Footballers seek mental health help in record numbers

- Published

Burnley midfielder Aaron Lennon has spoken publicly about mental health problems

A record number of footballers are seeking mental health support, according to the Professional Footballers' Association.

PFA director of player welfare Michael Bennett expects the organisation to help "double or treble" the number of players in 2019 than it did in 2018.

Since January, 355 professionals have accessed therapy - the highest number ever recorded by the end of a season.

The figure for the whole of 2018 was 438, having risen from 160 in 2016.

Bennett says the increase is "a good thing" - as it shows increased trust in the PFA - rather than a growing problem.

He expects to see a spike in the number of players seeking help in the coming weeks as clubs decide who will not be retained for next season.

"When players go back to pre-season, that's when those who haven't got contracts realise they're struggling mentally, emotionally and financially," Bennett, who played professionally for several clubs, including Charlton Athletic and Brighton & Hove Albion, told The Next Episode podcast.

So what's it like to get released? And what support is out there when you do?

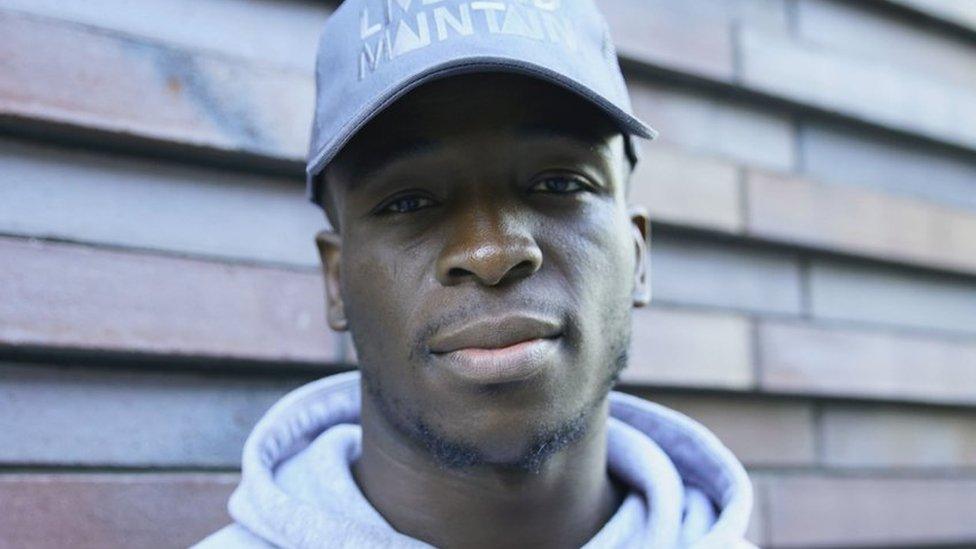

'I think they thought I was going to kill myself'

Olu Maintain was released by a Premier League side at 18. He'd been with the club since he was seven.

"I went crazy, because I thought it was a done thing," he says. "I was training with the first team. I wasn't even playing with a youth team.

"I'd spent my whole life at one place. How the hell do you expect me to mentally prepare?"

Maintain was told after a training session that he was not going to be kept on.

"It was a blur. I just remember walking out, I didn't even shower, just walked out," he says.

"I got my clothes on, got in my car and drove off. Then the head of the academy rang me because I think he thought I was going to kill myself or do something crazy.

"I spent my whole life there. They'd watched me grow up. I just couldn't accept it."

Maintain says he did get support from the club's coaches, but still found it tough.

"Mentally I wasn't in the space to hear anything from anyone," he says.

"That was the root of why my life spiralled out of control. A lot of my depression, a lot of mental health and all that stuff was me not dealing with rejection then."

Although Maintain went on to sign for Norwich and Falkirk, he feels the impact of that early rejection stayed with him.

"You're rubbish - that's how I took it. Point blank, you're not good enough for anything. Relationships, friendships, jobs," he adds.

"I'll start something now and never finish it. I can never see stuff through because I'm thinking it's just too good to be true.

"I'm worried about what people think. Worried about how people perceive me."

Since leaving the professional game, Maintain has begun writing a comedy series.

