Major League Soccer: American league's setbacks & successes, on eve of 25th season

- Published

- comments

Beckham - then aged 32 - arrived at LA Galaxy in July 2007

After all the slick presentations, after David Beckham has swept in and charmed the 40th floor of a Manhattan hotel, it is hard to believe that, not so long ago, Major League Soccer came close to falling apart.

That Beckham - or Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Wayne Rooney, Kaka, Andrea Pirlo, Thierry Henry and Steven Gerrard - might never have come as players. That there might have been no Seattle Sounders, Atlanta United or Inter Miami - the team Beckham now represents as owner.

MLS was celebrating the approach of its 25th season this week. Oscar-winning composer Hans Zimmer has created a new anthem to mark the anniversary.

However, in 2001, it was "on the brink" of collapse, recalls MLS commissioner Don Garber.

"We were with bankruptcy attorneys sitting around a table," Garber says. "The league was as close to folding as a signature on a page. If it had, it would likely never have come back.

"Rarely in life do you get the chance to put all your chips on the table and go all in. We did, and we won the pot."

Fast forward to today, and one owner bullishly describes the MLS as the United States' third most popular spectator sport. He predicts it will be one of the top five football competitions in the world within 10 years.

Six new teams are to join by 2022 - two a year. Seven new stadiums will be opened. There is no Las Vegas yet but it does have a 'Nash Vegas', as Nashville is amusingly known because of its impressive number of bars and lively night life. MLS is on the march.

For obvious reasons, former England captain Beckham is viewed as the most significant figure in MLS history. But that doesn't tell the whole story.

The last quarter of a century of football in America is a tale of chaos, hope and despair. Of financial catastrophe, blind faith and a rebirth that seemed barely imaginable.

"I didn't have football posters on my wall as a kid," says Alexi Lalas. "It was mostly hockey players. My English influence was Joe Elliott from Def Leppard. I didn't grow up with the dream of being a soccer player."

For kids growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, it was a similar story across America as a whole. USA team boss Gregg Berhalter remembers heading to Paterson to watch the New Jersey Eagles play in the late 1980s. The stadium was a bowl, with an athletics track, that was primarily used for baseball.

"There were national team members playing," he says. "You are talking about a semi-professional side playing on turf at a high school stadium. The only alternative was to go abroad. That's how it was."

Lalas, 49, was the face of pre-MLS soccer in the country. With his distinctive ginger hair and long beard, he was already hard to miss. But his performances in defence for the USA when they hosted the 1994 World Cup introduced him to a new audience.

By the time of the first MLS season in 1996, professional soccer had been absent from the US for 12 years - the old North American Soccer League had disbanded in 1984. That Lalas was able to return was a direct consequence of world governing body Fifa making the creation of a new league a condition behind World Cup hosting rights.

Alexi Lalas, pictured with New England Revolution in March 1997. New England had the league's highest average attendance that year - 21,423 in a 60,000 capacity ground designed for NFL

"There had been a lot of talk about it for a while, but nothing seemed to happen. I just knew if a league did start, I wanted to be part of it," he says.

New England Revolution brought Lalas home from Italy, where he had been playing his club football with Padova, for the debut 1996 campaign. He moved on four times after that and ended his career with three seasons at LA Galaxy from 2001.

"It was a type of Wild West existence," he recalls of those early years. "I vividly recall training in the parking lot at the Rose Bowl. We were using American football stadiums, with all the lines, and the training facilities were absolutely rudimentary. Many players were barely earning a liveable wage. It was a labour of love."

There were also notable differences in how the game was played. There was a countdown clock that struck zero at the end of each half, with the referee stopping their watch when the ball went out of play. Penalty shootouts were used to decide drawn matches, with players taking on the goalkeeper - and a five-second timer - in a one on one starting from 35 yards out.

The idea behind these innovations was to jazz up the game, but 'Americanisation' infuriated and alienated in equal measure. Domestic fans, particularly the younger generation, felt they weren't being presented with an authentic experience. Established football communities across the world treated the rules - and by extension the league - as a joke.

A September 1996 MLS game between New York-New Jersey Metrostars and LA Galaxy - with NFL markings on the pitch

By his own admission, Garber was a "career sports marketing guy" with "next to zero" soccer knowledge when he left a senior vice-president's role at the NFL to become MLS commissioner in 1999.

But he quickly understood that the competition needed to adopt the universal rules of the game. The countdown clock was ditched, as were the penalty shootouts. An increased number of substitutes was also scrapped.

By 2001, MLS was recognisable to the rest of the world as a football competition. But it was haemorrhaging money. An estimated $250m (£191m) was lost across those first five turbulent seasons.

