England 3-0 Scotland: Scots should follow Irish examples to improve

- Published

Gordon Strachan's Scotland have won just two of their last eight competitive games

In a preamble that drew so much on nostalgia, there was another throwback, of sorts, in the dying minutes at Wembley on Friday night.

England, emboldened by their three-goal lead, knocked it about as if toying with the tired Scots. They passed and passed and passed and, all the while, the visitors chased and chased and chased. Forlornly.

The scene had an audible and visual backdrop. England supporters cried 'Ole!' and, in the air, they waved their white tee-shirts - a gift from the FA. Wembley basked in Scotland's hopelessness.

You wonder how many of the home crowd were around when Scotland lorded it in this place nearly 50 years ago, but there were echoes of that here.

There was nobody of Jim Baxter's class and no mocking keepy-uppy of that storied victory in 1967, but in those closing stages on Friday, the English message was the same as the Scottish one all those years ago - this is easy, oh so easy.

The Tartan Army could have closed their eyes to avoid it all, but there was no respite in the dark either.

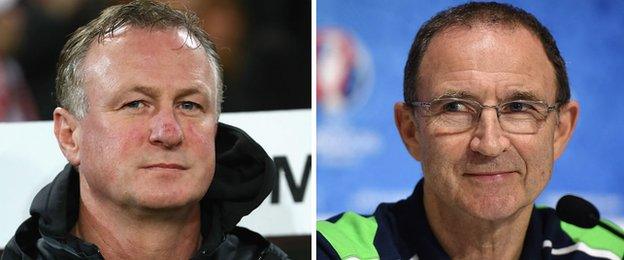

Michael and Martin O'Neill have an impressive record in charge of their sides

No matter what you do, there is no escaping the fact that Scotland are now fifth in their World Cup group. Fifth - despite being seeded third - and on life support in terms of a shot at qualification.

Gordon Strachan said that the game was cruel on his players - "really cruel" - but it wasn't. Footballing cruelty is borne out of an unlucky break or a refereeing blunder, not from your own inability to convert the chances you create and your own shortcomings in dealing with the chances created by others.

How could Grant Hanley's first-half header, which threatened the floodlights more than Joe Hart's goal, be deemed cruel? How could Leigh Griffiths' terrible error of judgement in shooting, instead of playing in Robert Snodgrass, be presented as a hard luck story? How could James Forrest's weak shot, early in the second half, be considered an example of the Gods being against the Scots?

Cruel was not the word. And this game wasn't even the place where the damage was done.

Everything would not look so thunderously awful today had Scotland not been so bad in their two previous games. Had there been three points against Lithuania and even one point against Slovakia, people could have taken a 3-0 defeat against England on the chin and not folded in a heap.

As it is, another campaign has all but gone and this is a natural end for Strachan now. He refused to talk about his own position in the aftermath of Wembley, but it is untenable and surely he knows it.

People will indulge in fatalism. 'We don't have the players.' 'Changing the manager will make no difference.' 'It goes much deeper than one man.'

Strachan not thinking about his future

Of course it does. It goes very deep. Scotland's demise as a nation - one which, for decades, produced a torrent of world-class players - is an epic story, a tale retold more often than The Mousetrap.

Have the debate (again) about the cause of all of this. Commission another blueprint. Get in the politicians and the sports management boffins if you like. Navel gaze to kingdom come.

Attempting to make things better in the future doesn't preclude you from trying to make things better in the present. Scotland needs a new manager.

Again the mantra goes that no man can conjure up a formidable set of centre-backs or the kind of predators in front of goal that were so absent on Friday. It's true, but the history of football is full of international managers who have inherited a failing squad and then hauled them forwards.

Strachan managed to do it himself for a short while. You don't have to look too far to find other examples.

Over in Dublin, Martin O'Neill inherited a Republic of Ireland squad that had, not long before, shipped nine goals in two qualifying games against Germany. They then dropped four points out of six against Scotland. O'Neill slowly turned things around.

The Republic went from losing 6-1 and 3-0 to Germany to beating them in what was the seminal moment of their Euro 2016 qualifying campaign. They then beat Italy at the Euro 2016 finals to make the knockout stage.

Scotland were beaten 3-0 by England at Wembley

It's too easy to say that the Republic's players are much better than Scotland's. Better? Yes. Is there a big gulf? No. Or, at least, there shouldn't be.

O'Neill's management has made them mentally strong, thoroughly organised and harder to break down. In terms of entertainment and class, they're no oil painting, but they're efficient.

The Irish team that beat Italy in France had defenders from Blackburn Rovers, Derby County and Burnley - all Championship clubs at the time. Behind their lone striker, they had a three-man unit drawn from Derby, Ipswich Town and Norwich City.

They had Shane Long up front. Long is a good player, but O'Neill's Ireland were hardly a team of all the talents.

Travel further north and you find a prime example of a manager making a difference. Before Michael O'Neill took over Northern Ireland, they were a soft touch and were utterly irrelevant and largely ignored in European football.

In the campaign before his appointment - Euro 2012 - Northern Ireland won just two of their 10 games. They drew 1-1 with the Faroes and lost 4-1 to Estonia. Things were grim.

The things you are hearing now about Scotland just not having the players is precisely what they were saying in Northern Ireland five years ago. No players, no prospect of players, no hope of any manager being able to alter that.

Scotland fans were left disappointed once more at Wembley

The squad that O'Neill took to the last 16 of the Euros last summer had just five players who were performing most weeks in the Premier League. He had four from the Scottish Premiership, one from Melbourne City and the rest from the English Championship and English League One. His three goalkeepers came from Hamilton Accies, St Johnstone and Notts County and had a combined age of 109.

On Friday night, as Scotland were losing at Wembley, Northern Ireland moved into second place in their own qualifying group following a 4-0 victory over Azerbaijan in Belfast. Azerbaijan had beaten Norway at home and had got a 0-0 away to the Czech Republic, but Northern Ireland put them away with the minimum of fuss.

In his starting line-up, O'Neill had players from Fleetwood Town, Millwall, Norwich, Blackburn, Charlton Athletic and Brighton. On the bench, he had two from St Johnstone and one each from Rangers, Aberdeen, Ross County, Sunderland, Wigan Athletic, Shrewsbury Town, Rochdale, Burton Albion and Kerala Blasters in India.

O'Neill, who lives in Edinburgh, has done a magnificent job. He has made a little go a long, long way. With his assistant, Scotsman Austin MacPhee, they are doing what Scotland are failing to do - and they're doing it with meagre playing resources compared to the ones at Strachan's disposal.

Forget Wembley. Would O'Neill's team have failed to beat Lithuania at home? Would they have surrendered so meekly against Slovakia away?

Northern Ireland have made the most of what they have - and there is a lesson in that for Scotland.

If the curtain comes down on Strachan's reign, then O'Neill would be a good starting point in the search for a new manager. Would he take it? The time is fast approaching when Stewart Regan needs to start asking that question for himself.

- Published12 November 2016

- Published11 November 2016

- Published11 November 2016