The remarkable Mr Vokrri: Kosovo's football rise

- Published

- comments

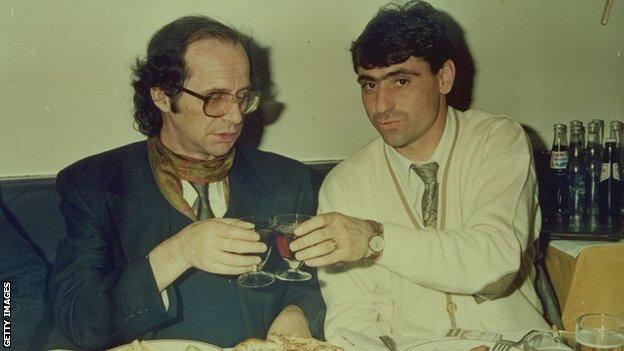

Fadil Vokrri (right) is considered the best footballer Kosovo has ever produced

All day the word "miracle" kept coming up. Maybe these thousands of people spilling out into Pristina's streets have just seen another.

It was September 2016 when Kosovo played their first competitive international football match.

On Saturday, they extended an unbeaten run to 15 games with possibly their most significant result yet - a 2-1 home victory over the Czech Republic. It is the longest such run in Europe.

Kosovo already have a very good chance of reaching Euro 2020. And their next qualifier is against England on Tuesday (19:45 BST). They are relishing the prospect.

This country of about 1.8 million people campaigned for eight years before being admitted as Fifa and Uefa members in 2016. The process began immediately after its declaration of independence from Serbia in February 2008. Some countries - including Serbia - still do not recognise its right to exist.

That such a young and troubled nation from the heart of the Balkans should shine on football's biggest stages was not the dream of only one man. But there is one figure who is revered here above all others - and his story helps explain the origins of this special team.

He was crucial to Kosovo's campaign for recognition as a football nation, and is a hero in his country. After his death last year at the age of 57, the national team's home ground was renamed in his honour: The Fadil Vokrri Stadium.

Like so many people here, Vokrri's life was marked by the war that still raged in this region only just over 20 years ago. By the bitter cycle of vengeance and counter-vengeance, and the tensions between ethnic Albanians and Serbs that still exist today.

And yet Vokrri was one of very few - perhaps the only one - able to communicate across the deep divides that cost so many lives. Football was his language.

When Vokrri was made president of the Football Federation of Kosovo he was starting from scratch. His offices were two rooms in a Pristina apartment block; two desks and two computers. It was 16 February 2008. Kosovo declared its independence the next day.

Vokrri was in charge of an association with no money, he had a national team that didn't have the right to play any official matches, in an isolated nation with little infrastructure.

What he did have was his reputation. He was the greatest footballer Kosovo produced - though that title may be challenged soon by the exciting new generation of talent that is emerging.

He was charming, charismatic and convincing. He and general secretary Errol Salihu were the campaigners the country needed.

"When we talked at home at this time, at the very beginning my father was thinking the process would be easy," says Vokrri's eldest son Gramoz, 33.

"Now we are recognised as a country, it will be fast, he thought. He soon realised it would be anything but easy, but he didn't mind it that way."

Gramoz lives in Pristina now. When he was old enough, he would often accompany his father and help with his work. Like his dad, he is well known in Kosovo's capital. Conversation is interrupted every five minutes as allies and acquaintances stop to say hello. Many stay much longer. Among them are government officials, football agents, and former generals in the Kosovo Liberation Army.

"My father never made a political declaration in his life and only focused on football. Football is higher than everything else - that was his vision," he says.

"It allowed my father to help achieve our goal - of entering Uefa and Fifa."

Vokrri was an adventurous forward with two good feet. If he wasn't the most prolific goalscorer perhaps his flair and determination made amends. He was loved by the fans. They recognised in him one of their own - even when he wasn't.

Gramoz Vokrri with his father. This picture was taken around six months before Fadil Vokrri died in June 2018

He grew up in Podujeva, a small city which today lies close to Kosovo's northern border with Serbia. Back then, just like the rest of Kosovo, it was part of Yugoslavia. He was born in 1960. During his childhood, Yugoslavia was a communist country made up of diverse nationalities, languages and religions, all more or less held together by its charismatic leader Josip Broz Tito., external

It was an age when Kosovar Albanians like Vokrri were rarely celebrated. They seldom became symbols of Yugoslav pride. But this talent was impossible to ignore.

