With Premier League profits and EFL losses - is football paying enough tax?

- Published

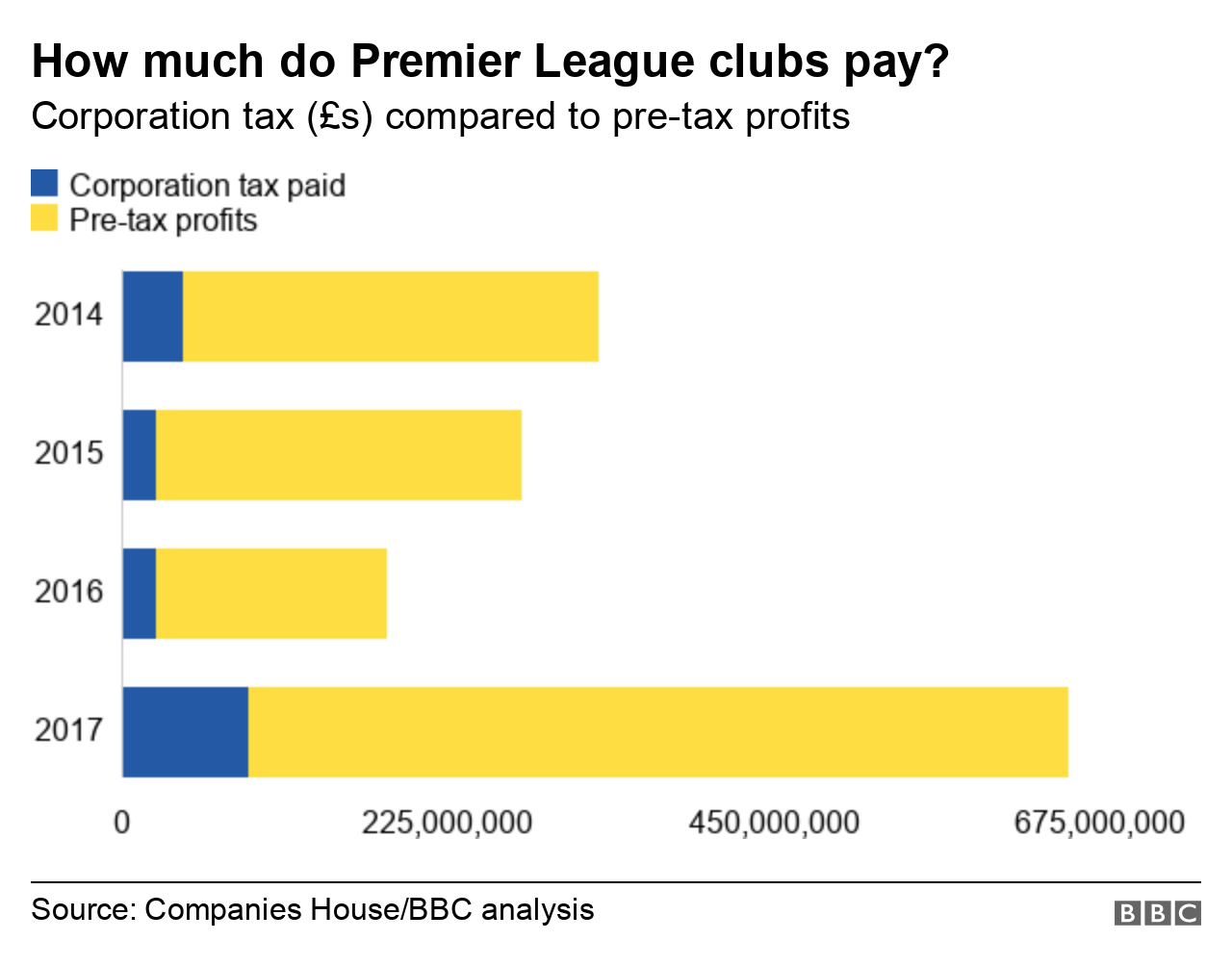

Profit-making Premier League clubs paid more than £177m in Corporation Tax from 2014-17

Football's relationship with the taxman has been back on the agenda over the last month, with Revenue and Customs issuing winding-up petitions to Bolton and Bury, and making enquires into a record number of footballers and agents, external for "tax risks… including image rights and agent fees".

But is there a wider issue in the sport? Do Premier League and English Football League (EFL) clubs pay enough Corporation Tax?

What is Corporation Tax?

If a company is based in the UK, it pays Corporation Tax, external on all of its profits from the UK and abroad.

Football clubs, like any other company, only pay Corporation Tax if they make a profit, although those profits can be set against historical losses which will reduce the amount paid.

