Is a big ego crucial to achieving sporting greatness?

- Published

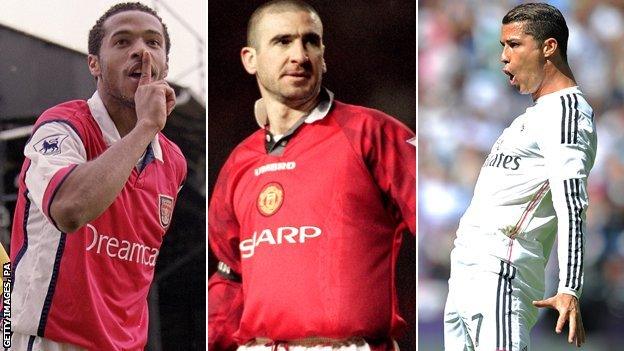

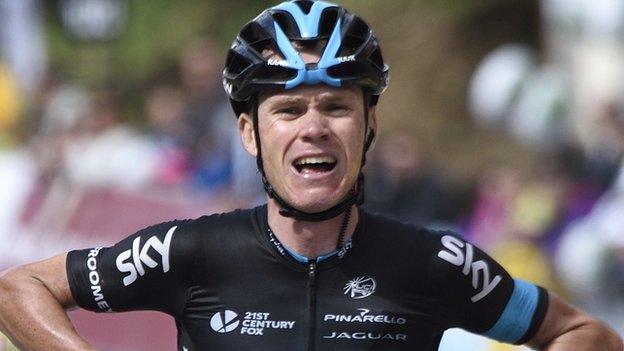

Henry, Cantona and Ronaldo all possess the ego to help them maximise their potential

One evening in the mid-1990s, Manchester United players and staff attended a Batman film premiere. It was a black-tie event.

United star Eric Cantona had other ideas and arrived wearing an all-white suit finished off with bright red trainers. His team-mates laughed, while manager Sir Alex Ferguson turned a blind eye.

Cantona was a talent with an abundance of self-confidence, but had been a destructive force inside the dressing rooms of his previous clubs in France. He had been known as much for punch-ups with team-mates at Auxerre and Montpellier as his ability with a ball at his feet.

Eric Cantona: When Football Focus met 'King Eric'

He was perceived as damaged goods in France, but in England he helped Leeds United win the league and after his arrival at Old Trafford in the autumn of 1992, he was afforded the freedom to express his eccentricities because of the example he set on the training ground.

Cantona was one of the first players under Ferguson to spend hours after a session practising the basics on his own. He was humble enough to acknowledge his flaws and, as captain, help the younger players rid themselves of theirs.

But he always maintained a swagger that saw him hold his nerve under pressure to produce moments of match-winning brilliance when his team needed it most, such as the winning goal in the 1996 FA Cup final against Liverpool.

His is a story that prompts an interesting question. While physical gifts and world-class skill are key to the success of sport's finest athletes, is a big ego - defined in this case as a supreme level of self-confidence - the secret ingredient that elevates good to great?

'Messi and Ronaldo both have egos'

Mike Forde is a firm believer in the power of ego. He spent eight years as performance director at Bolton Wanderers between 1999 and 2007 and a further six as director of football operations for Chelsea.

His jobs involved travelling the world liaising with sports teams - from the All Blacks to NFL and NBA franchises. His quest was to identify innovations in areas such as psychology, IT, scouting and people management.

The definition of ego |

|---|

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the ego is defined as "a person's sense of self-esteem or self-importance". The term derives from Latin, literally 'I'. |

Forde told BBC Sport: "If you're Didier Drogba taking a penalty in the 2012 Champions League final, with 160 million people watching around the world and 60,000 stood in the stadium, you need a high level of confidence and self-belief to perform. That is what we characterise as ego."

Sports psychologist Bill Beswick, who has worked for Manchester United and England, adds: "Ego is very powerful and can be the driving force behind performance. Ex-Manchester United midfielder Roy Keane had intense self-belief. He maximised his ego to make the absolute best of himself."

Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi have won the prestigious Ballon d'Or a combined five times

But how do we know the greatest athletes possess this trait? We've seen ego manifest itself in Cantona's upturned collar, while Thierry Henry would often raise his finger to his lips when he scored.

Both were theatrical displays of inner confidence, but in others the same levels of ego are masked.

Confidence coach Martin Perry - whose clients include Arsenal midfielder Aaron Ramsey and golfer Colin Montgomerie - cites the difference between Barcelona forward Lionel Messi and Real Madrid's Cristiano Ronaldo.

"Ronaldo is very outwardly confident, whereas Messi comes across as quiet and humble, but both have egos. We know that because of the individual manner in which they play," he says. "They don't see risks; they have a bulletproof certainty they'll produce and when an athlete has that supreme level of confidence, magic can happen."

Fine line between good and great

West Brom goalkeeper Ben Foster often tells a story to youngsters at the club about one of his first training sessions after he joined Manchester United in 2005, external that illustrates how ego can dictate success or failure.

Foster made 12 first-team appearances in five years at Old Trafford but has gone on to have a successful career, first with Birmingham City and then at his current club West Bromwich Albion

Foster moved to Old Trafford from Stoke at 21 and was tipped to become a future England number one.

