World Cup 2014: The hunger of England captain Steven Gerrard

- Published

Steven Gerrard: England captain's World Cup highs & lows

What takes a skinny kid from No 10 Ironside Road, Huyton, Liverpool, all the way to a World Cup finals as England captain?

Plenty of lads grow up obsessed with football. Plenty do the training and dreaming. Some even have the ability. But it is hunger that propels the very few to the top, and it is hunger that defines Steven Gerrard.

It first emerged, night after night, in after-school street kickabouts on the Bluebell estate a quarter of a century ago.

After 110 caps and 14 years in an England shirt, that same drive - nurtured by key influences on training grounds and team buses, fuelled by past failings and recent disappointments - will reach its zenith in Brazil. Whether it can be satisfied is quite another matter.

"I remember the first time I saw him," says Dave Shannon, former Liverpool youth team coach, who invited a precocious eight-year-old down to the Vernon Sangster sports centre on Priory Road one winter's evening in 1988 after a tip-off from Whiston Juniors manager Ben McIntyre.

"He was smaller than most of the other lads. But the thing that stood out, along with his technical ability, was his desire.

"He was fearless. He ran everywhere. We were working with the likes of Michael Owen and Jamie Carragher, Rickie Lambert and Jason Koumas. Now Jason was a good player, but he was lazy. He didn't have the desire of Steven."

Gerrard has spent his entire career with his hometown club Liverpool since making his debut in 1998

What came instinctively was carefully cultivated by Shannon and his colleagues Steve Heighway and Hughie McAuley. Twice a week, for an hour at a time, Gerrard was inculcated with the Liverpool methodology - driving passes with the top of the foot, caressing and curling them with inside and outside, drilling a ball at the wall and then controlling and turning on the rebound in one movement.

Throughout it all there was always competition, always ambition. Think you're good? Do it better. Think you're the best? Try this.

"Us coaches would ping the ball at them, and the challenge was for them to control it first time and ping it back," says Shannon. "Then they would be pinging it at each other, everything a contest, Stevie not wanting Michael to look better, or Jason to take the mickey.

"We would always make demands. If you were getting ready and one passed the ball to you a little sloppy, you'd give it back and say, 'no, give me a proper pass'. The group would watch and soak it up.

"Kids want to please people - parents, teachers, coaches. So if you said to a kid, 'That's brilliant, you pinged that just like a Liverpool player' - it would stick.

"Players like Steven, when they're 13 or 14 and they become immersed in an environment like that, are affected. They look at the first team and think: I want some of that."

The driven youngster

Gerrard watched some of his contemporaries advance, others fall away. Koumas went to Tranmere, Lambert to Blackpool. Owen accelerated into the Liverpool and England first teams.

When his own chance came, it would initially be as an everyman, filling holes in a team being reconstructed by Gerard Houllier. Conscious of his friends' diverging paths, he was determined to go the right way.

"You could see instantly the energy and ability," says Gary McAllister, brought in by Houllier in the summer of 2000, external to add experience and class to a young side built around homegrown talent.

McAllister and Gerrard won the Uefa Cup together

"There was a rawness there, no doubt about it, but you could see there was a proper star in the making. His attitude was right. He had this drive to get better."

The 35-year-old McAllister acted as both midfield fulcrum and an unofficial mentor to his young team-mate. So keen was Gerrard to learn from the man 15 years his senior, he would run to the team bus to ensure he got the seat next to him on long journeys.

"I'd been around the block a little bit, had plenty of experience, and he was always looking to pick up stuff," says McAllister, who made almost 800 club and international appearances in his 22-year playing career.

"That's one of the reasons why he was outstanding - he was always so inquisitive. He wanted to pick people's brains. And like all good players, he has continued to learn, no matter how old he has become or how many games he's played.

"The thing for me was how willing he was to play anywhere for Liverpool. He played centre midfield, but he also played right-back, dropped in at centre-back, played in front of the back four, played wide right, played on the left of a four.

"Sometimes young players can get a strop on about playing out of position. But he just wanted to get in the starting XI. And that has stood him in good stead, because he got such experience at such a young age in different areas of the pitch.

"As a young guy he was also very vocal. Age did not hinder him there. It was his club. If there was anyone slacking, or anyone whose level had just dropped, Stevie wouldn't be shy in putting them right. And he commanded enough respect to do it because of his work-rate, the way he trained, the way he conducted himself during the week."

Part of that preternatural determination came from insecurity. Liverpool insiders will tell you that, far from being the indomitable leader of legend, Gerrard has often been stricken by self-doubt. He is a player who needs to feel wanted, who requires reassurance from those around him.

It is why, even when Liverpool took him and Owen to an under-18 tournament in Spain when they were just 13, he still felt the need to somehow prove himself.

"The thing we had to rein in was that he wanted to get stuck into everything," remembers Shannon.

"He would go into tackles or headers he couldn't win and come out worse off. We had to protect him from himself, because he was missing games with injuries that were self-inflicted."

The club eventually brought in Bill Beswick, the sports psychologist who would later come to prominence through his work with Steve McClaren's England regime, to help Gerrard cope.

