Man Utd: When watching the European Cup final meant risking a school beating

- Published

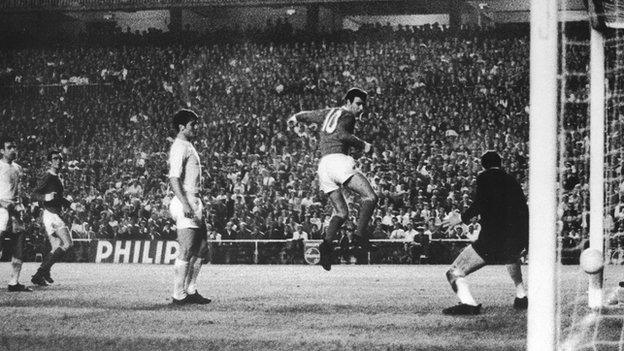

Manchester United captain Bobby Charlton exchanges pennants with the Benfica captain, Mario Coluna

Young Manchester United fans found themselves with a dilemma on 29 May, 1968 - skip school to watch their team become England's first European champions, knowing only too well the repercussions that awaited: the teacher's cane.

These were the days before corporal punishment was outlawed, external in British schools, and the threat was real.

Yet according to United fan Pete Molyneux, it was no choice at all on that night 50 years ago. He was prepared to risk sore body parts and more to be at the European Cup final against Benfica.

After three semi-final failures, the clamour to go to the big game, hosted at the old Wembley Stadium, was enormous for United supporters.

And Molyneux, 13 at the time, was fortunate to be in the near-100,000 crowd with his dad Bill.

"The Head Teachers Association said children going would be treated as truancy if you didn't bring your ticket into school as proof and get formal permission to go," said Molyneux.

"There were lads at school who went to the game without doing that and got the cane the next day. It sounds draconian but things were different back then.

"It started with a story about some schools turning a blind eye to absentees on the day compared with schools that were taking a hard-line stance and threatening to treat the matter as truancy."

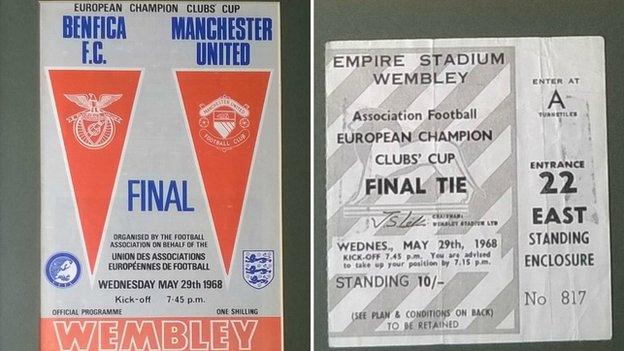

Pete Molyneux has retained his ticket and match programme from the 1968 European Cup final

Molyneux, who began following United in 1963, was initially told that going to the match was forbidden.

"The whole nation had a view," he said. "Bombardiers were writing letters to the Times saying it was an example of the country going downhill.

"In my hierarchy of needs watching United was more important than sitting through a maths or history lesson."

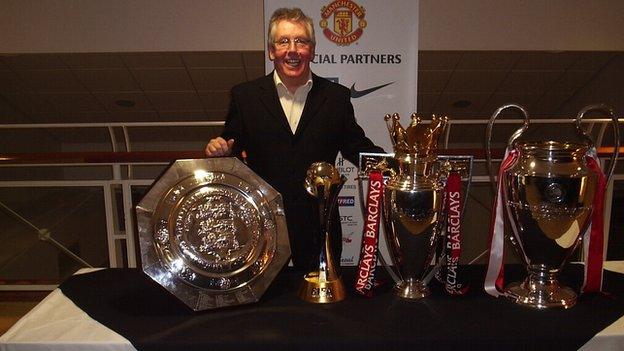

Pete Molyneux started going to games at Manchester United in 1963, when he was eight