He still plays semi-professional football for Woking - who have just been promoted to the National League - but says the game still has a long way to go in tackling the mental health problems of some of its players.

"No-one wants to talk about emotions, and if you do you're soft," he says.

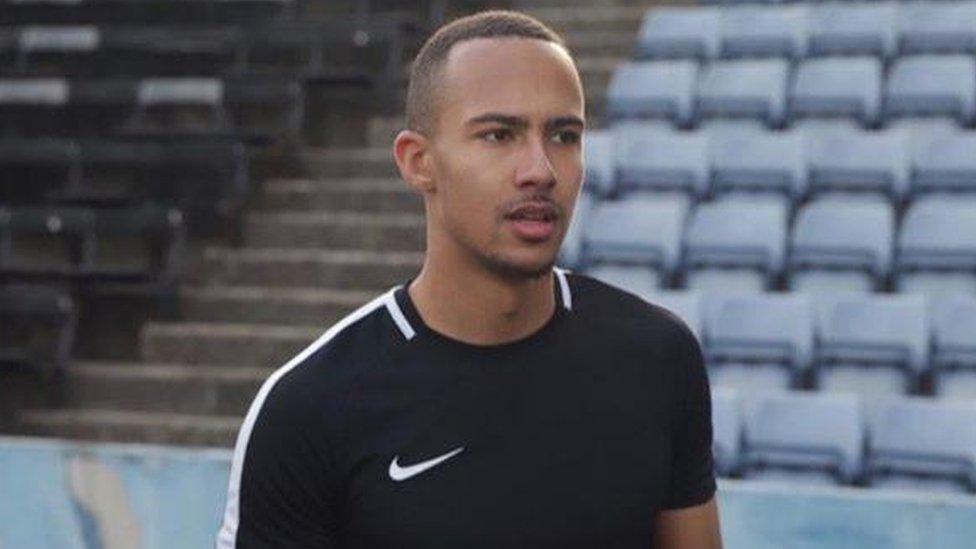

'I've seen players my age go to jail'

Andy Ali has been at the academies of four different clubs.

"I never actually had a contract," says the 21-year-old. "I was one of those players who was in for maybe two or three months."

At 16, Ali was at the academy of a Championship club and thought he had finally done enough to earn a pro contract.

"I thought this was finally the one that was going to pay off, so when they eventually told me [he was being released], I honestly I couldn't see a way forward," he says.

"I was thinking, 'how am I going to tell people what's happened?'

"No-one's your friend. One or two people might take a liking to you, but the system isn't there for you."

About 12,000 boys are in academies at any one time, and mental health provisions are being stepped up.

Any 16-year-old at a club has to carry on with some kind of education, and the PFA visits all 92 English league clubs to give workshops on mental health and emotional well-being.

The English Football League is halfway through a two-year partnership with mental health charity Mind, and on Wednesday the Football Association launched a new campaign using football to "generate the biggest ever conversation around mental health".

Ali is all too aware of the impact rejection can have on young players' lives.

"I've seen friends who were probably the best at football in my area go to jail," he says.

"I know one guy who made it as a pro at 18 and now he's in jail because he got released. He just couldn't accept that."

'You have to be strong mentally to play the game'

Maz Bettache manages Rising Ballers, a Sunday league team in west London including several players released by professional clubs.

"I was lucky enough to be part of a Premier League club from the age of nine up to 18 but unfortunately I didn't get a professional contract," he says.

"It didn't work out, but I bounced back and it's only made me a better person on and off the pitch."

The players at Rising Ballers say it feels a lot different to the professional academies they were at, in terms of the support network.

"When players get released, their life changes very, very quickly and it's hard to take," Bettache says.

"I'm just trying to create an environment for players to enjoy their football, showcase their talent and put it out there for the whole world to see."

Rising Ballers film all their games and upload them to YouTube. Their social media following is growing, and more and more scouts from professional clubs are watching the team, who are on a 21-game unbeaten run.

"That time when players have been told that they're not getting a professional contract is very crucial," says Bettache.

"It's about getting them opportunities with other clubs, opportunities away from football, different career paths and helping them, really helping them build up as a person again."

If you, or someone you know, have been affected by mental health issue, help and support is available at bbc.co.uk/actionline