Les Ferdinand on vans, loan deals & his part in the rise of Harry Kane

- Published

QPR owner Tony Fernandes appointed Les Ferdinand as the club's director of football in February

Les Ferdinand is sitting in his office at QPR's Harlington training ground in his club tracksuit, straight from a stint with the players.

He is a director of football whose heart is still out on the pitch, and he casts his mind back almost three decades to the opportunity he was given when he first set foot in the club as a new boy plucked from non-league.

He chuckles as he recalls telling the QPR manager in 1987, Jim Smith, that he couldn't join straight away as he had to work his month's notice as a van driver.

"I remember there were some guys who were just about to be released," Ferdinand, 48, recalls.

"They were saying, 'do you know, I might go and play non-league football. Two nights' work and still get paid £150 a week for playing'.

"I said: 'Are you guys mad? Are you seriously saying that? You have got to try your nuts off to stay in football! You don't believe what you have got'."

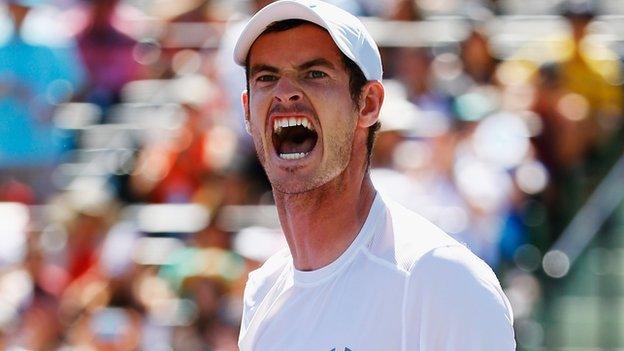

Ferdinand made his England debut in 1993. He went on to win 17 caps over five years, scoring five goals

'We gave Kane, Mason & Townsend a chance'

The former England striker is a man with a stock of stories to tell about the precarious business of opportunities in the game: how they come about, how they can so easily slip through a player's fingers, how they can be nurtured - and seized.

Reflecting on his own playing career and coaching experience, his is a voice worth listening to carefully at a time when Football Association chairman Greg Dyke is trumpeting ideas to find a host of English players like Harry Kane.

Ah, Harry Kane. Having watched Kane and his Tottenham team-mates Ryan Mason and Andros Townsend celebrating together for England in Turin during the week, Ferdinand argues that the line between that happy picture and talent drifting unharnessed in the modern game could not be thinner.

Kane, Mason and Townsend came through the development squad together at Spurs under the tutelage of Ferdinand, current QPR manager Chris Ramsey and Aston Villa boss Tim Sherwood.

"But I guarantee you now, had Tim, Chris and myself not taken over the first team, nobody would be talking about Kane, Mason and Townsend. Because we gave them the opportunity to play," stresses Ferdinand.

Ferdinand's Spurs proteges Harry Kane, Ryan Mason and Andros Townsend celebrate for England

"They would not be playing at Tottenham otherwise. Andros went out on nine loans. Harry had four loans. Mason had five loans. They were no nearer the first team when they came back than when they went out on loan. It was only that we had been working with them and we knew we could put them in the first team and trust them.

"The average lifespan at any club for managers now is 11-12 months maximum. They haven't got time to think about player development."

For all the talk of quotas to clear the pathway for youngsters, as far as Ferdinand is concerned there is a much more immediate problem for players getting stuck in the system. It's that critical age between 16 and 21 that Arsene Wenger pinpointed this week.

"That's the heart of the problem," said the Arsenal manager. "Let's get better at that level, then if there is a problem integrating those players in the top teams, we have to do something about it. Today you have to be very brave to integrate the young players because the pressure is very high."

Ferdinand was part of the management team that took over from Andre Villas-Boas at Spurs in 2013

That sentiment strikes a chord with Ferdinand. He understands why managers are loath to take a risk on a young player. But the system, he reckons, makes it extra difficult to take those risks. Why? Because youngsters at the top clubs are starved of competitive football at the highest level.

The under-21 league, introduced by the Premier League as part of their Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP) in place of old-style reserve-team football, is far too sterile for his liking. Ferdinand would scrap it in a heartbeat.

"It's not competitive enough," he says. "Look at our squad. For the previous manager here [Harry Redknapp] if there was a problem in the first team he wasn't looking at the under 21s. He would rather go and take someone on loan who he knows has played competitive football against seasoned pros.

"That's what 99% of managers in the Premier League would do. They don't see the under-21 squad as being competitive enough, which is why these boys are not coming through."

Reserve team football is 'messed up'

Ferdinand recalls his early days as a QPR player whisked out of non-league football.

"My first reserve game we had Clive Walker, Sammy Lee... all these experienced professional players. We played Southampton and they had Jimmy Case playing." His expression reveals that was an early lesson to the physical demands required. "I am not going to get better experience than that. I am certainly not going to get it in the under-21s.

