Len Johnrose: 'I'm not afraid of dying' - ex-player on living with motor neurone disease

- Published

- comments

Former midfielder Len Johnrose opens up on BBC Radio Lancashire about being diagnosed with motor neurone disease.

There is no cure for motor neurone disease.

Half of those affected die within two years of being diagnosed with the rapidly progressing illness that can leave people locked in a deteriorating body, unable to move, talk and eventually breathe.

This week, Len Johnrose - a former midfielder who made more than 400 Football League appearances for Blackburn Rovers, Hartlepool, Bury, Burnley and Swansea City - went public for the first time about living with the illness.

Little over a decade since his playing career came to an end, the 48-year-old father-of-three, now a school teacher, admits he has already researched assisted dying as he fears the debilitating impact the illness will have.

Here, he tells BBC Radio Lancashire about the harsh reality of living with motor neurone disease.

'I'm not angry - who would I be angry at?'

I've never thought 'why me?' I've never particularly even questioned why it's happened. There are some days where I just think it's an absolute bag of you know what, but I'm not angry about it. Who would I be angry at?

It is one of those things. I could get run over by a bus one day... life can be very, very cruel. That's not just me, people's lives are whisked away from them without warning. But I'm not angry.

The biggest thing is mentally it's difficult. Some days are better than others, and I've had some really, really dark, down days. At the minute I'm just coming out of a really bad phase, post-holiday.

The last week has been absolutely horrendous, but I'm gradually getting out of it. You don't want to speak to anybody, you don't want to get out of bed, you have suicidal thoughts, it's absolutely horrendous.

I was always one of those where if it's light, I'm getting up. During the close season, if it was light I would go for a run, go to the gym. Now, I just don't want to get out of bed. Once I'm out of bed and showered, then I'm generally feeling better as the day progresses. But at 8 or 9pm I'm tired.

'Mentally I was OK, and then it hits you...'

I was diagnosed in March last year.

I initially went to the hospital about a fracture which hadn't healed. I thought there was a nerve problem, so they did some electrical tests. Whilst there I just asked them to have a look at my other hand, because I had felt a little bit of weakness there months prior.

The consultant dashed out of the room and brought someone else in. That put me on the back foot a little bit, and I was told I had to come in for some more tests.

I had an uneasy feeling about it, but you look on Google and all the stuff you shouldn't and after about a week I remember ringing up my wife and saying 'I know what they're looking for'.

I just laughed about it, I thought 'it isn't that. My legs are absolutely fine, it's not that'. She'd been worried all week because that was the first thing she thought about.

When we went for the second investigation we just asked them outright and said 'this is what we think it could be'.

It was probably August or September, another six months before I found out. During that six months things were progressing anyway, not at an alarming rate, and every minute of every day it was on my mind.

Motor neurone disease affects four parts: upper limbs, lower limbs, back and throat, which whenever you've got a sore throat you worry about, because it stops you swallowing.

When I was tested the first time they said there was an issue with my arms, then they did my legs and said there was something very slight in my legs. If you've got two areas affected they say you've possibly got it. If you've got three, you've definitely got it. When I went back, they said 'you're affected in three areas now', and that was that.

When we found out we both broke down, but it wasn't the world's biggest surprise. For the next week or so I couldn't have been more pragmatic. It was 'right, this is what we've got to do...' Mentally, I was OK, and then it hits you, really. And that's when it started to be a struggle.

'Not telling people felt like a guilty secret'

It was some months before we told the children. Things were becoming more obvious. The first thing it affected was my hands, upper limbs. So we'd be going out for family meals with people not knowing, and I'm struggling to cut things.

The children knew there was a problem. We got away with it, if you like, because I'd had issues with my back - unrelated, which I eventually had surgery on last November - so me not walking properly they put down to that.

But it was obvious with my hands. I remember my son saying to me 'dad, you only broke one hand, why are both hands an issue?' So they were aware something was wrong, and because of the time element, you don't know what you're going to be like from one day to the next, or one month to the next.

So, it was 'do we protect them? And how long do we protect them for?' We told them about Easter time I think, which was horrific, it really was. My son has really struggled with it since. My daughter seems to be keeping everything bottled in, seems to be coping really well, but I'm quite worried about her.

That was a bad week, because we ended up telling a lot of family then as well. It was quite a stressful week.

With the children it felt like a guilty secret. I've not done anything wrong, I didn't ask for it.

I speak to the neurological psychologist on a regular basis, you just need an outlet sometimes.

That outlet might not necessarily be the ones closest to you, because they're living it in their own world anyway and the last thing they want to do is hear it over and over again when they're trying to keep themselves and the family together.