Everyone wanted United to win

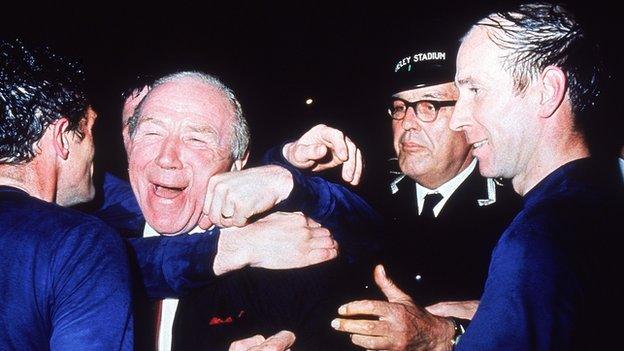

United's triumph was of personal significance to the club's manager Sir Matt Busby. Their 4-1 extra-time victory over Benfica came 10 years after the Munich air disaster, which killed 23 people, including eight United players.

"We travelled down by coach from Whitefield, in Manchester, on a glorious day," Molyneux said.

"The journey took between six and seven hours but every service station we stopped at was filled with thousands of United supporters. People were hitch-hiking and getting lifts on milk lorries to get there.

"There was no animosity between supporters then. Non-United fans were lining the streets to show their support and cheering the United coach.

"When we got to the ground, I remember a big following of Maltese United supporters. The atmosphere was constant noise."

Manchester United reached European Cup semi-finals four times and the final once under Sir Matt Busby

'One of the best 20 minutes of my life'

Bobby Charlton's early second-half goal put United in front against the two-time champions, who were playing in their second final at Wembley in five years.

But Jaime Graca, one of six players in the Benfica team to have played for Portugal in their World Cup semi-final defeat by England at the stadium two years earlier, equalised to take the game into extra time.

"You could see Sir Matt trying to get the players going for the extra half-an-hour because they all looked exhausted," said Molyneux.

Manchester United scored three goals in the first nine minutes of extra time to take the game away from Benfica and become the first English winners of the competition

However, George Best scored early in extra time - the first of three United goals in seven minutes.

"Once George scored, the floodgates were opened. I spent 20 minutes singing and celebrating. It was one of the best 20 minutes of my life," Molyneux told BBC Radio Manchester's Bill Rice.

"I can remember a huge spotlight shining on the players as they went up to get the trophy and then paraded it around the pitch.

"Some of the older guys had tears in their eyes and there was a feeling of having fulfilled a dream started by the Busby Babes in 1956."

Bobby Charlton scored twice against Benfica to repeat his two-goal World Cup semi-final contribution for England against Portugal two years earlier

'A wall of noise'

United's flirtation with the European Cup had begun 11 years, eight months and 17 days earlier - a journey that had been filled with trials, tragedy, effort and frustration.

Their victory also came in front of an estimated 250 million TV viewers - the biggest television audience since the World Cup final two years previously.

It vindicated the decision by Busby and the club's board to defy the Football League by entering the competition.

"Matt in particular would've seen it as a final OK with regard to the decisions that were made in the 1950s, particularly after what had happened," said David Sadler, who played in all nine of United's European games that season.

"Nobody patted them on the back and said that going to play in Europe was a great idea. In fact, it was the opposite.

"It was the old jaw-dropping thing, playing at Wembley - walking up that long tunnel, being hit by a wall of noise and thinking: 'This is how football is meant to be.'

"We played at Old Trafford, which was as good a stadium as anything about, but Wembley was bigger. The size of it took your breath away.

"Everyone looked at the pitch and thought 'wow', because in those days, pitches were just brown rectangles with a bit of green in the corner after September."

Route to the final

United travelled more than 14,000 miles as they played through four rounds to reach the 1968 final. There was a trip to face Maltese side Hibernians, another to Sarajevo, and a journey behind the Iron Curtain to face much-vaunted Polish champions Gornik Zabrze in a blizzard.

Yet arguably the toughest trip abroad that season was also the shortest, against a Real Madrid side who had won the competition six times.

Defending a slender one-goal lead from the first leg in Manchester, Busby's hopes of a first final at their fourth attempt hung by a thread.

"A lot of the lads went to church on the morning of that match," said Paddy Crerand, a midfielder in that United side.

