Scotland's Game: turmoil, hatred, chaos - the business of football

- Published

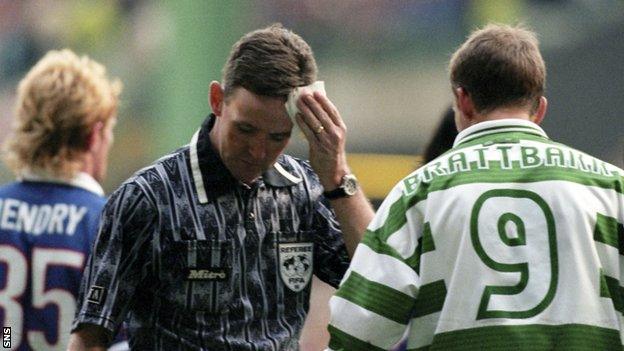

Referee Hugh Dallas was hit on the head by a coin in an Old Firm match in 1999

Episode two of Scotland's Game is called 'The Perfect Storm' and it's an hour detailing turmoil, hatred, hubris and collapse - an examination of the one area where Scottish football is in a world of its own: chaos.

We see Hugh Dallas' bloodied face during the title decider in May 1999. We see the targeting of Neil Lennon; bullets and bombs in the post, physical assault on the streets and an attack on the touchline while managing Celtic at Tynecastle - "a campaign of terror" as the journalist Kevin McKenna puts it.

It was deeply disturbing back then and, if anything, it's even more shocking now. The passage of time has only increased the sense of outrage at what Lennon was subjected to.

Finance is a big issue in episode two - particularly television finance. The deal with BSkyB, the push for SPLTV, the bitterness when the Old Firm pulled the plug on it and the arrival, and later, the demise of Setanta and the horrible fallout.

Clubs that thought a bad day would never come suddenly realised the insanity of their spending on expensive imports. Motherwell went into administration. A young Roberto Martinez, then on the books at Fir Park, is interviewed as the club was folding around his ears. "It's a war between football and business," he says.

