The two halves of the late Zaire striker Pierre Ndaye Mulamba's life

- Published

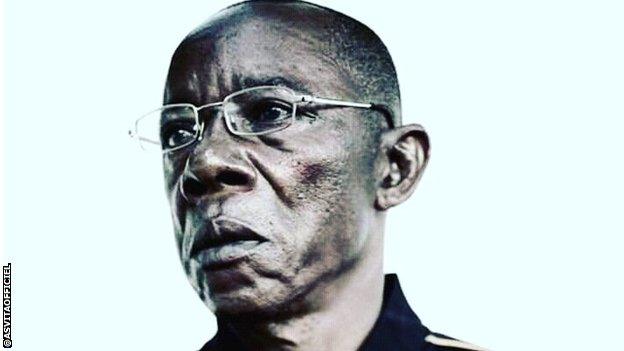

The late Pierre Ndaye Mulamba was the top scorer as he helped Zaire (now DR Congo) win the 1974 Africa Cup of Nations (Photo courtesy of @AsVitaOfficiel twitter)

On 26 January former Zaire international Pierre Ndaye Mulamba, one of Africa's iconic footballers, died at the age of 70 in South Africa.

The news of his death prompted an outpouring of emotion on social media, which to some onlookers was ironic given the indifference shown towards him in the later part of his life.

His last few years were in sharp contrast to the early part of his life that saw him feted for his feats for club and country, including playing at the 1974 World Cup.

As the spotlight faded on the man whose record of 9 goals at a single Africa Cup of Nations finals still stands so the rumours and speculation about him increased.

"This is the story of a shining star that's overshadowed by issues of being African, being poor and being sidelined," his South African wife Nzwaki Qeqe said in 2010.

Ndaye's story begins in the central city of Kananga, formerly known as Luluabourg, where he was born and his football first began to blossom.

However he first had to win his reluctant father over in order for his career to progress further.

It took the intervention of an emissary from the government to sway the elder Ndaye to let his son attend a national team training camp but from then on, there was no looking back.

He joined giants AS Vita Club in 1972, a move that truly signposted the beginning of a golden period for him.

With the capital-based club, he won three domestic doubles, as well as the African Cup of Champions Clubs (the precursor to the Champions league) in 1973.

He had built up a fearsome reputation at home with Vita, but the 1974 Africa Cup of Nations afforded him the opportunity to make an even bigger splash.

"I was not [yet] famous like Kakoko [Etepe] Mayanga [Maku] and Kibonge [Mafu], because they've played so many times," he admitted.

"I was told [by the coaches] that 'they don't know you, so take advantage of it'."

His performance in Egypt left no one in doubt of his talent as he helped the then Zaire became African champions for only the second time in their history.

Ndaye's prowess in front of goal led them there: his nine goals remains a record for a single tournament haul to this day. He was, unsurprisingly, named the best player in the competition.

Zaire president Mobutu Sese Seko rewarded every member of the squad with a house each, as well as a Volkswagen Passat, following their momentous success.

Later that year, Zaire became the first team from sub-Saharan Africa to compete at the World Cup.

It was not, however, an impressive showing for either Ndaye or the team as a whole.

Pierre Ndaye Mulamba (13) was shown the red card at the 1974 World Cup in Germany as Zaire lost 9-0 to Yugoslavia

The striker was erroneously sent off in the second group game, a 9-0 hammering at the hands of Yugoslavia, and therefore missed the final group game.

Amid rumblings of unpaid bonuses and indiscipline, the Leopards exited the World Cup with no points and in disgrace, the abiding memory for many was Mwepu Ilunga rushing out of the wall and booting the ball away as Brazil readied a free-kick.

Despite the poor showing he was still a national hero with connections to Mobutu, and lived a relatively comfortable life in his Kinshasa home.

In 1994 the Confederation of African Football decided to honour his historic Nations Cup goal scoring feat on its 20th anniversary.

'The second half'

It was after he picked up this award that the second half of his life began and things started taking a turn for the worse.

In 1996 his house was stormed by armed men, who demanded money, as well as his Caf medal, when he could produce neither, he was shot twice in the leg.

The shots awoke his 11-year-old son Jeff who lost his life as he tried to intervene.

The harrowing incident saw him flee to South Africa with nothing, winding up in Cape Town where he made ends meet by being a parking valet and relying on the generosity of motorists.

As he disappeared from the public eye so the rumours about him began.

In 1998, a minute's silence was observed for him after a report that he had died in an Angolan mining accident, whereas he had been nowhere close.

The late Zaire international Pierre Ndaye Mulamba (left) was invited to events ahead of the 2010 World cup in South Africa when Danny Jordaan was CEO

His later life saw him confined to a wheelchair due to the gunshot wounds with his plight made worse by heart and kidney problems.

Ndaye found some comfort in his final days with his South African wife Qeqe and his stepson; the solace that his own nation, which he represented with such grace, had failed to offer.

"After all the honour I brought to the country I would prefer to stay in the bush in South Africa even if they gave me a grand house in a town in the DRC," he said.

"I am happy here (in Khayelitsha); I have freedom - real freedom."

He would, however, give in and returned without explanation to DR Congo in 2014 but things continued to deteriorate as he wound up, once again, in hospital.

Bedridden, unable to pay his bills or afford medication, he spent the last five years of his life crying out for help.

His pleas falling on deaf ears until it was too late: he eventually returned to South Africa, the adopted country that had given him a second chance at life, but only to die.

He became the fifth member of the 1974 squad to pass on after Kazadi Mwamba, Mwanza Mukombo, Jean Kembo Uba-Kembo and Mwepu Ilunga.

United by glory in the 70's, they would be united by poverty in later life; as all died in bitterness at the neglect they suffered at the hands of the government.

National heroes who gave up so much, including a formal education, in order to play football and bring honour to their country.

Before passing, they were forced to sell their houses and cars just to make ends meet.

It was an undignified, inauspicious end for one of the greats of African football, best captured in Ndaye's own words in the 2009 documentary 'Forgotten Gold', "A famous footballer, someone who was honoured in his country, who is recognised, how can he be forsaken like this?"

He may as well have been writing his own epitaph.

- Published26 January 2019