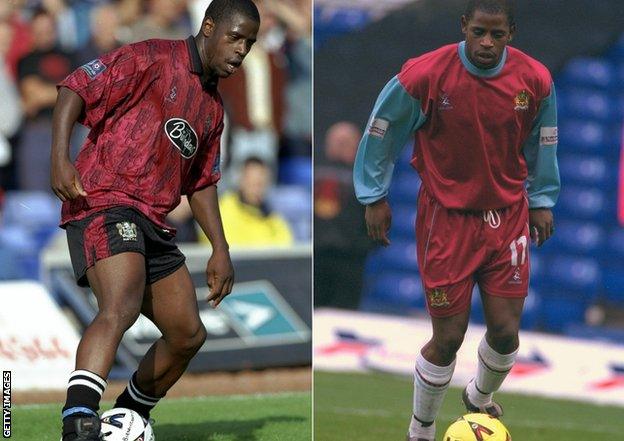

Johnrose was regarded as a tough-tackling midfielder throughout his 16-year professional career

'50% die within two years'

Planning for the next step was difficult.

The condition doesn't run linearly - I could be fine for a week, two weeks, whatever, and then suddenly you wake up one morning and can't move your finger.

There are certain organisations out there, there's an MND team in Preston who are really helpful, but it's so difficult to plan.

What they try to do is get you to make the life you've got now easier, get you to cope and make adaptations and regards planning - it's horrific to say, lifespan-wise, 50% die within two years. I think it's 90 or 95% die within five years.

You've not got a long-term goal, but there are examples of people that live beyond that - Stephen Hawking is one.

It is difficult to plan and you've got to get things in place - wills, funeral packages and that sort of stuff. A lot of the time I am quite pragmatic about it, but there are a lot of down days.

'I'm not drunk, I've got MND'

I've got three children, but two live at home. I spend a lot of time with them and they can see me struggling walking. People don't know about the disease - I've spoken to people at school and they've said 'oh, I don't really know about it', which is fine. That's not a criticism, but people don't know about it.

I've spoken to a friend about things that are starting to affect me and he said he didn't know about it, and we speak every other day. So people don't know about the harsh realities. This is not about getting sympathy or anything like that, it is something that needs more exposure for people to understand.

I walk around and I'm staggering. I thought to myself I'm going to get a t-shirt which says 'I'm not drunk, I've got MND'.

I remember going into a supermarket with my daughter a few months ago. Packing's hard and even lifting, you've just no strength in your muscles, so she was packing for me.

I got a bottle of wine and asked her to put it in, and there was a big kick-off about her putting it in the bag - I'm clearly not buying it for her, so there was a stand-off for about 20 minutes and they ended up apologising. It's things like that.

I have these straps, which give me a little bit of support. Some days you don't want to wear them, just to free your hands, but if you don't wear them then there is nothing there to trigger to anyone that there is an issue.

Most days, if I'm busy or talking - which I do a lot - I'm OK. It's mainly when there's a lot of time on your hands. When I was off for three months after the back surgery, that was a difficult time.

Having said that, it is progressing and it's starting to become a little bit difficult really.

Johnrose, seen here playing for Burnley, scored in a win for Swansea on the final day of the 2002-03 season that kept the Welsh side in the Football League

The fear of deteriorating

I said from day one of my clinical psychology meeting 'at X point, that's when I want to go'.

Now the parameters change as you get to X point, but I said 'when I've not been able to wipe my own backside, that's when I want to go'.

I'm not afraid of dying. The thought of hanging around, for want of a better phrase, in a wheelchair, not being able to communicate properly or do anything - your eyesight is great, your mind is still fine, but you actually can't do anything. No, put me down - and I couldn't be more serious about that.

I've already looked at it, going abroad, and I genuinely wouldn't want to hang around.

I've discussed it very briefly with my wife. It's not something she wants to talk about. It's not what you talk about at the table. I've certainly explored it. But that's no fun for me at all, it's not what I want to do.

Telling people about having motor neurone disease is not a case of trying to move on, it's just another step forward.

I eventually want to put it out there for people to know how I'm coping or not coping, which might mean something to people as well as trying to make some good out of it.

Typically, people will be older. In that aspect I'm still relatively young and, fitness-wise, I was very fit, so it's seeing if anyone else can relate to what I'm going through.

'A very devastating condition' - what is MND?

Chris James, from the Motor Neurone Disease Association, explains the illness: "Everybody's journey is different with MND, but Len's story is fairly typical. The common symptoms are people will lose the ability to walk, to perhaps talk, they lose the use of their arms and ultimately to breathe.

"It's a very devastating condition. There is no cure for MND. There is a lot of research going into finding a cure and indeed into finding treatment, which we are still struggling to find.

"However, there have been great advances over the past few years in research and there is some hope now we might be moving towards some treatments for the disease.

"Stephen Hawking is very unusual in terms of MND, he lived for a very long time. Half of people die within two years of diagnosis, and a third within a year. It can be a an extremely rapidly progressing condition."

A full interview with Len Johnrose will be broadcast on BBC Radio Lancashire on Wednesday, 22 August at 18:00 BST and will be available to listen again on the BBC iPlayer for the following 30 days.

If you are affected by the issues in this article, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line http://www.bbc.co.uk/actionline