World Cup 2014: How Belgium built their golden generation

- Published

Will Belgium's "golden generation" live up to their name at the World Cup?

Marc Wilmots likes to joke that he accepted the job of Belgium manager in 2012 because he had grown tired of commentating on World Cups without a team to support.

Those days have gone now, a lost decade consigned to history by a group of footballers dubbed 'the golden generation'. To English fans, it is a phrase that brings to mind unfulfilled promise, but for this Belgium squad it is a label that feels entirely justified.

Their match against Algeria on Tuesday may be their first in a major tournament for 12 years, but not only are they firm favourites to win a group also containing Russia and South Korea, they are regarded by some bookmakers and experts alike as dark horses to lift the trophy.

But how did a country with just 34 professional clubs spread over two divisions, manage to do that?

Belgium's re-emergence as a genuine footballing powerhouse has been put down to many different factors - sheer good fortune, a quirk of timing and immigration to name but three.

But there is a man who offers another, hugely significant reason.

"I had a plan to change the way we did everything," Belgium's former technical director Michel Sablon, told BBC Sport.

"We needed to start again. At first it did not make me popular, but back then we had almost been forgotten as a football nation."

Sablon was there to witness Belgium's first wave of brilliance in the 1980s. He was part of the national team coaching staff during an era when the likes of Enzo Scifo, Franky Vercauteren and Jan Ceulemans took Belgium to the semi-finals of the 1986 World Cup,, external losing to eventual winners Argentina.

They reached the last 16 at the 2002 World Cup, but that came on the back of their failure to qualify from the group stage at the 1998 World Cup and at Euro 2000, where they were co-hosts.

"The people of Belgium were beginning to question the team," Sablon said. "After Euro 2000, there was a feeling of embarrassment, the relationship was not good."

So when did things begin to change? In September 2006, Sablon started to write down a plan that would revolutionise Belgian football.

First, inspired by research trips to the best training centres in France, the Netherlands and Germany, every youth team in the country was told to play a fluid and flexible 4-3-3 formation favoured by the national team. Sablon made a brochure and went to clubs, schools and all youth coaches and told them how to do it.

"It wasn't easy to go to people and tell them to stop doing what they'd done for years," added Sablon.

Michel Sablon, Belgium's former technical director, revolutionised Belgian football with a brochure that he took into schools.

It took time, but Sablon got his message through.

Secondly, youth teams were no longer to focus on results. Sablon commissioned a study into youth football that saw 1,500 matches filmed and studied. One of the key findings was that too much emphasis was being placed on winning and not enough on developing players. It was win at all costs and that was costing Belgium.

Sablon even went as far as ensuring under-seven and under-eight teams did not have league tables.

"Results went out of the window," Sablon said. "The objective of the youth teams was no longer to win games, it was to develop players. It was not easy, I was personally attacked in the press and by people in the Belgium federation."

Thirdly, Sablon created a rule that once a player had moved up, for example, from the under-17s to the under-19s, he did not go back. Not even for crucial games.

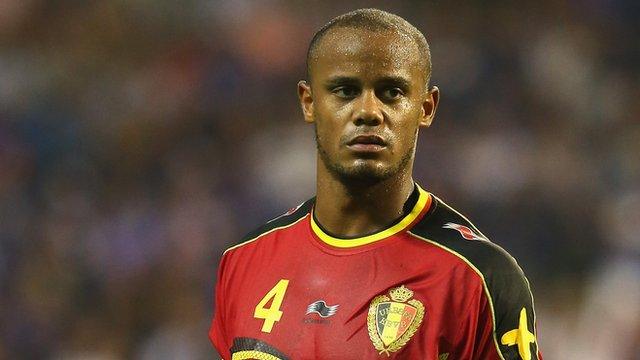

"I wouldn't allow it," he says. "I will give you one example. Vincent Kompany played perhaps two games for the under-19s, three games for the under-21s and then he went straight into the national team. We never took him back even to play in the biggest games.

"Once they made the step up we felt they should improve at that level, not come back."

And then something strange happened. In 2009, three years after the plan was formed, the results of the country's youth teams began to improve, just at the time the players had learnt not to focus on winning or losing, but simply improving.

"We found that our teams, even though it wasn't our target to be there, went from being ranked in the 20s to the top 10 in the 17s and the under-19s," Sablon adds.

"You want to know why? It was simply down to the development plan - we were making players better. The objective was not to move up the rankings but the result of having a better system meant that we did anyway."

The most promising youngsters were brought together to train at eight centralised, government-funded training schools. The best trained with the best and got better - and then went back to train with their clubs, further disseminating the new ideas.

This system produced Napoli forward Dries Mertens, Zenit St Petersburg attacker Axel Witsel, Tottenham midfielder Mousa Dembele and Liverpool goalkeeper Simon Mignolet.

"Having so many good players playing together from a young age was important," Mignolet told the BBC. "And now you look at our squad and so many of them play in big leagues for big clubs. That gives us all the confidence that we can do anything. That certainly had a big part to play."

Belgium's rise to prominence has coincided with their best players leaving their home countries for major foreign leagues.