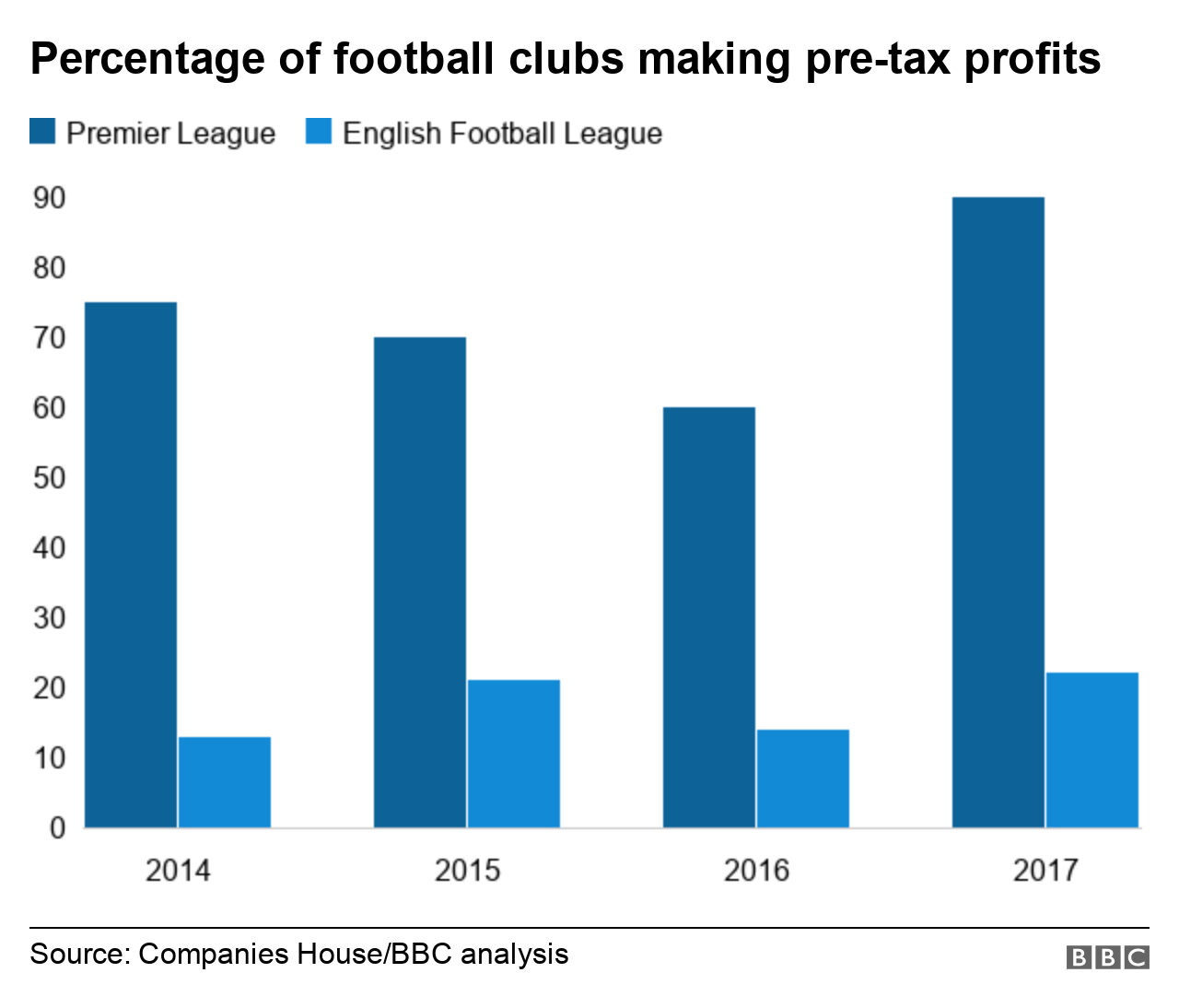

In the Premier League, 18 of the 20 clubs recorded a profit in 2016-17, compared to only six of the 24 sides in the Championship.

How much do Premier League clubs pay?

