Football talent spotting: Are clubs getting it wrong with kids?

- Published

- comments

Jamie Vardy has flourished at Leicester after being let go by Sheffield Wednesday at 16

Scouting football players as young as five, persuading an 11-year-old to sign a contract with private school education or offering a teenager's parents a house.

These are some of the things English clubs are doing to secure the country's best youngsters in an increasingly desperate fight to beat rivals to sign potential stars.

"Money talks," sighs Sheffield United's chief academy scout Luke Fedorenko as he describes how he has just lost two 11-year-olds to Manchester City. "But we must be doing something right."

Fedorenko was one of 320 coaches and scouts at a recent Football Association conference at St George's Park to discuss what one keynote speaker, Professor Ross Tucker, calls a "race to the bottom".

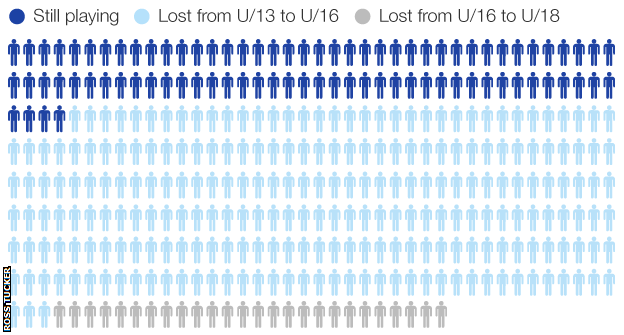

There are 12,500 players in the English academy system, but only 0.5% of under-nines at top clubs are likely to make it to the first team. There are also suggestions that drop-out rate in football is similar to other sports, such as rugby union, which can lose 76% of players between the ages of 13 and 16.

So are clubs still searching for the right formula for spotting talent? And with the number of foreign players in English football already making it harder for academy players to reach the top, is a different approach required at the bottom end to ensure talent doesn't slip through the net?

The crystal ball approach

Tucker says football should guard against studies in rugby union, where 76% of players can drop out between under-13 and under-16

"Anyone who tells you they can spot a professional player at five years old is basically lying," says talent ID manager Nick Levett, an expert in the eight to 11-year-old age group and one of several FA appointments encouraging clubs to improve in this field.

That extends to players aged 12, 13 or even later if Leicester striker Jamie Vardy is anything to go by. After being released by Sheffield Wednesday aged 16 for being too small, he was then sold by Fleetwood to the Foxes in 2012 and recently set a new Premier League record for goals scored in consecutive games.

Vardy's story, however, underlines an important factor: he stayed in the system, at non-league sides Stocksbridge Park Steels and Fleetwood, which allowed his talent to flourish at a later stage.

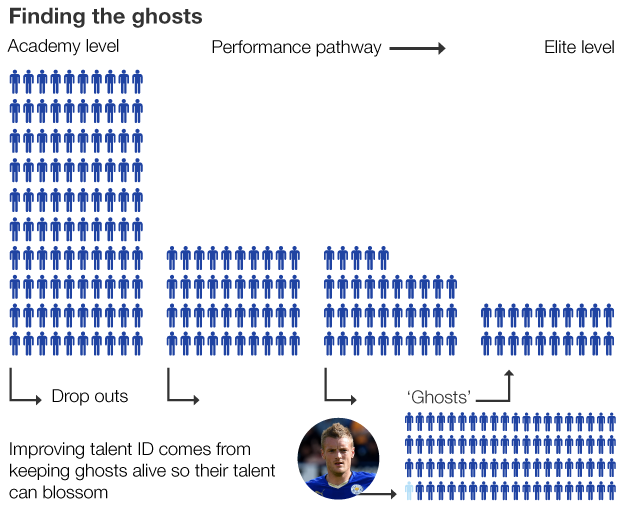

Tucker calls players like Vardy "ghosts"; those who once had potential but have been lost in the system. He says the key to improvement in identifying talent in youngsters is patience and recognising the bias which cuts players like Vardy adrift in the first place.

Bigger might not be better

Jaydon (left) and Joe (right) are both pictured aged 13 and were born 25 days apart

One of the biggest disparities in football or any junior sport is the relative age effect - the advantage of being born earlier in the school year, and therefore being more physically mature.

A seven-year-old born in September is likely to be bigger, faster and stronger than one born the following July.

Two seasons ago, Levett studied a Surrey junior league with 8,000 players and found that division one in all age groups had the oldest players on average, while division seven had the youngest. He also found that 45% of players in top-level academies have players born between September and November.

