Man City: The sliding doors moment that helped transform the club – 20 years on

- Published

Manchester City secured promotion to the second tier in 1999 thanks to goalkeeper Nicky Weaver saving a crucial spot kick

It's not the kind of thing you want to get wrong, so Nicky Weaver made doubly sure.

Before he took his place in goal to face Guy Butters' penalty, Weaver checked with the linesman.

"If I save this, is that it?" "Yes," came the reply.

The penalty was not a good one. Weaver went to his right, got two hands on the ball and kept it out. Manchester City had been promoted via the play-offs from the third tier.

What happened next is the stuff of legend.

Weaver was up on his feet, ran about five yards, then turned to his team-mates to urge them to join him.

Then he set off, arms waving manically, leaping over an advertising hoarding, pulling at his mustard yellow goalkeeper's shirt before quickly realising, with his gloves on, there is no chance of getting it off. Round to the City fans to the side of the goal, down the side, back on to the pitch before running into the arms of team-mate Andy Morrison, who wrestled him to the ground, where the remainder of City's squad piled on top.

"People always remember me for that celebration," said Weaver, now the goalkeeping coach at Sheffield Wednesday.

"I have no idea where it came from. I just waved the lads over and pulled this face I have never seen, before or after. This adrenaline was running through me and I didn't want it to end. I didn't know what I was doing.

"The last thing I wanted was 20 grown men piling on me but that is what happened. I am glad it did because people still talk about it now."

It is hard to believe now, as they celebrate the first clean sweep of major domestic trophies in men's football and their fourth Premier League title in eight seasons, but Weaver's save helped City get out of what, 20 years ago, was then called Division Two.

During that campaign, City hit the lowest point in their entire history when a 2-1 defeat at York dropped them to 12th in the table. The intervening years have not treated York so well. They have just finished 12th in National League North, the sixth tier.

Other lowlights of that campaign were Maine Road draws with Wrexham and Chesterfield, neither of whom are in the EFL at present, a one and, so far, only visit to Macclesfield's Moss Rose for a league fixture, and an attendance of 3,007 - the lowest in the club's history - for an Auto Windscreens Trophy defeat by Weaver's former club, Mansfield Town.

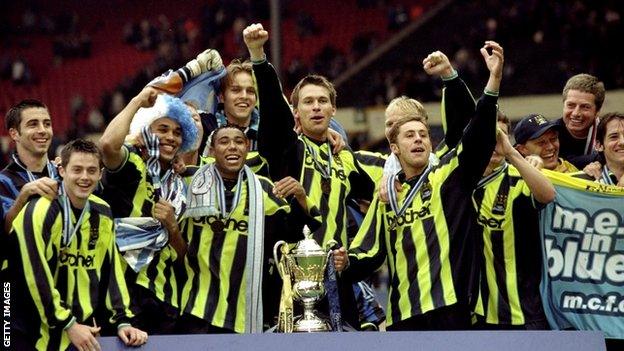

City had not won a trophy of significance for 23 years prior to securing promotion in 1999

"The Macclesfield game was like a concert," recalls Weaver. "They had a temporary stand up.

"It was difficult because it was everybody's cup final when City were in town and we found it difficult in the early part of the season. The fans must have been laughing inside because otherwise, they would have been crying."

The turning point was a 1-0 win on Boxing Day away to a Wrexham side that contained legendary Wales striker Ian Rush. City lost twice in the second half of the season yet Joe Royle's side still finished five points behind Walsall, who finished in the second automatic promotion slot, themselves 14 points behind champions Fulham.

It is impossible to know what would have happened to City if they had failed to beat Gillingham at Wembley.

Despite being in the third tier, City boasted the 13th highest average league attendance in English football during the 1998-99 campaign. The only non-Premier League club to exceed their 28,261 was Sunderland. None of City's rivals that season got half the number of fans through the turnstiles that they managed.

Manchester had already been confirmed as host city for the 2002 Commonwealth Games and it is generally acknowledged the stadium was a major factor in attracting investment of more than a billion pounds from Sheikh Mansour which has transformed the club's fortunes.

However, City did not agree to move in until three months after that play-off final.

Failure to beat Gillingham would have had immense financial consequences for the club, particularly as the following season they went straight up to the Premier League.

After Paul Dickov famously equalised in the fifth minute of injury time as City fought back from 2-0 down, there was a lot riding on that penalty shootout.

"It was my first year in the senior team so I had no experience of that situation," says Weaver. "I don't think I had even been in a penalty shootout in a schools tournament.

"Nowadays you look at where the last few penalties have been, you have all the statistics and information. There was none of that then. There was a lot of pressure. Gillingham's players weren't big time and I suspect to them, I must have looked a lot bigger and the goal a lot smaller. I just thought, 'make yourself look as big as you can, pick a way and go'."

Prior to that game, City had not won a trophy of significance for 23 years. Since 2011, they have won 10.

It barely feels like the same club. Yet many of the supporters who were so loyal two decades ago are now being rewarded with some of the finest football the English game has ever seen.

Because of that, what happened at Wembley in 1999 feels all the more remarkable.

"More people ask me about that day now than ever before," says Weaver.

"If City now were just a mediocre Premier League club, people wouldn't talk about it as much as they do. But the fact they are where they are just makes the story so much bigger and so much better.

"And what it also does is make the fans appreciate everything they have - the manager, the players, the style of football.

"Finishing second is seen as a rubbish season. Anything other than winning the Champions League is not what they want. A generation ago, it definitely wasn't like that."