Vokrri was the first to play for Yugoslavia - and he would be the only one. His debut came in a 6-1 defeat by Scotland and scored the goal, the first of six in 12 caps between 1984 and 1987.

He had started out at Llapi, his hometown club, before moving to Pristina. In 1986 he went on to Partizan Belgrade and stayed for three years - "the most beautiful" of his career, he said.

They won the league title in 1987 and the cup in 1989. In between, Italian giants Juventus came calling - but Vokrri was forced to turn them down. He hadn't completed the then-compulsory two years' military service, and so couldn't go abroad. He completed his duties while playing for Partizan, fulfilling light tasks during the week in between matches.

But leave the country he would, for reasons that were spiralling out of anyone's control.

Kosovan boys play football at an Intercampus training session in a refugees' camp in Albania during the Kosovo war, in June 1998

Many historians place President Tito's death as the key point in the collapse of Yugoslavia. They say he left behind a power vacuum which would be filled by resurgent rival nationalist factions.

Born in 1986, Gramoz was the first of Vokrri and his wife Edita's three children. By 1989, the family had decided they could stay in Yugoslavia no longer. Vokrri settled on the idea of leaving for France. In the summer, he signed for Nimes.

"At this time, everyone in Yugoslavia knew that war would happen," Gramoz says. "They just didn't know when or where it would start."

Years of suffering would define the next decade. During the 1990s, Yugoslavia was plunged into a bloody conflict in which as many as 140,000 people were killed.

From this fighting emerged the separate modern territories of today: Serbia, Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and the recently renamed North Macedonia. Kosovo was the last to declare itself an independent nation.

A scene from life in Kosovo's top flight in the mid-1990s as players wash after a match

Lulzim Berisha was 20 when he took up arms. He joined the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). It was 1998.

For the previous six years he had been in Pristina, still living under Yugoslav rule but playing football in what was an unofficial Kosovan top flight set up after the establishment of a separatist shadow republic there.

Matches were held on rough pitches in remote, rural locations. Fans would gather on sloping hillsides to watch. Serbian police would stop the players on the way and detain them for hours. But always somehow they managed to get word up the road for the opposition to wait. After the match, players would wash their muddy bodies in a nearby river.

This football league stopped when heavy fighting began in 1998.

"I decided to join the KLA because of my country," says Berisha. "I had no military experience but I saw many bad things happening here. That was the reason."

There was now open conflict between Kosovo's independence fighters the KLA and Serbian police in the region. It led to a brutal crackdown. Civilians were driven from their homes. There were killings, atrocities and forced expulsions at the hands of Serb forces.

The key turning point in the war came in 1999. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) had already intervened in Bosnia and it did so again in Kosovo. A 78-day bombing campaign forced Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic to withdraw troops and allow international peacekeepers in. Milosevic's government collapsed a year later. He would later be held at the United Nations (UN) war crimes tribunal for genocide and other war crimes carried out in Kosovo, Croatia and Bosnia. In 2006, he was found dead in his cell aged 64,, external before his trial could be completed.

After Serb forces left Kosovo in 1999, the territory remained under UN rule for nine years. About 850,000 people had fled the fighting. An estimated 13,500 people were killed or went missing, according to the Humanitarian Law Centre, external (HLC). The HLC, with offices in Pristina and Belgrade, continues to work on documenting the human cost of Yugoslavia's wars - including the civilian victims of Nato's bombardment.

As peace returned to the region, so did many of Kosovo's refugees. Children were named after then UK prime minister Tony Blair - rendered in Albanian as one single first name: Tonibler. There is enormous gratitude in Kosovo to the countries that intervened. Nowhere is it more obvious than on Bill Clinton Boulevard in Pristina, where a giant image of the former US president looks out across the traffic below.

Now 41, Berisha uses few words to describe his life as a soldier and the violence he witnessed.

Lulzim Berisha at the Dardanet cafe and bar in Pristina

Today he is one of the main personalities behind the Kosovo national team's biggest fan club: Dardanet. The name means "the Dardanians" - the people of an ancient kingdom that ruled here.