"I think a few thought: 'We'll just go in any case to see if he can do anything for us.' Sometimes prayer can help."

It did not help that, four days before the second leg, they had missed out to Manchester City for the old First Division title - having lost two of their final three league games.

"Losing the league was a heartbreaker," said Crerand. "We went and played at Tottenham in February and we were 1/6 to win the league but we blew it."

Pulverised during the first half at the Bernabeu, United trailed 3-1 on the night, and 3-2 on aggregate - although an outrageous own goal by Madrid midfielder Ignacio Zoco had given them hope.

David Sadler, who drew United level on aggregate against Real Madrid, earned four England caps during his career

Yet with hopes of the final slipping away, United manager Busby and his assistant Jimmy Murphy gave an inspirational team talk - as memories of the club's tragic European history drove the players on.

"You could feel it [Munich] at times, particularly at half-time in the semi-final when we were 3-1 down," said Crerand.

"The way that Matt spoke to us in the dressing room and Jimmy Murphy, who was so fervent - he was like somebody who had got in from off the Stretford End and been put in the dressing room.

"Matt wasn't very happy about our performance or the way we had played and he just said: 'If we get the next goal, we're going to win.'

"Don't forget you're playing Real Madrid in Madrid in the semi-final of the European Cup and you're 3-1 down. How many teams can get a result after that?"

Crerand's free-kick laid the platform for Sadler to score and level the tie on aggregate.

Then the wizardry of Best prevailed, with the Northern Ireland winger laying on the decisive goal for Bill Foulkes, the 36-year-old defender who had been a survivor of Munich.

"Out of nowhere and totally not commissioned, Bill Foulkes turns up and slots one in like he's Jimmy Greaves," said Sadler.

Overcome with emotion, Charlton lay flat out on the pitch at the end as United celebrated.

"There were different groups within the team," Sadler added. "The older group, like Bobby and Bill, were closer to the boss and people saw it in different ways.

"Someone like Bill must have been thinking: 'This is going to be the last chance I'm ever going to have at this.'"

'You had to take food with you when played away'

As United attempted to relax before the final, their preparation involved watching the Epsom Derby - won by Sir Ivor, ridden by Lester Piggott - on screens erected by the BBC for a special edition of Grandstand, hosted by David Coleman from the gardens of their Surrey hotel.

Benfica's approach was equally modest, conducting their final training sessions at the Harlow sports centre in Essex, a five-minute walk from their accommodation.

"I remember the waiting and anticipation," said former Benfica and Portugal winger Antonio Simoes.

"We came three or four days before the game because, unlike today, we did not have a private aeroplane or special seats or anything like that. You had to take food with you when you played away from home."

Unlike the modern-day game - where players meticulously undertake a series of drills and stretches 30 minutes before kick-off to warm up core muscle groups - the 1960s approach was also rather more basic, with players limited to conducting their own routines in the dressing room.

Simoes said: "Today you warm up, discuss tactics and can go out on the pitch to familiarise yourself with your surroundings. Back then there wasn't a warm-up. We had to sit down and we had a ball we played with a little bit, killing time."

George Best scored 32 goals for Manchester United in all competitions during the 1967-68 season

'Best was like Messi'

Of primary concern to Benfica's Brazilian coach Otto Gloria was how to stop United winger Best, who was on his way to being named as the European Footballer of the Year for 1968.

Best had earned the nickname 'El Beatle' after dismantling the Portuguese side in Lisbon two seasons earlier, scoring twice in a 5-1 win.

And he struck decisively at Wembley two minutes into extra time, with United's second goal breaking their opponents' resistance.

Simoes said: "Manchester United were a very strong team anyway with two or three fantastic players but when George gets mad and dribbles past two or three players in a small space and scores a goal, what are you going to do?

"There are things you cannot stop. Look at Lionel Messi today. You know what he is going to do and he still does it.

"Michael Jordan was the same in the NBA. Everyone knew what he was going to do with a basketball and he was able to do it for years.

"When they are on fire, people like Best, Messi and Jordan have the kind of talent you can't stop."

- Published5 February 2018