BBC England's data unit and BBC Sport analysed public accounts on the Companies House website - covering the four years until 2017 - and found:

Profit-making Premier League clubs collectively paid more than £177m in Corporation Tax from 2014-17

The combined turnover of profit-making Premier League clubs in the same time was more than £11bn

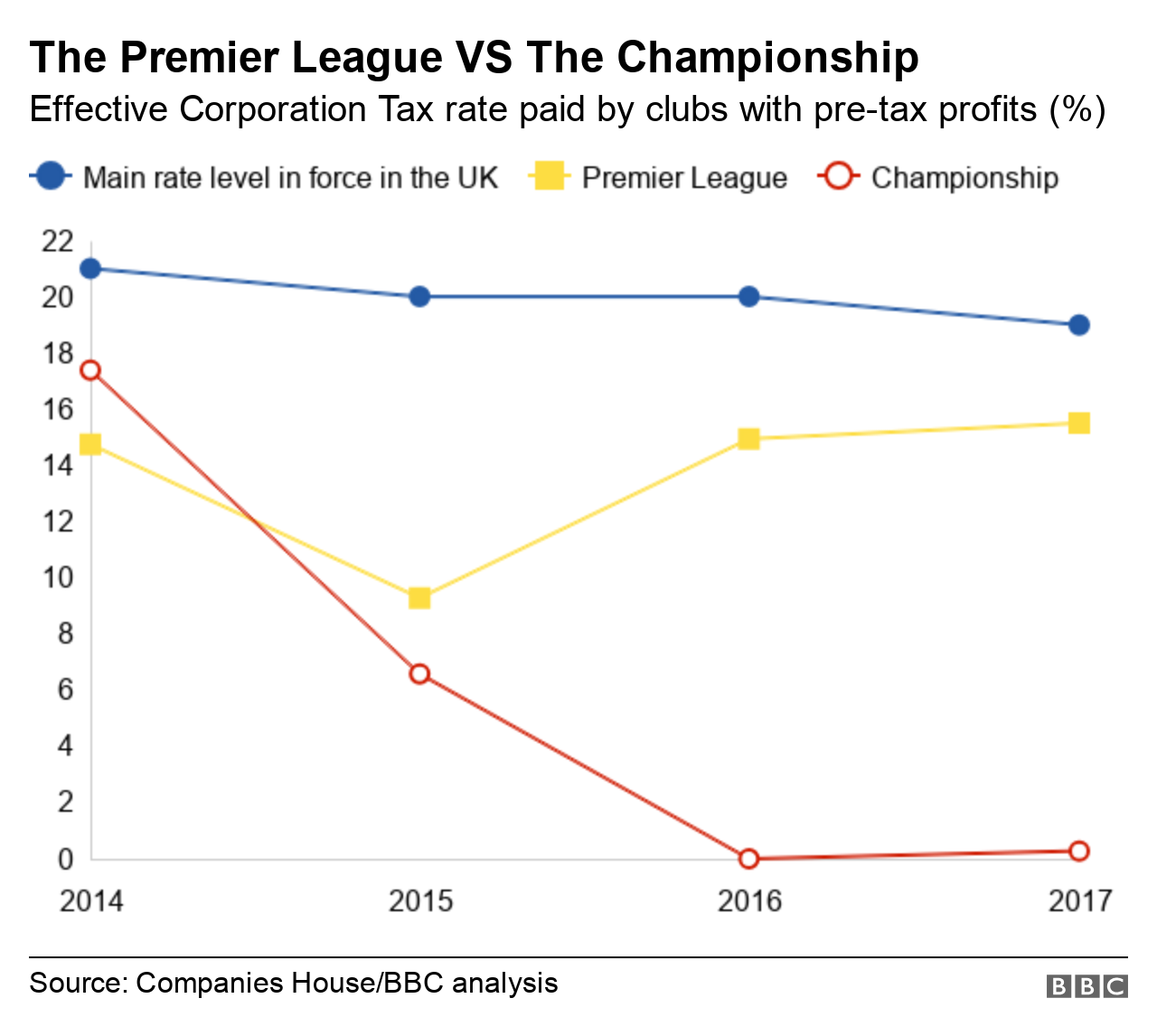

The amount Premier League clubs paid represented an effective payment rate ranging from 9%-15% over the four years, below the level in force across the UK of 19-21%

For comparison, the effective rate paid across all arts, entertainment and recreation businesses in 2016-17 was 10.5% of gross profits, according to government data, external

What about in the English Football League?

In both of the past two years, nearly two thirds of Championship clubs spent their entire turnover or more just on the costs of their staff, including players, coaches, management and administration

And there were fewer teams which made pre-tax profits in the three EFL divisions (72 teams in total) than did Premier League clubs in each of the past four years

Therefore EFL clubs which made pre-tax profits paid 0.04% as an effective Corporation Tax rate in the past two years, during which time they collectively turned over more than £275m

So is that an issue?

Campaigners say low tax payments hit the "poorest people" and stop governments being able to pay for public services.

