World Cup stories: Ghiggia - the 'ghost' who silenced the Maracana

- Published

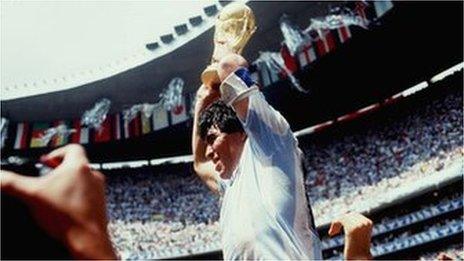

Great World Cup moments: 'The Maracana Blow'

Sixty-four years after scoring the World Cup-winning goal for Uruguay against Brazil at Rio de Janeiro's Maracana stadium, Alcides Ghiggia remembers with absolute clarity the moment nearly 200,000 spectators fell into a deathly hush.

"There was complete silence. The crowd was frozen still. It was like they weren't even breathing," he recalls. "They couldn't even raise their voices to cheer on Brazil. That was when I realised they weren't going to do it and that we'd won."

The slicked-back hair is thinner now, the pencil-thin moustache grey. But at 87, Ghiggia, the sole survivor from that 1950 winning team, is still recognisable as the pivotal figure of arguably the greatest upset in World Cup history.

Ghiggia waves to the crowd before attending a premiere of the documentary 'Maracana' in March 2014

Few expected a Uruguay victory. Certainly, no Brazilians did. A day earlier, São Paulo's Gazeta Esportiva newspaper proclaimed: "Tomorrow we will beat Uruguay!" Rio's O Mundo printed a photo of the Brazilian squad accompanied by the caption: "These are the world champions."

After a goalless first half, one minute into the second period Brazil took the lead through Friaca. But in the 66th minute, Uruguay's Juan Alberto Schiaffino equalised after connecting with Ghiggia's cross into the box.

The goal quietened the partisan crowd. But as victory in this World Cup was determined by points, rather than knock-out phases, a draw would still have seen Brazil crowned champions.

Ghiggia, a gifted right-winger in his prime, able to dribble the ball at great speed, has told the story of what happened next thousands of times. He tells it sparingly, matter-of-factly, with no sentimental indulgence.

World Cup: Brazil 1950 & Switzerland 1954

"I took the ball on the right," he recalls. "I dribbled past Bigode [the Brazilian left-back] and entered the box. The goalkeeper [Moacyr Barbosa] thought I was going to cross it, like with the first goal, so he left a gap between himself and the near post. I just had a second so I shot low between the keeper and the post."

The ramifications of that moment, 11 minutes from the end of the match, are still felt acutely to this day.

For Brazil the result was considered a national catastrophe. The match remains etched solemnly on the national consciousness as O Maracanaço (a Portuguese term roughly translated as 'The Maracana Blow', which became synonymous with the match). With just a touch of hyperbole, not to mention bad taste, the Brazilian writer Nelson Rodrigues referred to the defeat as "our Hiroshima".

Vilified by their fans, many of the squad slunk into retirement; others were never selected again. With the home strip, a white shirt with a blue collar, now considered jinxed, Brazil then adopted its famous yellow and green uniform. Five World Cup victories followed, but they have never fully erased the trauma of that defeat.

Barbosa, the Brazilian goalkeeper, never got over it. His miscalculation made him the obvious scapegoat. Despite a long career with the Rio de Janeiro club Vasco, he only played once more for the national team. Colleagues shunned him. After he was barred from visiting the Brazilian squad ahead of the 1994 World Cup, he told reporters, "In Brazil, the maximum penalty for a crime is 30 years; I've spent 44 years paying for a crime I didn't even commit."

Ghiggia at his home in Las Piedras, Uruguay

Ghiggia says he thinks Barbosa was blamed unfairly. "I spoke to him years after the World Cup. I told him football is 11 men against 11 men. Goalkeepers are always under-appreciated. You can play well the whole match, but you let in a goal and they blame you. My marker didn't stop me, why didn't they blame him? Barbosa died [in 2000] with the ingratitude of the Brazilian people."

No match in Brazil's football history has been as analysed as the Maracanaço. Every 16 July is a time of reflection and introspection. Last year, the 63rd anniversary was marked with the publication of "Dossier '50", yet another contribution to the publishing empire built on critiques of the defeat.

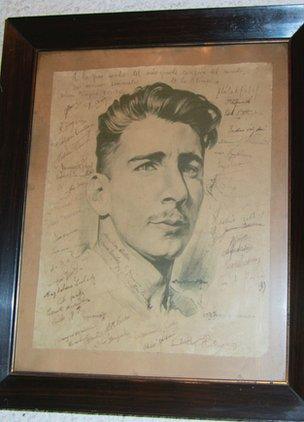

A drawing displayed at his home of Ghiggia at 24, signed by his World Cup-winning team-mates

Ghiggia has remarked previously that "sometimes I feel like I am Brazil's ghost. I'm always there in their memories."