"These people helped you, they guided you through your football. In the under-21s if you have another kid telling you to push in here or there, they are not quite sure what they are doing.

"The other thing that happened is if you didn't play on Saturday you knew you were playing on Tuesday in the reserves, it didn't matter how big a player you were. And they didn't have the hump because it wasn't seen as a punishment. It was about keeping yourself fit to play football.

Ferdinand made his QPR debut, aged 20, in a 4-1 defeat against Coventry City in April 1987

"Nowadays the senior players in the under-21 development games see it is a punishment. They don't want to play. So they end up not running around as they should do.

"Because I worked in under-21 football I understand that these players need to be given an opportunity. Otherwise you just have a creche. It is a bit messed up. They have to look at the whole picture."

Given the complicated mix of stifled opportunity plus a generous salary - and all that at a sensitive age in between the teens and being a young adult - it doesn't seem to be the most productive environment.

'It was the making of me as a footballer'

Intriguingly, when Ferdinand looks at his own chance as a young player, he admits he found it difficult to get his head around what was happening - and that was without agents in his ear and megabucks in his pocket.

One day he was at Southall and Hayes, training twice a week after work and playing on the weekend. The next he was in the professional game.

Ferdinand's career in numbers | |

|---|---|

11: Number of clubs (Hayes, QPR, Besiktas, Brentford, Newcastle, Tottenham, West Ham, Leicester, Bolton, Reading, Watford). | 19: Goals he scored in 30 games on loan at Besiktas as the first Englishman to play in Turkey. |

212: Domestic goals in all competitions. | 1: Appearance for England B in a international against Russia B in 1998. |

17: England caps, with his debut coming in a 6-0 win over San Marino in 1993. | 29: Most goals in a season, for Newcastle in 1995/96. |

5: England goals, the last of which came in qualifying for France 1998 against Georgia. | 0: The number of appearances he made for Watford in 2005/06 after arriving on a free transfer. |

"Instead of doing it for fun, suddenly it was my job. I struggled with that for a while," Ferdinand says. "I needed to change my lifestyle and I didn't. I was a young kid from a council estate and was still running around with the guys I had been running around with before I joined QPR. It all happened very quickly.

"It took a while to adjust to the life of being a professional footballer. The truth is I probably didn't adjust to it until I went to Turkey, to Besiktas on loan in 1988.

"It was amazing not only as a football lesson but as a life lesson. I was on my own, the first British player to go to Turkey, in this environment I totally didn't know about. But I needed to do it.

"I realised I did want to be a professional footballer and I needed to get away from distractions and concentrate 100% on football. That's what Turkey allowed me to do. It was the making of me as a footballer. I feel that was me serving my apprenticeship."

Ferdinand moved to Newcastle in 1995 for a £6m fee. He scored 50 goals in a two years on Tyneside

Ferdinand is a big believer in loans as long as the player himself is in the right mindset.

"People often go on loan and think, 'I'm here for a month. If it doesn't go that well it doesn't matter I'll go back to QPR or Arsenal or Tottenham or wherever. I don't really want to be here anyway…'"

But players need to believe that loan will actually lead somewhere, rather than feeling they are just farmed out.

The 22-year-old Ferdinand returned to QPR from Besiktas in 1989 - having scored 19 goals in 30 games - and never looked back. He was one of a generation that also included Ian Wright and Stuart Pearce that made the full journey from non-league to an England shirt.

'Non-league boys appreciate what they have'

The current crop of Premier League players who have their their roots in non-league - the likes of QPR's Charlie Austin, Burnley's Danny Ings, Dwight Gayle of Crystal Palace, Liverpool's Rickie Lambert and Jamie Vardy of Leicester - prove that the EPPP is not the only way to mould top level players.

"Coming in here to work every day is much better than getting up at 6am, working all day, having to jump on two trains and two buses to get to training," Ferdinand adds. "The boys that come out of non-league appreciate what they have."

Rickie Lambert has won 11 England caps having started his career with trials at non-league Marine

That's another big part of the development issue - today's youngsters in the academy system are so well looked after their hunger can be eroded.

"That's a conversation that has been going on for many, many years," says Ferdinand. "How do we change the mindset of boys that have been brought up in the system because they believe this is life? It is their life. It is what they have got used to. So it's very difficult to tell them about another way when that is all they have seen.

"I know at all clubs education has become a major part of what they do. But it doesn't really give you the life experience. Maybe sending them out to work for a few months, to get up at six in the morning or maybe even earlier to go and do a day's work, might help them to appreciate what they have got."

Ferdinand laughs at such old-fashioned idealism in the middle of modern, £5bn industry. But it is an interesting idea.

Anything and everything needs to be taken into consideration in the hunt for the next batch of Harry Kanes.

- Published3 April 2015

- Published3 April 2015

- Published4 April 2015