Matthews Final: When Blackpool fulfilled Sir Stan's FA Cup dream

- Published

FA Cup finals have thrown up many iconic moments over the years.

A white horse named Billie dispersing crowds at Wembley, Ricky Villa's mazy run, Keith Houchen's diving header, 'The Crazy Gang' beating 'The Culture Club' or Ben Watson's stoppage-time winner for Wigan - each special to someone, somewhere.

But as footballing scripts go, you would struggle to top what happened under the old Twin Towers on 2 May, 1953. More than 60 years have passed, but the legend of 'The Matthews Final' lives on.

"Getting to Wembley is the biggest thing in football, but it especially was in those days," said Cyril Robinson, the last surviving member of the Blackpool team which beat Bolton 4-3 that afternoon.

"Nowadays they've got cups for this and cups for that. But in the old days, everybody wanted to win the FA Cup."

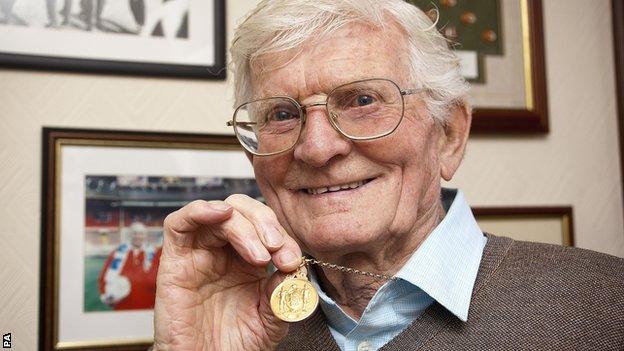

Cyril Robinson - the only survivor from Blackpool's team from 1953 - proudly displays his FA Cup medal

Beaten by Manchester United in 1948 and Newcastle three years later, Blackpool, who meet Bolton again in the third round on Saturday, had twice been FA Cup final bridesmaids. Never the bride.

An outside-right by the name of Stanley Matthews had yet to win the most prestigious prize in football at that time - an FA Cup winners' medal. At the age of 38, this was likely to be his last chance.

In the Bolton team was Nat Lofthouse, England's 'Lion of Vienna' who had scored in every round of that season's competition. He, too, had yet to win the FA Cup.

Even Queen Elizabeth II, a month away from her coronation, was in attendance.

Then there was the game itself. Blackpool trailed by two goals with 22 minutes remaining. But Stan Mortensen's hat-trick, which remains the only treble in an FA Cup final at Wembley, and Bill Perry's late winner sealed an astonishing comeback.

"It wouldn't surprise me if some had left the stadium at 3-1," admitted Robinson, now aged 84. "I was pleased for the supporters and pleased for myself because I would never get another chance of going to Wembley."

That Robinson was involved at all was a surprise, not least to the man himself.

He had played just a handful of first-team matches for the Seasiders and was only drafted into the starting line-up by Blackpool manager Joe Smith a few days earlier, as regular left-half Hughie Kelly had suffered a broken ankle in the penultimate league game of the season against Liverpool.

"We were playing Manchester City a week before the final and Joe said to me 'I'm going to put you in, and we'll see how you go'," he recalled.

"City won 5-0 because nobody wanted to get injured and they weren't at 100%, apart from myself. On the Monday before the final, Joe came up to me and said 'you're in on Saturday'.

"I didn't know what to think. My mind was going round and round. 'Is it true?' It was something I never expected.

"You don't get many chances, especially if you're a reserve, to play in a cup final. Luck was shining down on me and I got in. The chance to get in was a dream, and the dream came true."

But, perhaps understandably, much of the pre-match attention was on Matthews - one of the finest English players of his, or any, generation.

Matthews, aged 38 in 1953, had played in Blackpool's FA Cup final defeats of 1948 and 1951

Future England captain Jimmy Armfield, then a Blackpool reserve player, was in the stands at Wembley that day and played alongside 'The Wizard of the Dribble' during his early career at Bloomfield Road.

What was it that made Matthews so special?

"It was the nimbleness of feet," said Armfield, now 78. "And I never saw him out of breath. Despite his age.

"It was a deep-seated thing. His father was a boxer and fitness was in his life from the word 'go'.

