Liverpool win Premier League title: Why a 30-year wait seemed unthinkable

- Published

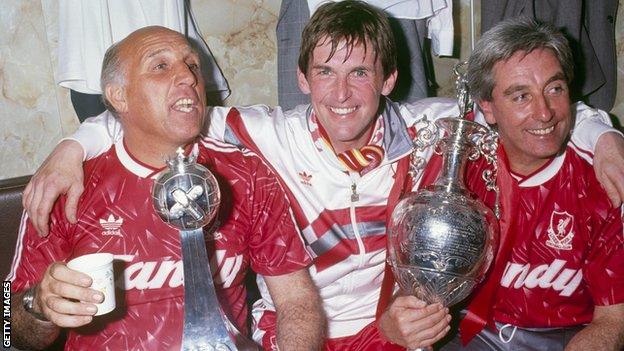

Liverpool's 1990 triumph was their 11th top-flight title in 17 years

"Liverpool are champions again and it is difficult to see what will prevent the same words being written again this time next year."

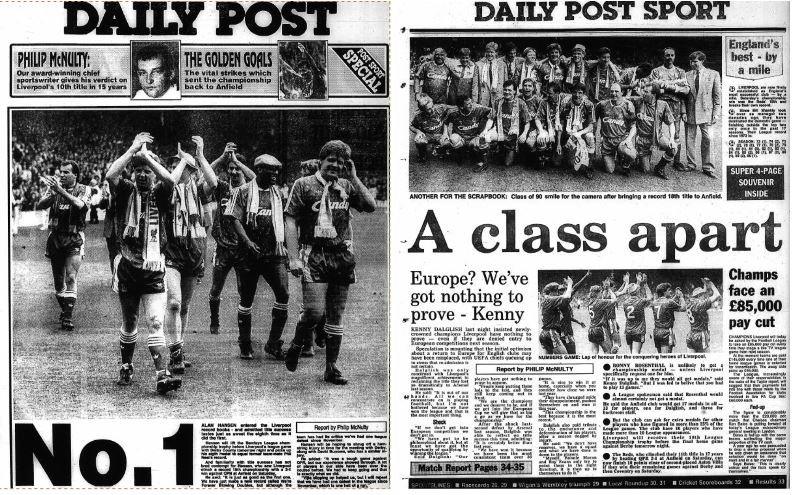

This is not the final verdict on Liverpool's relentless march to a first Premier League title. They are this reporter's words in the Liverpool Daily Post on Monday, 30 April 1990, two days after the Reds had secured their 18th league crown with a 2-1 win over Queens Park Rangers at Anfield.

It was the last time they would celebrate such a success for three decades.

No-one, least of all those in Anfield's cramped old press box, would realise how different life would soon be for the newly crowned champions, managed by Kenny Dalglish and boasting iconic figures such as Alan Hansen, Ian Rush and John Barnes.

The crowd was a less-than-capacity 37,758. It was a routine occurrence and reporting on this sort of occasion had also become a matter of course for a very young chief football writer covering Everton and Liverpool.

Liverpool's title success was front-page news on 30 April 1990 in the city's Daily Post newspaper

There had been Everton's title win in 1986-87. Liverpool sealed a blistering triumph - fuelled by Barnes and Peter Beardsley - the following year. Then there was Michael Thomas' stoppage-time "it's up for grabs now" goal for Arsenal on a warm Friday night in May 1989 that denied hosts Liverpool the league and FA Cup double in the aftermath of the Hillsborough disaster. Everybody assumed 1990 was a resumption of normal service.

Looking back now, it seems small cracks had appeared and we had started to notice them.

"If the title champagne is in keeping with their season, it will not be vintage but it will still be highly satisfactory."

But any shortcomings were disguised by an 18th English top-flight success.

If anyone inside Anfield - or indeed outside - had suggested it would be 30 years before these celebratory scenes were replicated it would have been dismissed as fantasy.

Winning titles helped feed Liverpool's soul. Little did they know how long they would be starved.

The club have rarely been without hope in intervening years which have brought all the other major trophies - but, in a title context, it is the hope that has killed them.

And even on the brink of this crowning achievement, when they stood just six points from their goal, the global coronavirus pandemic halted the season and added another three months to the waiting time, leaving the most pessimistic supporters fearing the season could be declared null and void.

They could barely dare to dream - until now.

The post-Dalglish decline

It was the morning of Friday, February 22 1991 when a phone call came through to the Daily Post sports desk from Liverpool's legendary secretary and later chief executive Peter Robinson, whose unsung, tireless contribution underpinned their successes.

"You need to come up here this morning as soon as you can," the man known inside Anfield as "PBR" told me. "And don't hold the back page. Hold the front as well."

The guessing game began but few hit on the real reason for the sudden summons - Dalglish was resigning.

The Scot, worn down by the burden of maintaining Liverpool's success while he and his wife Marina devoted themselves to helping supporters after the Hillsborough disaster at the FA Cup semi-final against Nottingham Forest in 1989, needed time away.