Six years ago, Kompany was one of two Belgians in the Premier League. The other was Carl Hoefkens, a journeyman full-back, who had helped West Brom to promotion the previous season. These days, the list of Belgians is much longer.

"Five or six years ago no one wanted to give a chance to a Belgium football player in England or in the Premier League," Mignolet added. "Since the likes of Vincent Kompany, Thomas Vermaelen and Marouane Fellaini went over, they have shown to clubs and to the outside world that Belgian football players can succeed at the top level.

"Since then, English and Spanish clubs are more likely to give Belgian players a chance. Now that so many of us play at a high level, it follows that the national team will improve and we'll have the confidence to do well for our country.

In 2008, Vincent Kompany was one of only two Belgians playing in the Premier League.

"Our job now is to ignore what everyone else is saying and get out of the group."

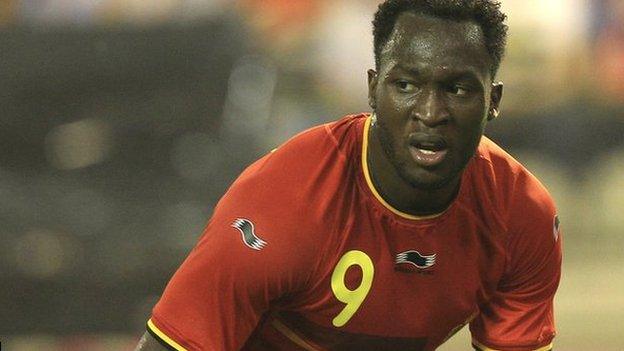

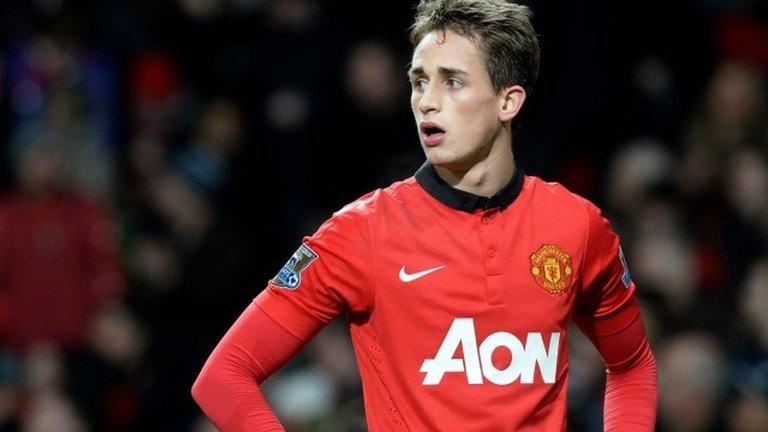

They should achieve that comfortably. This is a team boasting attacking talents such as Manchester United's Adnan Januzaj, who committed himself to the cause once World Cup qualification had been secured, and striker Romelu Lukaku. But another Chelsea player, Eden Hazard, is the one player of whom the most is expected.

Georges Leekens, who managed Belgium from 2010 to 2012 and is now in charge of Tunisia, believes Hazard's growing maturity will stand him in good stead.

"At the age of 19, he was at Lille and the best player in France, but I felt he could be much, much more," says Leekens. "In the beginning I was a little bit hard on him.

Belgium's Premier League players | |

|---|---|

Player | Club |

Thibaut Courtois | Chelsea |

Thomas Vermaelen | Arsenal |

Vincent Kompany | Manchester City |

Jan Vertonghen | Tottenham Hotspur |

Marouane Fellaini | Manchester United |

Romelu Lukaku | Chelsea |

Eden Hazard | Chelsea |

Kevin Mirallas | Everton |

Simon Mignolet | Liverpool |

Mousa Dembele | Tottenham Hotspur |

Adnan Januzaj | Manchester United |

Nacer Chadli | Tottenham Hotspur |

"Everything he was doing in France was fine but it was too easy for him. We fell out. I said to him 'Eden, I have picked you 20 times, but you can be more than this. You can be more responsible.' A manager can only make 2% or 3% of difference," said Leekens.

"The rest is down to the player. Eden has taken responsibility and that is maybe the most important thing. He is a big player and a big man as a human being.

"The move to Chelsea was the best thing that could have happened to him. Before he moved to England, he loved the game, he loved the ball. Now he loves the team and he loves to win. He could be a match-winner in Brazil."

On paper, Belgium have the ability to compete with the very best, but at this level they remain untried and untested.

However, Wilmots, a former midfielder for Standard Liege and Belgium, is not looking beyond Group H. "We have everything to lose up until then," he said. "After that, we'll have nothing to lose."

At least he no longer has to endure watching World Cups that do not involve Belgium. Now he must shoulder a different burden - how to ensure this golden generation fulfils their unquestioned potential.

Eden Hazard has 45 caps for Belgium despite only being 23 years old

- Published15 June 2014

- Published16 June 2014

- Published10 June 2014

- Published18 June 2014

- Published8 June 2014

- Published23 May 2014

- Published23 April 2014

- Published6 December 2013

- Published7 June 2019

- Attribution

- Published12 June 2014