When MLS launched, it had done so in NFL or college American football stadiums. The lowest capacity was 30,000, the highest just over 100,000. The average attendance across that first season was 17,406. By 2001, the figure had slipped to 14,961. In the play-offs, six crowds were under 10,000.

It was not an attractive look, and it was against that backdrop that the desperate calls surrounding the future of the league were made. Billionaire businessmen Phil Anschutz, Lamar Hunt and Robert Kraft stepped in.

Anschutz took control of six teams, Hunt took over three and Kraft kept New England Revolution alive. If they had chosen another path, the game would have died. As it turned out, Miami Fusion and Tampa Bay Mutiny folded anyway. Florida, it was decided, was not a viable MLS state at that time.

With 10 teams and three owners, the league regrouped and went again. From thinking he had made a terrible career decision by leaving the NFL, Garber was optimistic again.

"Once I knew they were there, I was committed," he says. "I was a young guy and I had nothing to lose. I started believing in my core, then it became a passion play and there was no way either I or the people around me were giving up. I hate to lose. I would have hated to admit failure."

MLS moved forward tentatively for the next six years. Then, in 2007, the pace of progress changed dramatically - with the arrival of one man.

Chris Klein can still remember finding out Beckham was moving to MLS.

In January 2007, he was with the Kansas City Wizards. He had no idea that six months later he would be traded to LA Galaxy and form a friendship with Beckham that exists to this day. Klein was even a pivotal figure in the famous statue stunt played on the former Manchester United and Real Madrid midfielder by Late Late Show host James Corden, which has over 28 million views online.

"I was sitting in our bedroom at our house with my wife," he says. "Even she was completely blown away. She wouldn't know the vast majority of players if she was sitting next to them. But David Beckham? Instantly she knew. I just knew it was going to change the league."

Beckham made his first LA Galaxy appearance in a friendly against Chelsea on 21 July 2007

Klein had been traded to the Galaxy by the time Beckham's move from Real Madrid came into effect. The specially created "designated player rule" allowed the deal to exist outside the salary cap and was quickly dubbed "the Beckham rule". It is the vehicle still used to sign higher-profile players and, in 2020, each team has the option to sign three each.

"He came into the dressing room wearing a finely tailored suit," says Klein of Beckham's arrival in July 2007.

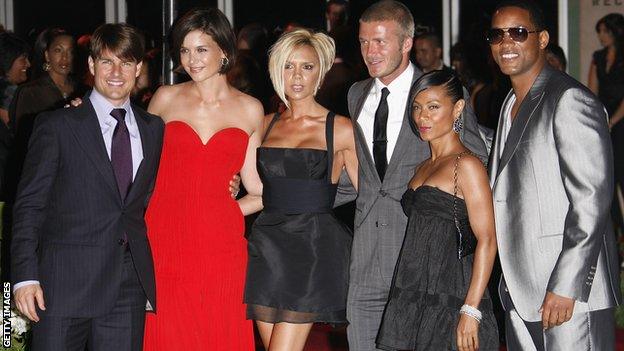

"He was a gentleman and very gracious, someone who wanted to be part of the team. But even in the first couple of weeks, we were being invited to parties being thrown by Tom Cruise and Will Smith. It was all just a bit overwhelming."

It took Beckham four hours to fulfil all his media obligations at his opening news conference. He needed to be shielded at times when he waited for scheduled flights to away games, which remain a requirement for MLS clubs.

Not everything went smoothly. Two loan stints at AC Milan to further his international career went down particularly badly. But Beckham finished as a winner, lifting the MLS Cup in 2011 and 2012 - the only Englishman to win back-to-back titles.

"Having him come here and win was the beginning of something," says Klein, now LA Galaxy president.

"David made it OK for players to come to this league. Thierry Henry followed, Wayne Rooney, Zlatan, Steven Gerrard. We are not there yet but it made MLS part of the global conversation and a league that was taken seriously."

Garber calls this period "Beckham 1.0". It is impossible to quantify the difference he made but it allowed MLS to feel more confident about itself and its future. A league that had shrunk to 10 teams amid the 2001 financial turmoil was up to a healthy 19 by Beckham's final season in 2012.

David and Victoria Beckham attend an Los Angeles welcome party held in their honour. Here they are pictured with actors Tom Cruise, Katie Holmes, Jada Pinkett Smith and Will Smith.