"He also was a self-disciplined man. I would go down to the beach in a morning and I'd pick him up at eight o'clock. He would be there, all on his own, jogging."

Robinson added: "You couldn't compare him with anyone else. If he wanted to do a certain amount of training, he'd do it. A lot of it, he'd do it his own way.

"He used to run around with the crowd [of team-mates] when we were training, but at times he went out on his own near where he lived next to the sands. If he didn't feel like it, he wouldn't do it, but he trained very hard."

However, it seemed he would miss out on a winners' medal again when Bolton took control of the match in the early stages.

"We didn't click well in the first half and it wasn't going according to plan," said Robinson. "George Farm, a good keeper, made a mistake and the ball was in the back of the net. Catastrophe. 'How are we going to get out of this?'"

Lofthouse's early goal was cancelled out by Mortensen, but Bobby Langton put Bolton 2-1 in front at half-time. Then, more woe for Blackpool.

"Another catastrophe. They had an injured man [Eric Bell]. There were no substitutes in those days and he was hobbling around. A cross came in and what happens? The injured man heads the ball in.

"That made it 3-1. 'Run the bath'. We felt like coming off at 3-1. The man engraving with the cup was getting his tools out ready to put 'Bolton' on it. I'm thinking 'at least I've played at Wembley'.

"But something seemed to switch on and Blackpool started to play. The confidence seemed to be coming back."

Matthews and Mortensen - the two Stans were colleagues at club level and internationally with England

Suddenly, Matthews was seeing more of the ball and causing chaos in the Bolton defence. Wanderers were retreating at the sight of his fabled body swerve.

Mortensen capitalised on a goalkeeping error to reduce the deficit and then levelled in the dying moments, completing his hat-trick with a thunderous free-kick.

Armfield remembers it vividly. "We were right behind the goal. As soon as he hit it, I knew it was in. There was no swerve or anything. He wasn't noted for his piledrivers, as you might call them, but this thing absolutely flew in."

All square. 3-3. Time for a hero. Enter Matthews.

"He was still the danger man," said Robinson. "Ernie Taylor put him through, he beat his man and got to the touchline.

"It looked like 'Morty' was going to get another goal, but he couldn't quite reach it. If Stan [Mortensen] could have scored, he would have done. As it happened, Bill Perry was right behind him and knocked it in.

"'We've won it, we've won it'.

"It was the biggest thing in my life."

A month before her coronation, Queen Elizabeth II presented Matthews with his FA Cup winners' medal

The waiting was over. At long last, Stanley Matthews had won the FA Cup. The cheer when Matthews collected his medal from the Queen was as loud as the one that accompanied captain Harry Johnston lifting the trophy a few seconds earlier. Both were carried on the shoulders of their victorious team-mates as the celebrations began on the Wembley turf.

Given Matthews' Cinderella story, it is easy to see why the match would later bear his name. But Robinson is keen to point out that two Stans, not just one, were pivotal to Blackpool's success.

"How many people score three goals in an FA Cup final?" he asked.

The answer? Not many. No player has managed it since Mortensen, and there have been 60 finals since.

"But Stan [Matthews] had all the publicity before the game and the public were all hoping for Stan to win, obviously."

Captain Harry Johnston (l) and Matthews were both carried aloft by the Blackpool squad at full-time

The gains for winning were small for Robinson, who experienced the highest moment of his football career at the relatively young age of 24. A £20 win bonus and a cigarette lighter were all he received. Plus that treasured medal, of course.

When the sides meet this weekend the financial rewards for victory - prize money, television revenue and a possible meeting with a Premier League giant in round four - will be far greater.

But the pride of winning the FA Cup in 1953, the pride of being involved in one of the most famous finals in history, and the memories that come with it, are worth so much more.

Cyril Robinson was speaking to BBC Radio Lancashire's Gary Hickson. Jimmy Armfield was speaking to BBC World Service's Simon Watts. Both interviews were broadcast in May 2013 - the 60th anniversary of The Matthews Final.

"Witness: The Matthews Final" - a BBC World Service documentary - is available to listen to via the BBC iPlayer.

- Published11 May 2013

- Published8 December 2013

- Published7 June 2019