Dardanet have just opened a new cafe bar that serves as their headquarters. Opposite an old tile factory whose chimneys rise high into the sky, the call to prayer from a local mosque carries over lively conversation between the animated chain-smokers gesturing in their outside seats. The other fuels are dark black espresso coffee and conversation about football of any kind. Serie A is no longer the most passionately discussed. That would be the Premier League.

Lulzim sucks sharply on his teeth as a staccato point at the end of each short sentence.

"We want every kind of people to come to the stadium. Every game we give 100 tickets for free to female fans. We want families to come," he says.

On the table next to us, a reel of tickets for the England match in Southampton is unfurled with glee. They arrived that morning. The visas to travel are through too. Lulzim explains there will be a match against an English fan club, England Fans FC, in Hounslow on Monday, before Tuesday's Euro 2020 qualifier at St Mary's.

Inside, the walls are packed high with framed photos of Kosovo players, new and old. Vokrri's image is everywhere. They describe themselves as "Children of Vokrri". He has become an icon for the fan club. They produce banners, T-shirts and online posts that carry his image under messages such as: "Looking down on us."

"Vokrri is a legend," says Berisha. "He is our hero. For everything he did. For the people."

But pride of place in the fan club bar belongs to the match shirt worn by Valon Berisha when he scored Kosovo's first goal in official competition. That was a 1-1 draw in Finland, a 2018 World Cup qualifier played in September 2016.

It was the culmination of many years' hard work. Not so long afterwards, it looked like things would only go downhill.

Vokrri returned to Kosovo from France about five years after the war ended. With him at the helm, football's world governing body Fifa turned down Kosovo's first attempts towards membership in 2008. At that point the country had only been recognised by 51 of the UN's 193 member nations. It seemed a majority would be required.

Instead, they continued to play unofficial matches against unrecognised states: Northern Cyprus, a team representing Monaco, a team representing the Sami people of north Norway, Sweden, Russia and Finland.

The players at this time were drawn almost exclusively from the domestic pool. People who had been forced to flee their homes only a few years ago, or who had taken up arms and fought.

There was another way. One that was still tantalisingly out of reach.

"In 2012, when Switzerland played a match against Albania, 15 of the players on the pitch were eligible to represent Kosovo," Gramoz says.

"My father was at the game, watching with Sepp Blatter, then the Fifa president. Mr Blatter said to my dad: 'How are you enjoying the match?'

"He replied: 'It's like watching Kosovo A versus Kosovo B.'"

The major step forward came in 2014, when Fifa allowed Kosovo to play friendly matches against its member nations - as long as certain conditions were met. There was still significant opposition from Serbia.

Mitrovica was the location for Kosovo's first recognised friendly match. This city, with local Albanian and Serbian populations divided in two by the Ibar river, still requires the presence of Nato troops today, 20 years on from their arrival as a peacekeeping force. Oliver Ivanovic, a prominent politician seen as a moderate Kosovo Serb leader, was shot dead outside his party offices there in January 2018.

Albania goalkeeper Samir Ujkani chose to accept a call-up, as did Finland international Lum Rexhepi, Norway's Ardian Gashi and Switzerland's Albert Bunjaku. The opposition were Haiti. It finished 0-0.

"For us, it was a big, big victory," says Gramoz.

"It was a clear message from Fifa. The moment they allowed us to play friendly matches we took that to mean: 'Don't stop, you will enter as full members - but we need time to prepare people.'

"Even if we didn't have the right to play our national anthem, it's OK. We play football. That was the most important thing.

"First of all friendly games. After that, our delegation was invited to a Uefa congress for the first time. My father went to the Ballon d'Or ceremony. We had indications that the work was going well."

In May 2016, all the determined efforts, all the canvassing and campaigning done by Vokrri and Eroll Salihu finally came to fruition. Kosovo were admitted as full members, first of Uefa, then of Fifa.

"The whole country stopped. Everything," says Gramoz. "After independence, it was the biggest thing that's happened in Kosovo.

"People started throwing fireworks, pouring out into the streets. It was like we won the World Cup."

At the Uefa vote, there were 28 in favour and 24 against, plus two invalid votes. Serbian Football Federation president Tomislav Karadzic said the result would "create tumult in the region and open a Pandora's box throughout Europe". It challenged the ruling at the Court of Arbitration for Sport. Uefa's decision was upheld.

