Uefa to launch study into link between playing football and dementia

- Published

One Premier League club will be involved in the study, which Uefa says will begin on Friday

Uefa has commissioned a research project that will examine the links between dementia and playing football.

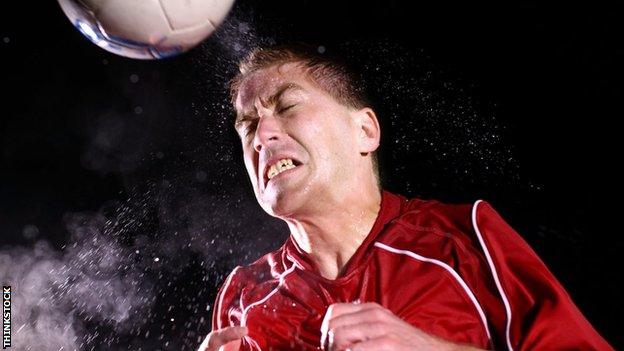

Tentative research published earlier this week suggested repeated headers during a player's career may be linked to long-term brain damage.

The research examined the brains of six players renowned for heading the ball - all of whom later developed dementia.

The Football Association has said it will look at the area more closely, but is yet to announce its own study.

European football's governing body Uefa says the project, which will begin on Friday, "aims to help establish the risk posed to young players during matches and training sessions".

One Premier League club will be involved in the study.

What is the FA doing?

The FA says it is committed to supporting research into degenerative brain disease among former players, but authorities in English football have been criticised over a perceived reluctance to confront the issue.

Speaking in April, the FA's medical chief Dr Ian Beasley said the organisation wanted Fifa to investigate.

He said it would be "taking some research questions to Fifa imminently" after it was revealed three members of England's 1966 World Cup squad - Martin Peters, Nobby Stiles and Ray Wilson - had Alzheimer's.

Ian St John, who played for Liverpool between 1961-71, says six of his teammates - from a group of about 16 players - now have Alzheimer's.

"I don't know why the FA and the PFA have covered this up for years," he said on the Victoria Derbyshire programme.

"I talked about it to the PFA a couple of years ago, and their answer was: 'Well, women get dementia, so therefore it's not an industrial injury'. Which is a load of nonsense isn't it?"

Former England and West Brom striker Jeff Astle, died aged 59 suffering from early onset dementia. The inquest into his death in 2002 found that repeatedly heading heavy leather footballs had contributed to trauma to his brain.

Speaking to BBC Radio 5 live, his daughter Dawn Astle said: "At the coroner's inquest, football tried to sweep his death under a carpet. They didn't want to know, they didn't want to think that football could be a killer and sadly, it is. It can be."

By the end he "didn't even know he'd ever been a footballer", she said, before adding: "Everything football ever gave him, football had taken away."

Chris Borland, top, is one of a number of NFL players who have retired early in recent seasons due to concerns over the effect of concussions. He quit the San Francisco 49ers at the age of 23

Following the NFL's lead

Uefa's project follows similar initiatives in other sports.

In September, American football's National Football League (NFL) announced it would spend $100m (£80m) on medical and engineering research to increase protection for players, after agreeing a $1bn (£800m) settlement to compensate ex-players who had suffered brain injuries.

That figure was agreed in April following a lawsuit by 5,000 former players who successfully claimed the NFL hid the dangers of repeated head trauma.

A UK RugbyHealth study is already examining the long-term health effects of playing rugby, including the effects of suffering frequent concussion.

That followed a World Rugby research project, which published findings of a potential link between frequent concussion and brain damage in 2015.

However, its lead researcher said it was "difficult" to draw robust conclusions, adding "further research was required".

What does the science say?

Researchers from University College London and Cardiff University examined the brains of five people who had been professional footballers and one who had been a committed amateur throughout his life.

They had played football for an average of 26 years and all six went on to develop dementia in their 60s.

While performing post mortem examinations, scientists found signs of brain injury - called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in four cases.

CTE has been linked to memory loss, depression and dementia and has been seen in other contact sports.

But the science is far from clear-cut. Each brain also showed signs of Alzheimer's disease and some had blood vessel changes that can also lead to dementia.

Researchers speculate that it was a combination of factors that contributed to dementia in these players, but they acknowledge their research cannot definitively prove a link and are calling for larger studies.

The Football Association welcomed the study and said research was particularly needed to find out whether degenerative brain disease is more common in ex-footballers.

Dr Charlotte Cowie, of the FA, added: "The FA is determined to support this research and is also committed to ensuring that any research process is independent, robust and thorough, so that when the results emerge, everyone in the game can be confident in its findings."

Analysis

BBC sports news correspondent Richard Conway

Many former players have been critical of a perceived reluctance by the FA and others to take action over a potential link between football and dementia.

Proving a definitive link is difficult but new research shows there may be a causal connection between heading a ball and brain illnesses in later life.

But is it just a matter for players of a previous generation, who used heavy leather footballs? Or does the problem persist in the modern age?

Answers are needed. It is already too late for those suffering, potentially as a result of playing the game.

It may, however, help many worried about whether they will be afflicted as they get older.

- Attribution

- Published15 February 2017

- Attribution

- Published15 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017