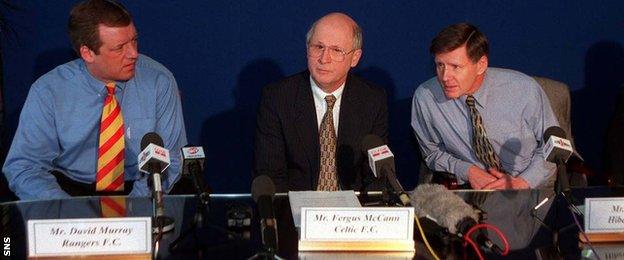

Fergus McCann: Man of logic, reluctant saviour of Celtic

- Published

Celtic Park was rebuilt during Fergus McCann's time in charge

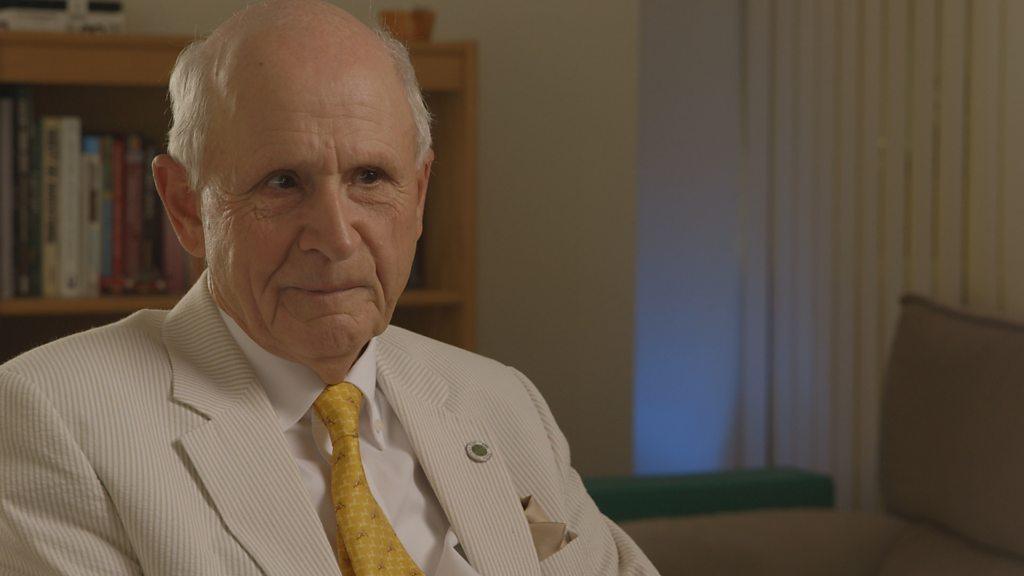

Fergus McCann never did think much of acclaim. He rescued Celtic but refused to consider himself as a savour.

"I'm just one of yesterday's features," says the Scottish-born Canadian businessman who had a controlling stake in the club for five years from 1994. "I'm a blip in the background."

While recalling his five years at Celtic Park, he doesn't veer off into sentimentality. His attachment to the club is entirely emotional - he tells a story of sitting at the back of a meeting while working for Marconi in Canada in 1967 listening to the European Cup final on the BBC World Service - but McCann's involvement with the club was "logical".

He is proud of the way the club is run now, not because of the league titles being accumulated but the clear business sense that prevails.

"It's so easy for the club to be criticised, as they so often are," he says. "You can buy short-term success at great cost.

Fergus McCann and Tom Boyd unfurled the championship flag in 1998

"You go back to the previous coach [Martin O'Neill], who brought in three players at £6m a pop, aged 28.

"They did well, they got to [the Uefa Cup final in] Seville, fine. But look at the balance sheet - the players are gone, the salaries are way up, we didn't make any money."

The assessment is typical of McCann: hard-headed, rational.