Now Kosovo had an official national team, it could take part in the upcoming qualifiers for the 2018 World Cup. But what would the team look like?

Kosovo delegation members react emotionally after receiving Uefa membership in May 2016

In June 2016, at the European Championship in France, Albania and Switzerland met again.

Among the Swiss side were Arsenal's Granit Xhaka and Xherdan Shaqiri, now of Liverpool. Xhaka's elder brother, Taulant, played for Albania. Each of these - and several more - might have decided to switch allegiances and join the new Kosovo team.

Uefa said it would consider applications to do so on a case-by-case basis. The Swiss FA released a statement complaining that Kosovo was unsettling its players. Gramoz believes Uefa's strategy was a concession to those member nations worried about losing talent.

"Uefa and Fifa never said publicly that they all had the right to play - even though every application was successful," he says. "It was very diplomatic."

Xhaka and Shaqiri - perhaps the two best known eligible players - decided to stay with Switzerland. For those who did make the switch, the process did not go as smoothly as planned.

Five hours before kick-off in Kosovo's first competitive match, the team was still awaiting clearance for six players - including one of their most promising, Valon Berisha, who had already played 19 times for Norway.

It was 5 September 2016. Eventually the clearance came through. Berisha played and scored the equaliser in a 1-1 draw in Turku on Finland's west coast. It was an encouraging start, and a hugely emotional moment for players, fans and the country.

But Kosovo were beaten heavily in their next qualifier, 6-0 by Croatia - one of several home ties played in the Albanian city Shkoder. The national stadium in Pristina needed work to meet the required standards.

The draw in their first match against Finland would be their only point of the campaign. Kosovo finished bottom of their group, suffering nine consecutive defeats.

They had got a tough draw and, back then, perhaps it felt like just taking to the field was a victory.

Now the picture is very different indeed.

The day before Saturday's game there is a thunderstorm in Pristina that flashes back against the black night sky, recalling a very different time from not so long ago. Peace lives here now. Even when the rain does fall it doesn't bother the children chasing each other along the city's central street, no matter the risk to their ice creams.

Down below, the stadium's floodlights are lit. Kosovo are playing the Czech Republic the next day. Something very strange is about to happen.

The following morning, reports surface about arrests the police have made. Eight Czech fans were allegedly found with a drone, a Serbian flag and a banner reading "Kosovo is Serbia". It seems a revenge stunt was planned.

In 2014, a drone flew over the Belgrade ground hosting a match between Serbia and Albania. It was carrying a banner labelling Kosovo part of "Greater Albania". There was outrage. A mass brawl broke out on the pitch, fans streamed in from the stands and lashed out at players. The match was abandoned and Albania were eventually awarded a 3-0 default win.

Shortly after news of the arrests breaks, the Dardanet fan group responds. "We invite prudence and restraint," they say. "Any potential incident could harm Kosovo."

There is instead a happy ending.

Riot police had to be brought in to restore calm but the Serbia-Albania match was abandoned, as Wendy Urquhart reports

Going into the match, Kosovo are unbeaten in 14 games. Their last defeat was in October 2017. Six of those matches came in the inaugural Uefa Nations League, where performances have already guaranteed them a place in the play-offs for a spot at the Euro 2020 finals.

Georgia, North Macedonia and Belarus are the three other teams likely to contest Kosovo's section of the play-offs. Only one of those countries recognises Kosovo - its southern neighbour North Macedonia.

Uefa currently keeps Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina apart from Kosovo for security reasons, but all other countries must play them. Uefa will allow a team to request their home fixture be played on neutral territory - as happened when Ukraine and Kosovo met in Poland in a World Cup qualifier in October 2016.

As for what happens should Kosovo reach Euro 2020, four of the 12 nations hosting games in next year's tournament - Azerbaijan, Romania, Russia and Spain - do not recognize Kosovo's independence either.

And it is beginning to look like they will make it. They might even end up qualifying automatically.

Come kick-off time, the Fadil Vokrri Stadium is packed. Tickets apparently sold out completely in 15 minutes.

Men in uniform are watching the sky through binoculars from the top of a high building opposite. There are no drones in sight. On the other side, a group of children have outdone them, perched atop an unfinished tower block that stands a good 10 storeys tall. The bent steel tips of its exposed reinforced concrete stretch higher above them still.

