Pre-season: Running to the point of exhaustion

- Published

How hard is footballers' pre-season?

Profusely sweating, panting for air and feeling lunch turning in my stomach - I thought to myself 'Why did I volunteer for this?'

A feeling every professional footballer has when thinking about pre-season is pure dread - even while the tans are being topped up on a beach far, far away from a sweaty British gym or open field.

Just how hard can it be, though? Are they just overpaid moaners or are they athletes pushed to their absolute limit?

To find out, some idiot from BBC Sport (me) did the same test many footballers up and down the country are doing for their fitness.

I'm a 24-year-old occasional runner, casual cyclist and failed box-to-box midfielder with severe weaknesses for chicken wings, chocolate milkshake and custard doughnuts.

That makes me decidedly 'average' with a body to match - a perfect comparison between the everyday individual, whatever that is, and finely tuned athletes.

Test day

With trepidation, I travelled to the University of Essex on one of the warmest weeks of the millennium to take a test "to the point of exhaustion" alongside players from League One side Colchester United.

The test I did was very similar to the notorious VO2 Max test,, external in that you run on a treadmill with incremental speed increases until you can literally go no longer - the only difference being I was not wearing a Bane-like oxygen mask, external so would not find out what my VO2 Max was.

"The players don't like it because they don't want to be taken out of their comfort zone," said U's sports scientist Stefano Russo.

"But for us, we get to see blood lactate measurements which we can compare to the end of the season to see where they are at and what they've been doing.

"We also measure their maximum heart-rates so we can monitor their training and make sure training loads aren't pushing them too hard."

Russo talked about blood lactate - but what is it and why is it important to test?

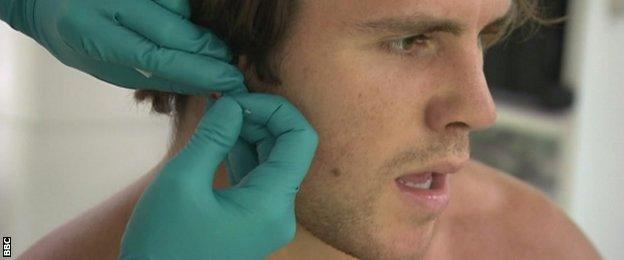

Dan Holman having his blood lactate sample taken from his ear

"During exercise, lactic acid is broken down into lactate and a hydrogen ion," explained Chris McManus from the University of Essex. "It is this lactate that accumulates in the blood and is reflective of the intensity of the exercise bring completed.

"Well-trained athletes are able to maintain a lower level of lactate accumulation during exercise at higher intensities."

If pain is your thing, you can have a go at it yourself. Start the treadmill at about nine kilometres per hour and increase it every three minutes, with a 45-second break in between.

You also need someone to take a blood sample during that short haven when you can suck in some oxygen.

For the footballers and I, however: "We start at 11 kmh, and they typically last up to 18-19 kmh," said McManus.

"We could all probably jump on the treadmill and run at 20 kmh for a couple of minutes, but these guys are starting at 11 and every three minutes it goes up by around 1.5 kmh."

Sounds great, doesn't it? So great that it was the only thing that the players - and therefore myself - were allowed to do that day.

My test

In preparation, I had probably consumed my entire bodyweight in water before my mid-afternoon test to avoid dehydration, so it was of some relief to me that after a long drive I was asked to provide a urine sample almost as I walked through the door.

Later, I watched on as some of the players were put through their paces - in particular Dan Holman, a man just eight months my senior, so a good comparison to see how I matched up.

My apprehension, though, was not helped by the fact that these players, at the peak of physical fitness, came off the treadmill totally out of breath and uncontrollably dripping with sweat.

"Difficult - I don't even know if that's the right word," said right-back Richard Brindley after finishing his test.

"The only real way to get through a run like that is to think about the rewards. This is what pre-season is all about."

Then it was my turn. I couldn't help but think that behind the kind, encouraging front the researchers were putting on, they believed this was going to end badly for me.

Feeling confident, running smoothly - it started so well...

I did a three-minute running warm-up at a speed which general members of the public start the test, before being thrown into it at 11 kmh.

I was laughing and joking with those around me. However, slowly but surely, the jokes stopped as my legs began to feel the burn. Not even a fan blowing tepid air into my face could cool me down.

My demeanour and running style changed drastically - from an upright, composed starting position to hunched over, with sweat-drenched hair flopping about all over the place. I was not a pretty sight.

Eventually, after 16 minutes 30 seconds, I could feel something turning in my stomach and stopped immediately, with my researcher Kelly needing to hold out her hand to stop me falling off.

Everything hurt. There is no other way to describe it.

I couldn't physically stand straight, I felt dizzy and I needed to lie down on the floor with my legs on a chair.

Exhausted at the end of my test, I was told this would help me recover quicker

As great and as helpful as my cameraman John was, having his lens in my face afterwards asking me to say a few words about how I felt was a challenge. Thankfully I had no energy to moan about it.

Slowly my body began to recover enough to get into the shower. I was the last person to do the test and it was getting quite late, but the researchers said they needed to stay for me to finish in case I collapsed, because "it happens sometimes".

Thankfully nothing did happen, and I went to the local supermarket and demolished a whole tiger loaf and some cocktail sausages before my drive home.

Results

A few days later, it was time to find out my results, and how I compared to striker Holman.

Firstly, they were looking at my anaerobic threshold (AT), where the change in lactate increases sharply.

A typical footballer's AT may occur at about 15-16 kmh, whereas mine had already surpassed AT at the initial starting intensity of 11.5 kmh. It wasn't looking great for me from the start.

Moreover, my starting heart-rate was 84% of my expected maximum of 196 beats per minute, whereas Holman's was 75%.

By the end of the test, my heart-rate had surpassed 200 beats per minute just before I pulled out.

And the final main point was that the footballer was able to run for an additional four minutes longer in the test and therefore achieve a peak running velocity of greater than 18 kmh. My peak running velocity was 16 kmh.

Now I'm quite proud of that, but when you think of the speeds we were going, he travelled much further than I did and I look much, much worse than he did when he finished.

But, to be honest, I was just happy to get through it at all.

- Published8 July 2015

- Published7 July 2015

- Published7 July 2015

- Published7 June 2019