Mistakes were still made. In 2005, Chivas became the 11th MLS franchise. Aligned with the famous Mexican side Guadalajara, the idea was to tap into the massive Hispanic population around Los Angeles. It did not work. They were sharing an out-of-town stadium in Carson with LA Galaxy and support dwindled quickly. In their final season in 2014, the average attendance slumped to 3,467. Compare that figure to the 22,000 average that watch Chivas' replacement, LAFC, play at their central location.

This season, Chicago Fire return to Soldier Field, having spent $65m (£50m) to buy themselves out of their contract with SeatGeek Stadium, some 15 miles out of the city, where they were supposed to be playing until 2036. MLS - and Garber - have long since decided soccer-specific stadiums in the heart of a city are the way forward.

It does seem more good decisions are being made than bad ones.

It is a measure of MLS' continued growth post-Beckham that 26 teams will start the 2020 campaign this weekend. More than 200 journalists attended the season launch in New York. Ian Ayre, chief executive of Nashville, says there will be more supporters at his new club's first match - against Atlanta United on Saturday - than were at Anfield for his first game after taking up a similar role with his beloved Liverpool.

There is reflected glory in the performances of Canada forward Alphonso Davies, who shone in Bayern Munich's hammering of Chelsea on Tuesday, given the 19-year-old played in MLS for Vancouver Whitecaps a couple of seasons ago.

But there are criticisms as well.

Some argue Garber, through his positions at MLS, its commercial arm Soccer United Marketing, and on the board of the United States Soccer Federation, has too much power. It is a point he denies strenuously.

A member of the 'Timbers Army' celebrates after the Portland Timbers score against Seattle Sounders. A colourful rivalry has developed between the teams since Portland's MLS entry in 2011.

The $90m (£68.7m) MLS receives in domestic TV rights pales in comparison to the $167m (£127m) NBC pay annually to beam Premier League matches into American homes.

And then there is New York City FC. Four hours after Garber spoke to the BBC in Manhattan, NYCFC reached the last eight of the Concacaf Champions League for the first time, beating Costa Rica's San Carlos 6-3 on aggregate.

The game was played in front of a couple of thousand at the Red Bull Arena, home of New York Red Bulls, NYCFC's fierce rivals. NYCFC's own home ground, the Yankee Stadium, is not in use following annual winter renovation work required before the baseball season. Major fan groups chose to boycott the match rather than make the 20-mile, hour-long trip to New Jersey from the Bronx. Plans to alter Major League Baseball's format further complicates the Yankee Stadium tenure, given NYCFC already have to play on a pitch that is right at the 110x70-yard minimum limit for MLS.

A prospective ground in Queens is the eighth to be proposed in a city notoriously short of land to build on. Speaking to NYCFC officials privately, this clearly cannot come soon enough in the club's fight for recognition in a city that hardly struggles for attractions.

Nevertheless, wider confidence was not in short supply at the 25th season launch. For Beckham and Ayre, there was a little bit of trepidation too.

Two years ago, while having a quiet coffee near his home on the Wirral, Ayre spoke about the excitement of having a blank piece of paper to begin the Nashville project with.

The intervening period has been an interesting one.

"I did say that and I meant that," says Ayre. "I didn't know what we would go through.

"When you are building a football club, you tend to zero in on the 11 players, the pitch, coach and manager. But it is everything - stadium, training ground, academy, offices. Hundreds of people. The colours, the carpets and curtains. That is part of the excitement.

"Genuinely I have been surprised at how much talking I have had to do. Nashville is a really friendly town. They want to know the story. I feel I have had to speak at about 500 events, from 10 people to 1,000.

"Also, I wasn't expecting the amount of collaboration between teams. When we were building our first-year budget, I rang other MLS CEOs and presidents and asked what they could do to help me and they literally sent me their budget. I have great respect for [Manchester United executive vice-chairman] Ed Woodward and he is a good friend, but I wouldn't have even called him about that because he would have said no."

Garber calls this weekend "Beckham 2.0", as the former United player's Inter Miami outfit get ready for their first match, at LAFC on Sunday.

Like Nashville, their intended home is still a little way off, so they will host games at Fort Lauderdale. "They have spent $120m (£92m) on a temporary stadium, which is more than many clubs' main stadiums," says Garber.

Klein knows what his friend is going through. He made the transition from player to senior club official. It is not going to be easy.

"Having the cameras on him when things are not going so well for the team is a huge challenge," he says. "David is a very competitive person and this is going to be very different. He manages his emotions publicly very well, so he is going to have to draw on those skills. I am confident he can handle it.

"I guess this is a second career for him, and he will be wanting it to be even more successful than his first."

Beckham speaks of his 'stubbornness' as Inter Miami make MLS debut