The Czechs take the lead. Arijanet Muric, the Nottingham Forest keeper on loan from Manchester City, is beaten by Patrick Schick's delicate finish inside the box.

But the home fans rally their team. Their passion is raw and irresistible, and it runs through the Kosovo side and harries them forward. There are rash challenges, hurried touches at the vital moment. There is the bravery to persist, the drive to force their opponents back again and again.

Kosovo's 68-year-old Swiss manager Bernard Challandes - appointed by Vokrri in March 2018 - is the only calm presence around. The whole ground is constantly carried away, including everybody who isn't Czech in the press box.

Even when Vedat Muriqi gets the equaliser before half-time, Challandes keeps his cool. But when Mergim Vojvoda stabs the home team in front from a short corner there is a volcanic chain reaction of emotions: joy, pride, delight. Challandes cannot resist. The substitutes are up from the bench. The injured players who travelled to be with their team leap forward too - only a little more carefully.

With the final whistle approaching, the Czech Republic fashion four good chances in about three minutes. In extremely polite English totally at odds with the situation, the Kosovan journalist next to me says: "Phew, that was close."

Five minutes of added time. Superstition kicks in. Fenerbahce striker Muriqi - a huge presence - hauls his team up the pitch, protecting possession like he has been for what seems an eternity. Challandes is gesturing wildly now, like everyone else.

And then the stadium erupts. The players hug each other. Challandes is under a mountain of tracksuited bodies. There is a long and reflective lap of victory. England are next. They cannot wait.

The Dardanet members wave their banners and sing their songs. The Children of Vokrri will go home very happy tonight - eventually.

When Vokrri died last June, having suffered a heart attack, his burial was marked by a special state ceremony in Pristina., external

"Some Serbian officials came to his funeral, including the former FA president Tomislav Karadzic. It's very rare to make a visit like that," Gramoz says.

"Afterwards, Partizan Belgrade invited me to visit them. I went to Belgrade, and they showed me huge respect. They didn't care if I was Albanian, they told me I was part of their family, because of my father.

"This is why I think, especially here in this case between Kosovo and Serbia, we should use sports and football to promote relations between the countries.

"It will be a great victory for our national team the day when a Kosovan Serb lines up with us on the pitch."

Gramoz is perhaps like his father in that he likes to dream. But football can do powerful things. Here it has already done so much.

Kosovo fans celebrate their latest victory. The country has the youngest population in Europe with half its people under the age of 25

The conflict in Europe that won't go away: Three BBC correspondents explain the Kosovo war two decades on

The 'Heroinat' ('Heroines') monument in Pristina honours the contribution and sacrifice of every ethnic Albanian woman during the 1998-1999 war in Kosovo

Ibrahim Rugova (left) became president of Kosovo's separatist republic in 1992. Vokrri's status as a footballer assisted him in his diplomatic efforts abroad - here the two are pictured in Turkey. Vokrri played for Fenerbahce from 1990-1992

Red Star Belgrade fans display a banner reading: 'Kosovo is Serbia' in a Uefa Cup match at home to Bolton in 2007

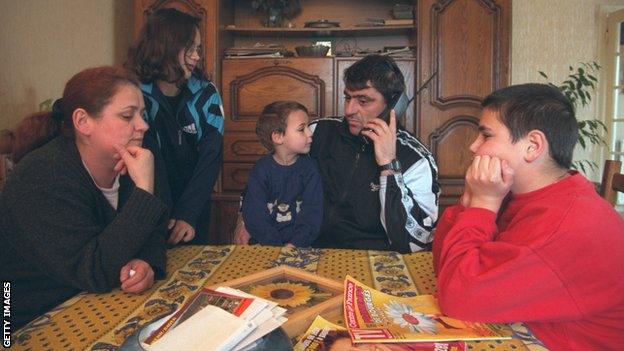

Fadil Vokrri and his wife and children lived in Montlucon in France during the Kosovo war. Vokrri was the coach of Montlucon FC. Gramoz says his father was constantly checking on family back home

Flamurtari FC's football stadium in the Kosovo capital of Pristina. They finished sixth in the Kosovan top flight last season

Salihu (L) and Vokrri (R) waiting at the Uefa congress in Budapest in May 2016, when Kosovo was about to be made a member nation

- Attribution

- Published17 February 2018

- Attribution

- Published25 November 2022