FA reforms must include improvement of grassroots facilities

- Published

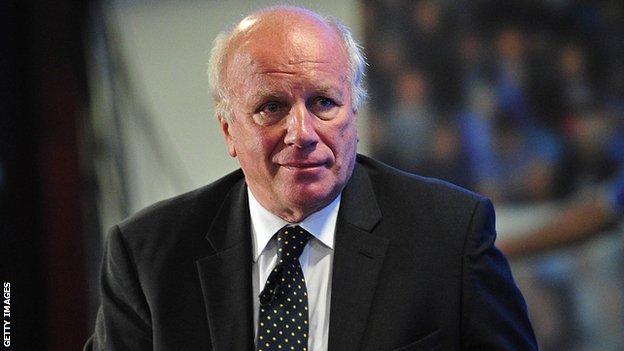

If Football Association chairman Greg Dyke's Commission really wants to study why fewer English youngsters are breaking through into the country's top teams, it may want to consider the importance of the facilities on which the next generation of footballers depend.

Inevitably the focus has so far been on the quality of youth coaching, academies, the numbers of foreign players in the English game, St George's Park, the Premier League's elite development pathway (EPPP), winter breaks and most controversially, the qualifications, colour and gender of the chosen few appointed to the panel.

But when deciding what reforms are needed to one day produce a better England team, the Commission should not neglect perhaps the most fundamental issue of all - the public pitches that children have to play on up and down the country. Especially when, as Premier League chief executive Richard Scudamore admitted so starkly this week, the state of those pitches is "woeful"., external

And when the FA, under pressure in its 150th year to come up with a way of reversing the decline in the numbers playing adult 11-a-side football, reveals that 84% of those who play the sport cite 'poor facilities' as their greatest single concern.

Wednesday saw the launch of the newly-named Premier League and FA Facilities Fund,, external which will hand out £102m over the next three years to grassroots infrastructure projects.

Previously known as the 'Football Foundation', the organisation which has overseen £1bn of spending on facilities since 2000, (and which will continue to deliver the funding), this investment guarantees that the current annual donations by the FA (£12m), Premier League (£12m), and Government (£10m) are maintained for a further three years from next year.

The rebranding has been done to satisfy the Premier League clubs, some of whom felt they should get more credit for the money they give away annually for local grassroots pitches for which they have no responsibility.

In reality this is of little significance, apart from a slightly reduced Football Foundation logo on the new buildings and pitches it will continue to build. More important is a new emphasis on targeting deprived, inner-city areas where the need is greatest, all-weather 3G pitches, and stronger links with the Premier League clubs and their existing community projects.

Some will argue this is all to be celebrated, that it is a whole lot better than nothing, and that Scudamore deserves credit for persuading his shareholders to maintain the amount they give away, especially when, by all accounts, there were fears not long ago that the clubs may pull their funding altogether.

After all, the argument goes, it's not for the top clubs to take on the job that central and local government performs in many other countries, such as maintaining grassroots pitches and facilities as a statutory priority, especially when:

the Premier League already gives away £45m to various 'good causes' each year, a lot more than any other league in Europe;

the clubs' priority has to be running successful businesses, especially at a time of Financial Fair Play, external regulation;

they already donate £1.2bn to the Exchequer in tax;

the FA puts only £12m a year into grassroots facilities from a revenue of £318m.

So why should the clubs pick up the slack?

Others will take a different view: that in the context of the Premier League's record £5.5bn TV deal (£1.9 turnover per year), and the staggering amounts leaving the game in terms of wages and agents fees, £12m simply isn't enough and is a lot less than the £20m that the three partners used to each put in annually.

The question of how much the clubs should contribute and redistribute is almost impossible to answer, dividing opinion in the game - and beyond.

At a launch event in Southwark, new Sports Minister Helen Grant said she was delighted by the Fund. "This money is going to do an awful lot of good up and down the country. Rather than picking and comparing we should be positive about what is happening.

"More money is going into sport now than ever before and more people are participating in sport than ever before. We are ambitious and we want more to be done."

Shadow Sports Minister Clive Efford, external was less impressed, telling BBC Sport: "The 1999 Football Task Force report recommended that the Premier League should invest 5% of their income primarily in grassroots sport.

"This is not happening. This is a freeze in cash terms and taking inflation into account, this is a cut compared to what was given to the Football Foundation in the previous three years.

"At the same time we have seen a tripling of the money for TV rights paid to the Premier League for the next three seasons. Football is not like other types of business. It is hard-wired to the communities that have sustained the game through generation after generation of supporters. It has a moral obligation to put money back into our communities at the grassroots."

Amid the inevitable debate over how much is enough, it seems constructive to agree on one thing: that this funding is vital, particularly in the very communities from which the country's footballing talent has traditionally been found - the inner-cities.

London has 16% of the country's population but just 3% of the football facilities. The entire city of Liverpool apparently has just one full-size third generation pitch, and that belongs to Liverpool FC. The FA estimates that 1.5 million adults and youngsters want to play but have nowhere to do so.

The Football Foundation reckons the £1bn it's spent since 2000 upgrading pitches and changing rooms equates to just 5% of what needs to be done to being the entire national infrastructure up to the standard of some countries on the continent.

Up and down the country matches are being cancelled, children are having to play on water-logged, muddy or even dangerous surfaces where skill and technique are rendered even harder to master, and then being put off from turning up at all by often having to get changed outside.

Think of the negative impact that has on the numbers who play the game, and the way the game is played. Think of the number of potential players lost from the sport, who could have gone on to become something special had they just had the chance to play on a decent surface, or had a pitch nearby to play on at all.

The need for the kind of support the Foundation has given grassroots sport has arguably never been greater. Today the Sport and Recreation Alliance, external published findings that show the average club spent £6,570 on outdoor facility maintenance in 2012, a 33% increase compared to what they spent in 2011.

Clubs also spent 38% more on water rates, 19% more on gas, 10% more on electricity and 20% more on business rates. This comes as 41% of clubs said that financial sustainability was a challenge they were currently concerned about or likely to face in the next two years.

The Football Foundation, external has found that when it upgrades or builds decent facilities, participation rates have jumped dramatically. And this is the crux. The FA and Premier League are beginning to realise perhaps, that putting money into facilities is not just a moral obligation that must be done out of a sense of duty, but that it is in their interests.

It will actually increase the chances of unearthing the next generation of professional footballers.

The clubs will benefit. And so will the England team.

- Published20 October 2013

- Published19 October 2013

- Published19 October 2013

- Published19 October 2013

- Published11 October 2013

- Published7 June 2019