Yet, given the pain he inflicted, the country's citizens seemingly bear him no ill-feeling. "They are always very affectionate towards me. Despite all that happened, people in Brazil still recognise me, they still come to talk to me about it. Recently, I was in Bahia for the World Cup draw and everyone treated me well."

Ghiggia travelled there from his home in the small city of Las Piedras, about an hour north of the Uruguayan capital of Montevideo.

Between two of its central streets, down a narrow whitewashed alley, the World Cup winner lives in a modest semi-detached bungalow, with his 40-year-old wife, Beatriz, and their large German shepherd dog.

On the walls of the front room hang the many trophies he collected in a career spanning 24 years, six clubs, and two countries. Above the fireplace is a line drawing of the player in profile, aged 24, signed by all the members of the Uruguayan squad. Opposite, an oil painting of the Maracana, as seen from above, on 16 July 1950, the day of their famous victory.

For Ghiggia, who scored in each of the four matches he played in that World Cup, the overriding memory is one of joy. "I remember the happiness that we felt. That's what I remember the most. The satisfaction of beating the whole world."

The celebrations, by today's standards, were modest. "We looked for the team treasurer but we couldn't find him, so we had a whip round among the players and bought some sandwiches and a beer. Then we went to the dormitory to celebrate." It was Uruguay's second, and last, World Cup victory.

Ghiggia remained in the Uruguayan squad for the next two years, but never added to his tally of international goals. In 1952 he left the Uruguayan side Penarol to become one of the first South American players to move to Europe, spending eight years at AS Roma in Italy.

In 200 league games Ghiggia scored 19 goals, though Roma never finished higher than third in Serie A during his time there. He became a naturalised Italian citizen in 1957, which made him eligible to play for the national side. The following year he was selected to play for Italy in the qualifying rounds of the World Cup; he scored one goal in five appearances, but it was the only time the Azzurri failed to qualify.

Did he feel divided loyalties playing for two different countries? "It was difficult, but I was also very proud. Of course my Italian inheritance qualified me, but it was something very special for them to select someone who had been born and brought up in another country."

After a short spell with AC Milan, Ghiggia returned to Uruguay in 1963, where he played six seasons for Danubio, before retiring in 1968, just days before his 42nd birthday.

Following their retirement from football, all the members of Uruguay's World Cup-winning team were given jobs by the government. Ghiggia's was to ensure gamblers did not try to cheat the Casino Montevideo. On leaving that post, in 1992, he was entitled to a state pension of around $700 a month.

To make ends meet, he moved from Montevideo to Las Piedras. He even sold his World Cup winner's medal, but a Brazilian-Uruguayan business magnate bought it and returned it to him. He supplemented his income giving occasional driving lessons. Beatriz, his third wife, was his first student.

Ghiggia was paraded around the pitch last November before Uruguay's World Cup play-off match with Jordan

Ghiggia's World Cup exploits did not make him rich, but he will be forever revered. His image adorned a special postage stamp on his 80th birthday with the words 'Ghiggia nos hizo llorar' ('Ghiggia moved us to tears'), and a mould of his feet lies alongside Pele, Eusebio and Franz Beckenbauer at the Maracana's walk of fame.

Brazil will play host to a very different World Cup this time, Ghiggia believes. "Before, football was more of a spectacle. It was friendlier, more beautiful. Now football is about business. There's a lot of money in the game. That's why football has changed so much."

But with Uruguay and Italy in the same World Cup group, alongside England and Costa Rica, he will have a keen eye on events.

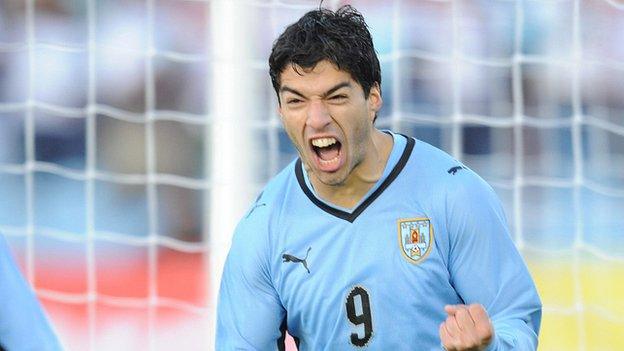

Ghiggia expects Uruguay and England to qualify - "Italy are not so good at the moment" - but despite a high regard for Liverpool striker Luis Suarez and Paris St-Germain forward Edinson Cavani, elsewhere he thinks the Uruguay squad is due an overhaul. "They will have to refresh the team," he adds. "There are a few of them who have been playing for years and they shouldn't be there anymore."

Maybe they are holding on for their own shot at World Cup immortality, their own moment to silence those who have dismissed their chances. Ghiggia, the great survivor, could tell them a thing or two about that.

- Published16 May 2014

- Published13 May 2014

- Published5 March 2014

- Published6 December 2013

- Published31 May 2014

- Published14 April 2014

- Attribution

- Published31 March 2014

- Published24 February 2014

- Published21 November 2013

- Published13 November 2013

- Published7 June 2019