World Cup 2018: Russian city Samara, football and the space race

- Published

The city of Samara is incredible proud of its space race history

2018 Fifa World Cup quarter-final: Sweden v England |

|---|

Venue: Samara Arena, Samara Date: Saturday 7 July, 15:00 BST |

Coverage: Live on BBC One and online; full radio commentary on BBC Radio 5 live and text commentary and in-play clips online and on BBC Sport app |

Where the Sputnik stadium used to stand there is a housing block, Orbita's pitch is now wasteland and the old Voskhod ground, named after a space rocket, is crumbling into ruin.

These are just some of the old football arenas in Samara, the Russian World Cup host city that is most famous for helping drive the Soviet Union's space race with the United States.

About 1,000km south east of Moscow on the Volga river, Samara will host the quarter-final game between England and Sweden, its final match of the tournament.

The crumbling Voskhod ground which is covered in broken glass, weeds and grass

But way back when, Samara's factories built the rocket that in 1961 propelled Yuri Gagarin into orbit as the first man in space.

It is a city of about 1.2m people and is still home to Russia's aerospace and aviation industries. But since the collapse of Communism in 1991, the teams that used to represent its factories - and the places where they used to play - have been disappearing.

Take Voskhod. It means sunrise or dawn but was also the name of a series of rockets that launched the Zenit reconnaissance satellites that observed western powers during the Cold War.

And it was also the name given to Soviet space engineering company Motorostroitel's factory team. Motorostroitel is now part of a new bigger enterprise, JSC Kuznetsov. They still make rocket engines but they no longer play football.

Company headquarters on Zavodskaya Shosse (Factory Road) are about 200m from where Voskhod used to play.

Walking past a pile of dumped rubbish, an abandoned car and out onto long grass, you see it - one crumbling concrete stand, covered in broken glass, weeds and shrubs.

There are goalposts, a few kids kicking a ball around, others chasing each other on broken ground and a couple of guys drinking beer while they contemplate the enormous tower block rising opposite.

The old Voskhod ground, named after a space rocket, which is crumbling into ruin

A couple of metro stops away - on the way from the centre you pass stations called Sovetskaya, Sportivnaya, Gagarinskaya and Pobeda (victory) - I find the old Orbita stadium, round the back of a brand new leisure centre.

All that remains is the rough outline of a pitch and the concrete steps climbing up to where once there would have been an entrance. Now they lead you up onto a raised stretch of rubble and wilderness. A father is helping his two young children fly mechanical planes that racket through the sky, round in circles above two pairs of badly bent goalposts.

The old Orbita stadium which is round the back of a new leisure centre

This is only one side to the picture here of course - beneath the surface. If you look to Samara's northern outskirts, you will find a different story. Especially this month.

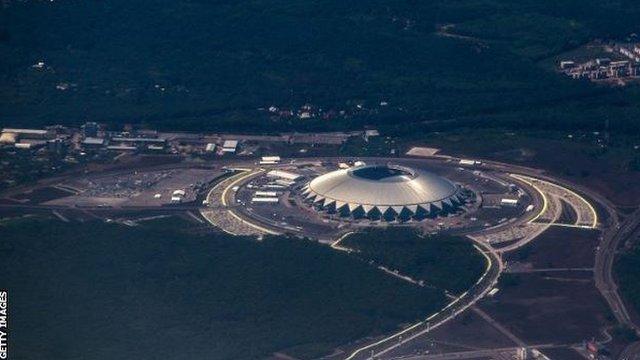

There is the brand new 45,000 Samara Arena, shaped like a stereotypical UFO.

Next season, the one professional team here - Kriylya Sovetov - will inherit the stadium on their return to the Russian top flight. The name means Wings of the Soviets.

They were formed during the Second World War by footballers who had been evacuated from Nazi-occupied western Russia, when many of the country's war factories were relocated here.

Kriylya Sovetov will inherit the 45,000 Samara Arena next season. The name means Wings of the Soviets

The capital itself was going to be moved if Moscow fell, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had a secret bunker built. The city's population grew by two hundred thousand as men, women and children arrived from the Donbass, Minsk, the Baltic states, and produced thousands of airplanes.

I wanted to know what kind of links Kriylya had with the aviation and space industries now. I tried the local football museum, which for some strange reason was closed, despite being just next to the bustling Fifa Fan Fest.

I eventually did track down one of the museum's two directors, Sergey Leibrad. I don't think I've met a man who has quite so much love for football. He and Alexei Chernyshev only established the museum in 2007 but they have gathered so many special items going back much further.

Sergey Leibrad at the football museum in Samara

Over the course of a brilliant and meandering, 45-minute monologue, Sergey entertains a small crowd gathered for a special Sunday tour.

Exhibits include letters from Lev Yashin, a signed photo from Louis van Gaal whose AZ Alkmaar visited in the Uefa Cup, Jan Koller's oversized running trainers, and an Andrei Kanchelskis signed shirt - the former Manchester United winger ended his career here.

There are also many photos of prolific former striker Boris Kazakov, who died in tragic circumstances at the age of 38, drowning in his car after it fell through a frozen river in 1978.

"Really there are almost no links now between the space factories and football teams, they have all gone since the collapse of Communism and the years of economic crisis. They are just no more, all the old stadiums have fallen into ruin," Sergey said.

"Of course it's a shame because football has a huge cultural value. Samara is a city of 1.2m people, and it has just one professional team."

Also at the football museum, I hear that only a few days ago another of the region's teams, third tier Syzran 2003, folded because it couldn't afford to play next season.

Kriylya almost went bust in 2010, when it was bailed out by the state. I'm told sardonically that "Vladimir Putin put one of his friends up to it". The club's owner now is technically the Samara regional government, and it is sponsored by a betting company.

The city of Samara used to have another name - until 1991 it was Kuybyshev, a place the Soviet Union kept closed to foreigners.

A team called Wings of the Soviets will play in the Samara Stadium

It is a place that still loves football despite its changing relationship with the game - Sergei Maryshko from the city's amateur football federation makes that point very strongly.

"There are about 180 amateur teams in the city, with more and more youth teams growing, and we expect that during the World Cup, where Russia is playing so well - that growth will continue into the future."

And it is true - everywhere you go football is all people are talking about at the moment. It's on the promenade along the wide river Volga, on its beach where locals relax in the thirty degree sun, at the markets where aubergines and watermelons are bundled out the boot of Ladas.

Interestingly, one of those 180 does include a Voskhod team, competing in the city's highest amateur division but with no relation to the former factory side. So where does the name come from then?

"They just liked it," Maryshko says.