But as he established himself in the first team, the problem resurfaced: where did the balance lie between career-defining commitment and reckless ambition?

What was enough? What was too much?

"Sometimes he should have jumped out of the way rather than going in full force to attack the ball," says McAllister.

"But that comes with experience. If it was a 50-50 there was no doubt that he was going to be there. On occasions he would go for things he had no right to go for."

The Liverpool match-winner

As Gerrard matured, so did his team-mates' understanding of how he worked and how they should work around him.

That ambition could be disconcerting to those alongside him. Blessed with the ability of multiple midfield stereotypes - distributor, box-to-box, winger, ball-winner - Gerrard's desire to do it all made him both the perfect partner and a constant challenge.

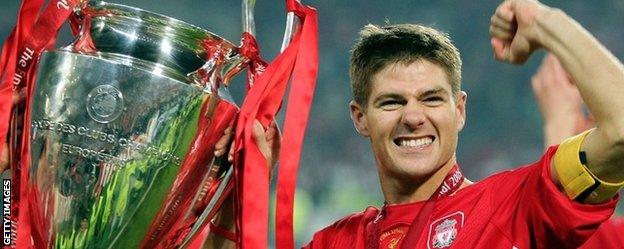

Gerrard inspired Liverpool to Champions League success in 2005

"When you play in the middle with someone, he makes you and you make him," says Didi Hamann, who won six major trophies in his seven years partnering Gerrard at Liverpool.

"Sometimes Stevie went into areas I didn't want him to go. But you had to let him have that freedom, because two minutes later he would be crossing the ball or scoring a goal from that position, and turning the whole game on its head.

"The whole team had to work for him, had to cover for him. Yet we were happy to, because if there was one player who could change a game for us, it was him. And those are the players who win you titles and trophies."

Hamann was in harness with Gerrard in the two matches that best represent his relentless resolve: the Champions League final of 2005,, external when Liverpool found themselves 3-0 down at half-time against AC Milan, and the FA Cup final the following year,, external when Liverpool trailed West Ham 3-2 with the 90 minutes up.

It wasn't Gerrard who delivered an inspirational dressing-room speech in Istanbul. That role fell to manager Rafael Benitez. But back out on the pitch, Gerrard's deeds convinced his team-mates the impossible might actually happen.

"If you want to win big games, you need match-winners," says Hamann. "And if you need to score three goals against one of the best defences of the era, you need someone to score the first.

"Stevie was the one who did that, who then won us the penalty to equalise. It was him at his best: bombing forward, causing problems.

"When his header went in - and the best headers of the ball in Premier League history would have been proud of that - we believed we could do it."

In Cardiff came arguably a greater performance. Gerrard set up Liverpool's first, scored the second and then crashed in the equaliser from 35 yards despite suffering from cramp so intense he was reduced to a jog.

"I was lucky to play with some great players," says Hamann, capped 59 times by Germany. "Michael Ballack was similar for Germany at the 2002 World Cup. But If you look at the impact Gerrard has had in big games, he has to go near the top of the tree. And we talk about these major finals, but he was doing this on a weekly basis: deciding games."

The unfulfilled international

And so we come to England.

For all Gerrard's achievements for his country - a debut the day after his 20th birthday, 21 goals, captain on 34 occasions; his country's leading scorer at the 2006 World Cup, their skipper at the next two - there is a sense he feels he has failed.

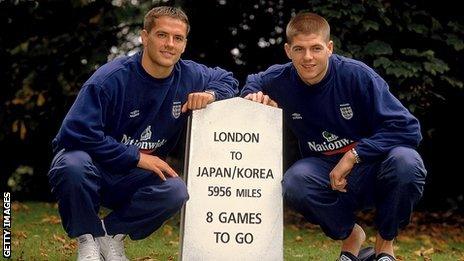

A groin injury ruled Gerrard out of the 2002 World Cup

Not once has he been beyond the quarter-finals of a major international tournament. He missed the 2002 World Cup through late injury, suffered penalty shootout defeats by Portugal at Euro 2004, external and the 2006 World Cup, external (missing his own spot-kick with England 2-1 ahead), and fell in the same fashion to Italy at Euro 2012.

"I don't feel I have done myself justice at a World Cup - I don't think any England player of this generation can think they have," he has said.

"If you spoke to the squad that came back after 1990, they could be satisfied with how close they came and that they did everything they could and had no regrets.

"But I have always come out of tournaments with England with regrets that we haven't gone to that extra stage, the last four or the last two. I take some of the responsibility for that. Penalty shootouts in the last eight are close, but not close enough."

Gerrard's England career highlights

As skipper of a young side in Brazil, Gerrard has both a responsibility and final opportunity.

Perhaps, had Liverpool not faltered in their pursuit of their league title, he might feel a little more sated, a little more at peace. Instead, with the Premier League title gone for another year, maybe for good, these next few weeks offer an alternative happy ending.

This being England - patchy in qualifying, consistent only in their ability to struggle in major tournaments - there are precious few guarantees. But the hunger will be there, just as it was on Ironside Road, just as it always has been.

- Published29 May 2014

- Published25 May 2014

- Published24 May 2014

- Published30 May 2014

- Published30 May 2014