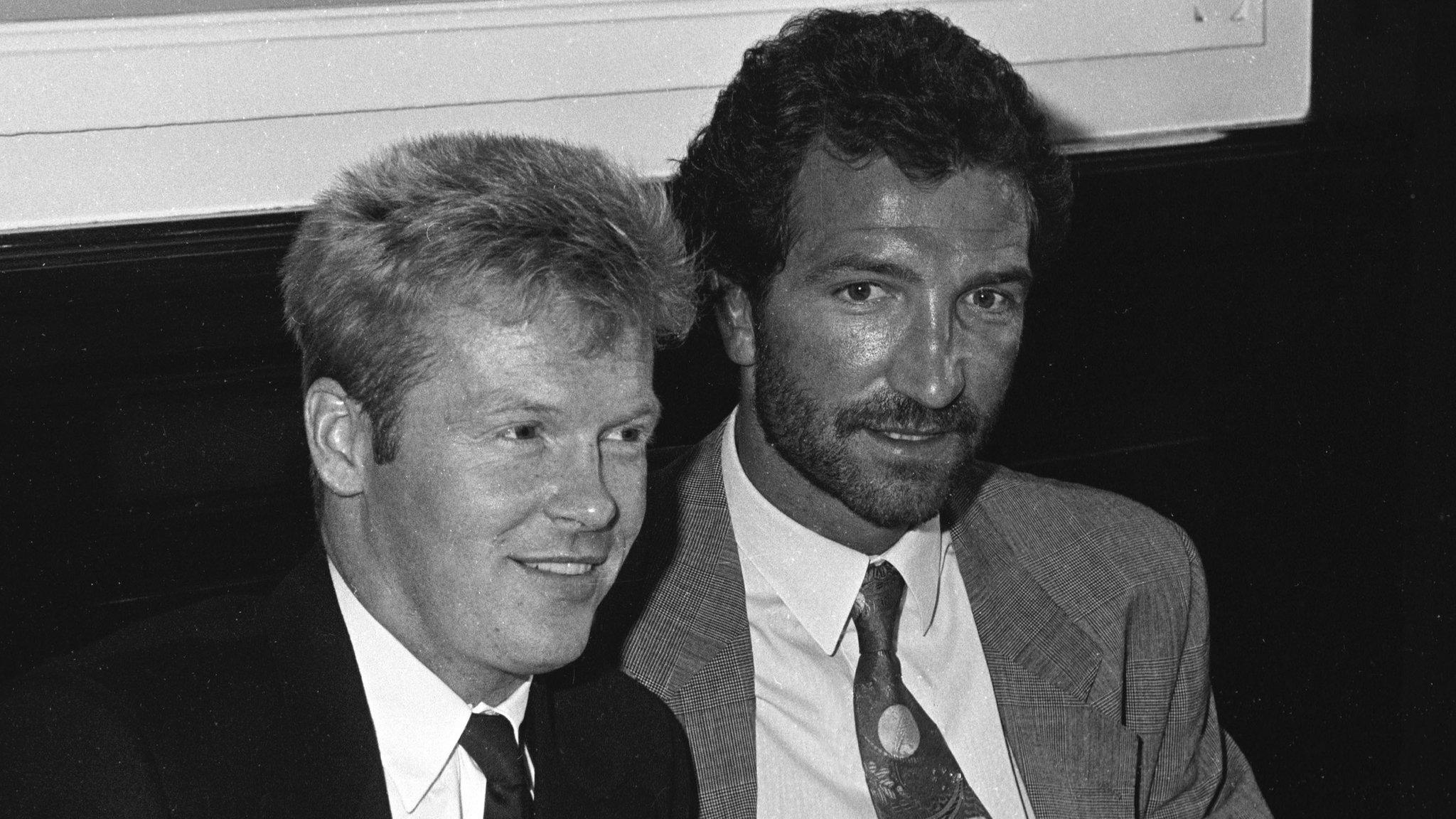

Roberto Martinez spent the 2001/02 season at Motherwell

If it was a war then it was a phony one. Football, as some clubs practiced it, was never going to win. Dundee, who had splurged on global names, also went into administration. Even what appeared to be real turned out to be a mirage.

The surreal rise and fall of Gretna was a morality tale for anybody who cared to listen - "an ego driven fantasy," says the broadcaster, Stuart Cosgrove. "It was an absolute Ponzi scheme. It was a con of the worst kind."

Scottish football has not lacked for false prophets. In the capital, one came from the east, Vladimir Romanov saving Tynecastle from the bulldozers but then, at the end of his reign, almost dynamiting the club's future.

Vladimir Romanov's methods at Hearts remembered

Romanov's bluster played well with the fans. Footage shows him promising to make Hearts champions of Europe in 10 years and vowing to build a new stadium "with the best atmosphere in the world."

Steven Pressley was captain of Hearts in that era and, along with Paul Hartley and Craig Gordon, one of the fabled Riccarton Three who called a press conference and memorably spoke of the "significant unrest" within the dressing room over Romanov's madcap meddling.

"At no time did Vladimir ever come and face me after I made that statement," says Pressley now. "I don't think he had the courage to face me."

When the administrators moved into Hearts they said it was about as grim as situation as they'd ever seen at a football club. The room they were sitting in when making the pronouncement had a leaky roof when the rain fell and a carpet that hadn't been washed in an age.

They had older supporters being held to ransom - donate money or else - and young fans turning up with their money boxes, anything to keep their club alive.

Paul Hartley, Steven Pressley and Craig Gordon exposed the extent of the unrest at Hearts in October 2006

Hearts have recovered. Through their Foundation and the stewardship of owner, Ann Budge, they are stable and looking forward. What has happened at Tynecastle over the past few years is one of the great stories of the past 30 years of Scottish football.

The fall of Rangers looms like the darkest cloud over episode two. There's footage of David Murray from 2001 dismissing those who were claiming that money was running out.

"Of course there's money available - this is Rangers football club," he says, before rounding on the critics who were saying otherwise.

"It makes great, sensational copy for you people who want to make it look as if we're in a crisis or something."

Murray had found a loophole in the tax system, giving him more disposable cash than the rest of Scottish football, allowing him to buy more players. Employee Benefit Trusts (EBTs) brought Rangers talent and trophies but they also brought a whole heap of trouble.

Alex Thomson, the Channel 4 investigative reporter who covered the EBT story, says: "What Rangers were doing was no more than part of that Wild West, out of control, global culture where tax avoidance, as opposed to tax evasion - which is of course illegal - is ingrained in everyone's culture; everybody is doing it, and if you're doing it better than the others, you gained commercial advantage.

"You wind up being a football club which is buying players - in its own words - they couldn't afford to gain, presumably and seemingly for sporting advantage, otherwise why would else would you do it? It gained a sporting advantage - they win 12 trophies in the first decade of the century - and lo and behold, no-one's paying tax."

Craig Whyte breezed into Glasgow in December 2010 for talks to buy Rangers from David Murray

From the archive, David Murray says he will only sell the club to somebody who has its best interests at heart. Against the advice of some of his board at Ibrox, he sold it to Craig Whyte, the only man who was prepared to buy it - for £1 - while the threat of a £50m EBT tax bill hung over its head.

Murray allowed Whyte in the door and the consequences were disastrous for the club. In a statement, Murray denies being responsible for the fall of Rangers. He puts the blame squarely at Whyte's door.

What happened then - and what happened next -will be talked about for the rest of time; Rangers in the Third Division working their way up. The seemingly endless array of characters flitting in and out of Ibrox. The fear and loathing.

For 30 years the Scottish game has convulsed violently. Year after year the things that we spoke about the most had nothing to do with football and everything to do with the business of football.

Maybe that's changing now. And if it is, it's long, long overdue.

Scotland's Game, a social history of football in this country over the last 30 years, continues on BBC One Scotland on Thursday at 21:00 BST.

- Published31 August 2016

- Published30 August 2016

- Published23 August 2016