Robert Palmer, from Tax Justice UK, a campaign group advocating progressive taxes as a component of "fair society", said: "Tax is a basic building block of our communities, paying for the roads, hospitals, and local football pitches that we use."

Chris Anderson, a professor of economics at the University of Warwick and former managing director of Coventry City, said the nature of running a football club meant it was "more complex" than concluding EFL clubs should pay more Corporation Tax because of their importance to other businesses and communities.

HMRC told the BBC it was currently making enquiries into 40 football clubs - nearly half of the number of clubs in the Premier League and EFL - for a range of issues, including image rights abuse and agents' fees.

It said it had recovered £355m of "extra tax" from professional football since 2015.

Why are clubs not paying more?

Corporation Tax is only paid on profits and clubs have used historic losses to absorb profits in later years. So, if a club hypothetically had losses of £3m up to 2016 and made a profit of £4m in 2017 it would only pay Corporation Tax on £1m.

Football finance lecturer Kieran Maguire said EFL clubs, especially those in the Championship, were paying less because they were "seduced" into paying high wages and transfers chasing potential riches from promotion, which led them into making losses.

Current spending limits for clubs - Profitability and Sustainability (PST) rules - allow Championship clubs to make up to a £39m loss over a rolling three-year period.

The spending limits had, however, also helped Premier League clubs sustain profitability over each broadcasting rights deal, Anderson said.

The Premier League said there were "wider benefits to its financial health" and it had "generated more than £3bn in tax for the Treasury in 2017 and clubs and their supply chains accounted for roughly 100,000 jobs".

What are the league rules?

In the Premier League, Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules in place from 2014-16 limited the increases clubs could make in spending on players between seasons that were funded purely by new broadcast revenue.

They could, however, spend more on players from their "own revenue", including commercial or sponsorship deals, profit from player sales, an increase in ticket sales, or Uefa prize money, such as from participating in the Champions League.

There was no cap on player costs or wages in the Championship but the rules limited losses to a maximum of £13m per season, or £5m per season if the owner did not inject cash into the club to cover those losses.

FFP has since been replaced with Profitability and Sustainability rules, which meant clubs that remained in the Championship were permitted to lose a total of £39m over a three-year rolling period.

This loss is not the same as the accounting losses published by clubs, as some costs - such as infrastructure, academy, community and women's football - are excluded.

Accountancy firm and football business analysts Deloitte said "most financially-aware observers would be unsurprised" by the BBC's analysis because the Premier League had only become profitable "relatively recently".

Deloitte's own figures suggested Premier League and EFL clubs had both, however, been paying an increasing sum of VAT on matchday income and other employment taxes such as National Insurance Contributions and PAYE on wages every year for the past decade.

Premier League players paid £1.1bn in tax during the 2016-17 season, an Ernst and Young report estimated., external

Should football clubs be treated differently?

Former Coventry managing director Anderson said clubs should be considered as more than a "normal business" because other companies and entrepreneurs, from newspapers to food and scarf sellers, and hotels, benefit from their existence.

"My main issue with this kind of analysis is that it treats clubs purely as businesses," he said. "But 'normal' businesses that can't find a way to become profitable will become extinct. Football clubs don't, which I see as evidence that they really are more than that.

"Government has no strong incentive to have these clubs go out of business. That's as it should be, if you ask me, as they contribute greatly and positively to the fabric of so many communities."

He added that the tax credits some clubs get "could be seen as rewarding historic failure", but admitted "I don't claim to know what the right answer is".

Do clubs have a wider responsibility?

Palmer, from Tax Justice UK, said paying tax was "at the heart of responsible corporate behaviour" and the sport's rules seemed "designed to allow clubs to run up loss after loss".

"League bosses should make sure that they're not encouraging financial behaviour that slashes tax bills, and politicians should tighten up the tax rules to make it harder for companies to do this," he said.

The Treasury said since April 2017 it had "restricted the use of historic losses" so the share of profits that could be relieved with past or historic losses was now 50%, above a £5m profit allowance for companies.

Anderson said: "Premier League clubs currently have no reason not to be profitable and pay tax; I'm not sure the same applies further down the pyramid.

"The fact that there is a steady rate of 15-20% of EFL clubs [over the four years of BBC analysis] that are profitable suggests that club owners are happy to sustain losses in pursuit of promotion. It also suggests, though, that it is entirely possible to be profitable.

"What continues to surprise me is that virtually everyone in football accepts as fact that spending money - in fact, losing money - is a pre-condition for success in football in the lower leagues.

"I think it's lazy thinking and a lack of imagination for how else it could work."

- Published23 October 2018

- Published18 October 2018

- Attribution

- Published4 December 2018