Act 1: Rescue

McCann spent two years talking to the Celtic board about trying to help the club as it struggled financially in the early 1990s. The response was generally "when will you be returning to Montreal, Mr McCann?".

So he regrouped, found some willing allies and set about trying to oust some of the board members and instigate "radical change". With Celtic only hours from bankruptcy and fans campaigning against the board, he made his move, flying to Scotland to pay off the club's debts and begin the process of taking over.

"I didn't have a plan to come to Celtic Park and run the club for five years," he says. "But it ended up being the formula that had to be applied to make it work.

Former Celtic chief executive Fergus McCann remembers the dramatic events of 1994

"Staying out of bankruptcy was expensive. That would have been the easiest way, as you have seen in the case of the other club in Glasgow [Rangers].

"I was doing what I thought was logical. I was not donating money - I was investing and I expected to get my money back. I didn't expect to make a lot of money. I did, but that's the way it happened.

"But it was not coming in as a saviour. I had a responsibility to the supporters to make sure their money wasn't wasted.

"I put two thirds of my money [he spent £9.5m] into the club. It was the correct thing to do."

Act 2: Building foundations

McCann never courted publicity or popularity. He surrounded himself with smart executives, directors and advisors, and spent five years trying to balance the club's ambition with the reality of its situation and financial imperatives.

He oversaw the rebuilding of Celtic Park, funded in part by a share issue, but also the strengthening of the club's foundations so that a similar period of turmoil could never happen again. There were obstacles along the way, though, as he found as he sought a successor to the manager, Lou Macari.

"I was under a lot of pressure to get Tommy Burns in, from board members and others I listened to," McCann says. "I suppose, looking back, maybe I should just have held firm and got the Dutch coach we were looking at at the time.

"I hired Tommy Burns, not because he was the best qualified candidate but because the fans would give him time. That was the asset he had.

Tommy Burns was not Fergus McCann's preferred choice as manager

"When I came in and Tommy Burns applies for the job, I go to meet him. But I got fined [£100,000] for the approach. The previous highest fine for a similar situation was £5k.

"Tommy Burns' salary with one year to go at Kilmarnock was £40k. I felt [the fine] was vindictive and unnecessary and excessive.

"[Celtic] are not entirely surrounded by friends. The Scottish environment is such that there has been some prejudice against immigrants.

"Celtic is seen as having a big Catholic population among its support. Celtic supporters understand that Celtic is a symbol of their dealing with that by not being second to anyone."

Act 3: Moving on

McCann sold up in 1999, making a healthy profit. He returned to Canada and a life away from the public eye.

He was booed by some Celtic fans when he unfurled the league title flag that summer but has since returned to glorious acclaim from supporters who have a different perspective now on his application of sound business principles ahead of rampant ambition.

McCann continues to follow Celtic, to understand their place in the game but also to hold views that would radicalise, and enrage, parts of Scottish football.

"All the small clubs hate Celtic and Rangers, who basically feed them," he says. "It comes down to human nature, but it also speaks to the structure in Scottish football.

Fergus McCann believes Scotland's other clubs dislike Celtic and Rangers

"A lot of things have changed in 30 years: television habits, media, salaries, worldwide brands, Champions League, all these new things. In Scotland, not much has changed.

"They fiddle around with deck chairs, but you have still got 42 supposed-to-be-professional clubs in a population of five million.

"There are five million people in Greater Manchester, who have only got two clubs. There are five million in Boston, who only have one club.

"Don't forget your dwindling potential audience. I watched a game, Celtic against Kilmarnock, 6,000 people, with close to 5,000 Celtic fans. What are Kilmarnock bringing to the game?

"They should maybe talk about British football. Celtic can take its place in British football. That's maybe where they belong."

Listen to the full interview on BBC Radio Scotland's Sunday Sportsound from 12:05 BST.

- Published27 August 2016

- Published27 August 2016

- Published23 August 2016

- Published14 January 2018

- Published7 June 2019