But among 57 England players with 50 or more caps, he found that the highest percentage of them - 46% - were born between March and May. It is a story replicated in other sports, such cricket and rugby union.

"The big drop-out in grassroots sport between the ages of 13 and 15 is the 'quarter three' or 'quarter four' kids," he says, referring to those born between March and August. "But somewhere along the line, the late ones are coming through."

So what's going on?

Levett believes that while the bigger players use their pace and power to solve problems on a pitch, the younger ones have to think smarter.

"The system has to challenge the big lads with the same sort of learning the small ones get every week," he adds.

Kids need to be kids

Nathaniel Chalobah played his first game at nine and played for England at 16

One of the reasons why the 10,000-hour theory has become so popular is that it gives rise to the notion that anyone can become world class if they put the graft in.

The theory suggests that practising any skill for 10,000 hours is sufficient to make you an expert.

"Parents are now taking their kids to five different clubs each week night in the belief that if they do more football they are going to get better," says Levett. "But it doesn't always work like that."

Levett claims Nathaniel Chalobah did not play his first game of football until he was nine, yet the Chelsea midfielder, on loan at Napoli, was playing for England Under-16s seven years later and is now a regular in the under-21 team.

Another survey carried out by Levett on under-21 players revealed that most of them did not start taking football seriously until they were 14 or 15.

Former Bolton captain Kevin Davies, whose son is in the Championship club's academy, recalls watching a match where he had seen under-10 players "reduced to tears" by the pressure.

"Kids need to be kids," he says. "If they are good enough and have the right attitude, they will get there in the end."

Any coach will tell you that practice is a good thing, but specialising in one sport can lead to boredom, psychological damage or injury.

Is 'edge' a good thing?

Luis Suarez, Alexis Sanchez, Sergio Aguero and Diego Costa all hail from South America

In praising Vardy's rise to prominence, Bolton boss Neil Lennon has said the current academy system produces "cocooned" players who perhaps do not have the edge to make it to the top.

Former Arsenal scout Damien Comolli says the problem is a Europe-wide one, with high wages among teenagers also denting their hunger.

"Most have a comfortable life and environment and those two things fail to produce players who need to fight every day on the field," the former director of football at Tottenham and Liverpool told BBC Sport.

"If you look at attacking players at the top 20 or 30 teams across Europe, many are from South America. From a mental aspect, they have a greater drive."

The Frenchman thinks players with an edge can be labelled as having "baggage" and are sometimes dismissed too early.

He asks: "Maybe we should look for an edge? What's the risk in taking them into an academy anyway. You're not giving them a 10-year contract are you?"

Unconscious bias

When Comolli first saw Netherlands striker Robin van Persie at Feyenoord, he was playing in the reserves and got sent off after fighting an opponent. Yet the talent was evident and he had a desire to improve, so they eventually took him to Arsenal.

But Levett believes many scouts are guilty of applying an unconscious bias, especially when watching players they might not automatically relate to.

He describes how a "very professional" scout with "high morals" once saw a talented forward start arguments with an opponent and the referee, before having a fight with a team-mate.

"There was a flash of genius when the player hit the post but the scout decided the player wasn't for him," Levett adds. "Soon afterwards, he had to explain to his club how they had missed out on Stan Collymore [former Liverpool and England striker]."

England Under-21 boss Gareth Southgate told BBC Sport: "What I'm more aware of over time is the individuality of people and how you have to treat them differently. You need to be careful of the assumptions you make."

Tucker says that up to 96% of players can drop out of sport before elite level, but the big gains come from keeping 'ghosts' like Vardy alive

Spotting the long-term learners

With the FA now helping clubs improve their approach to talent identification and the likes of Southampton running the world's first biological age tournament,, external there are some signs that the penny is starting to drop.

FA head of talent ID Richard Allen, formerly at Tottenham, says: "In terms of the players we have in academies, we are probably the strongest we have ever been but we can improve the way we look for 'ghosts'.

"Players who hit the heights have different pathways. We have to recognise that, rather than thinking at 16 it's too late for our boys to develop, so let's go abroad and buy somebody."

Levett warned that performance is not the only indicator: "There are many factors, but ultimately, we need to be patient with kids and spot the long-term learners. That's where the big gains are."

- Attribution

- Published4 December 2015

- Published10 November 2015

- Published10 October 2013

- Published7 June 2019

- Published20 June 2016

- Published2 November 2018