But as he looked around the dressing room and saw the likes of Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes and Wayne Rooney tying up their laces, he was overcome by a lack of self-belief and thought the club might have made a mistake in signing him.

Foster left United five years later having failed to make his mark and has since used a sports psychologist to learn techniques to erase self-doubt.

It's a story that resonates with Perry: "Ordinary levels of confidence don't allow you to do extraordinary things; greatness can't be achieved without it.

"Most magical moments in sport come from a place of supreme self-confidence - these are the moments which last forever and create legacy and legend."

When egos go wrong

Ego must be harnessed correctly to ensure an athlete steers clear of controversy and continues to develop.

"We often find in team sports that an athlete doesn't appreciate the affect he is having on the rest of his team by acting in a certain way, which can cause arguments," adds Beswick. "Under pressure, athletes can change from 'we' to 'me'. That happens a lot."

Only four England internationals have scored more Test runs than Kevin Pietersen, but he may never get the chance to write the final chapter of his story now he is in the international wilderness following disputes with members of England's cricket team.

Prince Naseem Hamed (r) won the IBO world featherweight title fight against Manuel Calvo in 2002

Prince Naseem Hamed, external was the world's best featherweight boxer between 1997 and 2000. But one wonders how much more he could have achieved had he not become lost in the fog of his own hype and cut corners in training, resulting in the only defeat of his career to Marco Antonio Barrera in 2001 and subsequent retirement, aged just 28, in 2002.

Sport psychologist Steven Sylvester, who has worked with England cricketer Moeen Ali, two world champion snooker players and a major-winning golfer, among numerous other athletes, cites the problems caused when a sportsman or sportswoman adopts a selfish approach.

"That mindset is a catastrophe for me," said Sylvester. "We want athletes to make the right decisions on the pitch under pressure and think how they might benefit their team-mates rather than just themselves. "

'Don't dispose of big egos'

As the example of Cantona shows, life experience can manipulate ego over time and provide the catalyst to fuel genius rather than conflict.

Forde adds: "I've seen players who were very egotistical or arrogant and then they'd get married or have a baby and you'd see a change in their personality.

"You have to look at an individual sometimes and say 'we're going to sign this guy for three years, we know there's a certain level of risk, but he's reaching a point in his life where the penny might drop. So are we prepared to take that risk or not?'"

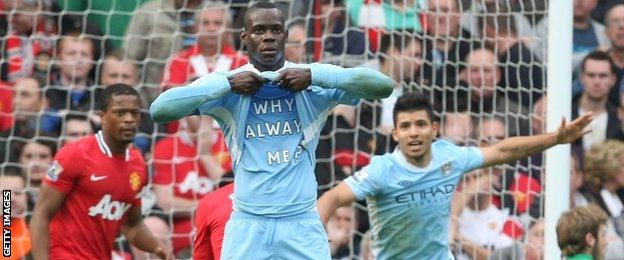

It's a dilemma Liverpool boss Brendan Rodgers faced before opting to sign Mario Balotelli from AC Milan last August following his well-documented problems, although he is still waiting for his investment to pay dividends.

Balotelli revealed a T-shirt that hinted at his ego after scoring in Manchester City's 6-1 win over derby rivals United in 2011

At Bolton and Chelsea, Forde helped to develop an ethos that saw both clubs pursue what he calls "big ego talent".

The likes of Juan Mata and Eden Hazard arrived at Stamford Bridge during his tenure, while Nigeria legend Jay-Jay Okocha, Spain's fourth highest-ever goalscorer Fernando Hierro and France World Cup winner Youri Djorkaeff were signed by the Trotters.

His policy at Bolton was one that went against conventional wisdom. Okocha, Hierro and Djorkaeff were all in their thirties and past their physical peak, with no sell-on value, but crucially they all had one thing in common.

"The key isn't to dispose of big egos. The real question is: is that ego manageable? Is it coachable? Are they humble enough to continue to learn?" explained Forde.

"I remember having dinner with Fernando Hierro. He was 35 at the time, had played 90 times for Spain and won the Champions League twice. I asked him 'what's been the highlight of your career?' He put his knife and fork down and looked at me and said 'I haven't had it yet'."

The formula for greatness

When talent and ego are in perfect symmetry, a player can make the leap from good to great.

Forde uses a formula - (ego + coachability) x learning culture - with high-performing teams and individuals to help them maximise their talent.

"The equation shows that ego is the foundation of greatness but only if it is still open to being coached and criticised and there's a structure in place to help them grow," he said.

It is an equation that explains the success and longevity of some top sports stars.

"I look at Frank Lampard, that's why he's playing at the age of 37, then you go into North America, a LeBron James of the NBA or a Tom Brady at the New England Patriots or a Derek Jeter at the New York Yankees.

"The ego is in place to give them the confidence to perform on the biggest stage and then there's coachability and this intrinsic DNA that gives them the desire to be the best version of themselves.

"If that's in place, greatness can appear."

- Published25 June 2015

- Published25 June 2015

- Published25 June 2015

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019

- Published2 November 2018