-class young players who will be the Chelsea stars in three years' time."

Things came to a head in September 2007 when Abramovich, tired of Mourinho's outbursts, style of play and refusal to engage, external with his football advisers, decided to dispense with his Portuguese manager.

Avram Grant, Luiz Felipe Scolari and Guus Hiddink stepped into the manager's seat for short spells. A manager who is under pressure or on a short-term contract rarely looks to the longer term and bloods youngsters, which proved the case here.

The strongest tie-up between the academy and first team came under he stewardship of Italian Carlo Ancelotti, who joined the club in 2009 and won the double in his first season. At the start of the following campaign, he promoted four academy products - Kakuta, Patrick Van Aanholt,, externalJeffrey Bruma, external and Josh McEachran, external - to his first team.

Kakuta played 19 games for Chelsea's first team that season, Van Aanholt 18, Bruma 18 and McEachran 17, and academy manager Neil Bath said: "With Carlo's support and the board's support, we feel there is light at the end of the tunnel."

But at the end of the season Ancelotti was sacked, with Andre-Villas Boas and then Roberto Di Matteo coming in as manager. Chelsea realised Abramovich's dream of winning the Champions League, as well as the FA Cup, but the quartet's opportunities were severely restricted.

Bruma went on to join PSV Eindhoven and, although the other three are still at Chelsea, they all have been out on loan since the 2010-11 season.

Admittedly, another academy product, Ryan Bertrand, has tasted first-team action and even played in the 2012 Champions League final, but he has failed to fully establish himself in the side. Indeed the last homegrown player to become a first-team fixture is John Terry, blooded by Ranieri before Abramovich even arrived at Stamford Bridge.

Arnesen argues: "What it's about at the end of the day is the success of the team. You have to win trophies and this is what Chelsea have done under Roman. They have won the Premier League three times, the Europa League and the Champions League.

"He used his own money to invest, maybe £1bn, and you have to have a lot of respect for that."

Yet, as Chelsea themselves say on their own website,, external it goes deeper than that. "A successful academy has the potential to save the club millions of pounds in the transfer market [and] can also promote long-term loyalty and commitment among those players who make it into the 'big time'," it states.

We'll have to wait and see whether Mourinho can promote this in his second incarnation at the club - and whether Abramovich gives him the time to do so.

- Attribution

- Published1 July 2013

- Published3 June 2013

- Published3 June 2013

- Attribution

- Published9 November 2012