The man who had won three titles and an FA Cup as a manager was hardly leaving Liverpool in a state of disrepair. After all, they were still top of the league and had conducted a breathless 4-4 Merseyside derby draw at Everton in the FA Cup less than 48 hours earlier.

But this, we can now see, was a pivotal day in Liverpool history.

Even before the advent of social media, the rumour mill was in full swing suggesting Dalglish had fallen out with the club's hierarchy or his players.

Not one bit of it was remotely true.

Indeed, so protective was he of Liverpool's reputation and of those left behind, that even on one of the saddest days of his career, when the same Daily Post phone rang at about 5.30pm that evening, it was Dalglish wanting to make clear this was not the case.

Graeme Souness, Dalglish's Liverpool team-mate in five title and three European Cup triumphs, succeeded him in April. It was an appointment greeted with unanimous approval from Liverpool fans.

Souness was the decorated former captain who had transformed British football at Glasgow Rangers, winning trophies while reversing a time-honoured trend by luring England internationals like Terry Butcher, Gary Stevens, Trevor Steven and Chris Woods north of the border.

Still short of his 38th birthday, he blew in like a hurricane - but, as he later admitted, the hurricane hit too hard and too fast.

The Scot's modernising methods on diet, approach, and even the renovating of the dilapidated Melwood training HQ - Liverpool's players still changed at Anfield and took a short coach trip to the old base three miles away - did not cut through with many in a squad who used to be his team-mates.

Souness had so many ideas that made good sense. He erred by trying to implement them too quickly.

He gave young players such as Robbie Fowler, Steve McManaman and Jamie Redknapp their chance.

However, there was a storm of another kind brewing 35 miles away - at Manchester United under Sir Alex Ferguson - that helped condemn Liverpool to 30 years on the title margins.

According to Souness, Robinson once said: "If that lot down the East Lancs Road ever get their act together we're in trouble."

They did. And they were.

Souness' side won the FA Cup in 1992, with their boss on the touchline as he recovered from triple bypass heart surgery a month earlier.

But even that was overshadowed by his exclusive story appearing in The Sun on the anniversary of Hillsborough, a newspaper that caused outrage and was then widely boycotted on Merseyside for its coverage of the disaster.

A victim of circumstances and timing who would never knowingly have offended Liverpool's fans in such a fashion, Souness has apologised many times - but his relationship with many supporters was damaged forever.

Those of us who dealt with him on a daily basis and liked him saw a driven individual who burned with the passion to bring titles back to Anfield. He could not and left in January 1994.

Roy Evans, labelled "the last of the bootroom boys" when promoted from his role as Souness' right-hand man, was another destined for frustration as the United superpower grew stronger and Arsenal emerged under Arsene Wenger.

Evans managed with a lighter touch - is it actually a criticism to say someone is too nice? - and won the League Cup in 1995, but Liverpool's combination of older heads, youthful talent and big buys, such as the maverick Stan Collymore, were flawed when it came to the Premier League.

Too much of that era was wayward on and off the field, the garish white suits commissioned for the 1996 FA Cup final defeat by Manchester United becoming the symbol of a team that should be remembered for far more.

Liverpool had the 'Spice Boys'. Manchester United had the Class of '92.

One was more style than substance. The other had both.

Evans had a team and a squad that could never quite be trusted - hugely talented but fatally fragile.

The Houllier reboot

Gerard Houllier, left, was Liverpool's first non-British or Irish manager

It was time for more change at Liverpool - and it arrived in unorthodox fashion on 16 July 1998 when Gerard Houllier, fresh from playing a part in France's World Cup triumph, was appointed joint-manager alongside Evans.

Again, I was the beneficiary of another Robinson phone call, suggesting I come to his office to "meet someone interesting".

I was the first journalist to meet Houllier and, as he put it, he could not wait to meet his "new family".

The appointment was years in the making. Robinson had forged a long friendship with Houllier and made his move when Celtic and Sheffield Wednesday failed to lure the Frenchman.

It was a sort of homecoming for a man who had stood on the Kop watching Bill Shankly's Liverpool during his days as a French teacher at the city's Alsop Comprehensive School 30 years earlier.

There were some inside the club who questioned how it would work even on the day he arrived. The answer was simple: it didn't.

The arranged marriage did not last. Evans left in November.

Houllier's pursuit of perfection was all-consuming - so much so that he almost paid with his life.

Every waking thought was Liverpool, even ringing my flat at 7am one Sunday as he agonised alone at Melwood over a substitution - one in this instance he had failed to make - involving Sami Hyypia in a 1-1 draw at Manchester United in March 2000.

When asked to preview Euro 2000 for this website, Houllier insisted on a face-to-face meeting after hours at the training ground, producing pages and pages of hand-written documents assessing each team and key players.

It was a window into his approach. Meticulous. No detail too small.

Houllier remains underrated and under-appreciated by many, but his legacy can be gauged in the way he shaped the professionalism and approach of Jamie Carragher and Steven Gerrard, to name but two.

He revamped the dressing room, not just in bricks and mortar but also personnel.

Out went over-bearing and over-influential figures such as Paul Ince and Neil Ruddock; in came seasoned professionals such as Gary McAllister, a free transfer masterstroke, along with Hyypia and Stephane Henchoz, the outstanding central-defensive partnership.

Houllier brought silverware, including a treble of League Cup, FA Cup and Uefa Cup in 2001.

Being around Anfield at the time was to detect the feeling the good times were back. The title was a serious option once more.

Sadly, Houllier was taken seriously ill during a home draw with Leeds United in October that year and required 11 hours of life-saving heart surgery.

In convalescence at home, he still had his eyes on Anfield affairs. Calls made to ask about his health took a matter of seconds to turn to football.

Houllier returned the following March, but he was back in his post too soon and his reign never regained momentum, even though Liverpool finished that season in second place.

The sure touch had gone. Signings such as El-Hadji Diouf, Salif Diao and Bruno Cheyrou failed.

Houllier talked about his Liverpool team being "10 games away from greatness" before a Champions League quarter-final against Bayer Leverkusen in April 2002, when they were also one point off the top of the Premier League.

Less than prophetic words. Liverpool lost to Leverkusen, then came up short in the title race. It was never quite the same again.

The Reds won another League Cup under Houllier, beating Manchester United in the 2003 final, but progress had stalled when he left at the end of 2003-04.

So near and yet so far - until now

Rafael Benitez took Liverpool to two Champions League finals, winning one, but his best league finish was second place in 2009

Every August it is the same question: are you tipping Liverpool again this year?

It all goes back to a fateful pre-season prediction made in August 2009 on these pages that Liverpool would end a 20-year wait for the title.

Every subsequent Liverpool 'failure' saw it revisited - but it was not a claim made without foundation.

Liverpool had finished second - four points behind Manchester United - the previous season. They had lost only two league games, and also recorded a 4-1 win at Old Trafford in the same week Real Madrid were thrashed 4-0 at Anfield.

All seemed set fair. Except that it wasn't.

Spaniard Rafael Benitez, whose "facts" monologue, external - it was not actually a rant - against Manchester United manager Ferguson in January the previous campaign had taken Liverpool's eyes off the ball briefly but significantly, had scored a spectacular own goal.

The manager had a fragile relationship with mercurial midfielder Xabi Alonso, the supply line for Gerrard and Fernando Torres, and it led Liverpool to sell him to Real Madrid in the summer of 2009. In another ill-judged move, Benitez replaced his compatriot with the easily breakable and mostly redundant or injured Italian Alberto Aquilani.

I recall the sight of a concerned Benitez trying to reassure fans outside Anfield after an early-season home defeat by Aston Villa. How those concerns were justified.

The club had started to creak under the folly of owners Tom Hicks and George Gillett. Liverpool's best days under the manager who brought them the Champions League in 2005 and the FA Cup the following year were gone.

The season that should have made up for a near miss was miserable. Liverpool finished seventh. Benitez was sacked.

Roy Hodgson and the returning Dalglish were in a holding pattern without title aspirations, although the latter won the League Cup in 2012, until the next near miss that came from nowhere.

Brendan Rodgers succeeded the sacked Dalglish in summer 2012 - appointed by the latest owners, Boston-based Fenway Sports Group - and promising early work came to a peak in the second half of the 2013-14 season.

Rodgers was denied the sort of legendary status reserved for the club's title-winning managers by an infamous slip from one of Liverpool's greatest players.

Liverpool were fifth at the turn of the year but there was a feeling of huge confidence around the club based on the brilliance of Luis Suarez, the goalscoring gifts of Daniel Sturridge and the teenage tyro Raheem Sterling.

Rodgers was a confident leader and Liverpool hit the top with six games left.

An atmosphere bordering on hysteria was sweeping Anfield, especially as closest rivals Manchester City were beaten 3-2, leaving Liverpool top with only four games remaining.

And then, with the title within their grasp, Gerrard's slip against Chelsea let in Demba Ba as old nemesis Jose Mourinho revelled in wrecking the party.

Steven Gerrard would end his Liverpool career without the one trophy he craved the most

Liverpool were still top but City suddenly had the advantage and an old uncertainty - Rodgers had never cured defensive failings - saw a 3-0 lead conceded in 11 minutes at Crystal Palace.

Never had a manager who was top of the Premier League with one game left looked so desolate.

The dream had died again, emphasised by the sight of a broken Liverpool manager staring blankly into space in Selhurst Park's media suite.

It had receded into the distance again and would only return following Jurgen Klopp's magnificent rejuvenation, which took last season to the final game.

And now the title those of us predicted would follow swiftly 30 years ago has returned to Anfield.